Craig Hicks, the Chapel Hill, N.C. man who has confessed to the murder of three young Muslim American students, has been defined in news stories most consistently through two attributes: his vocal atheism and his passionate support for gun rights.

Yet the #muslimlivesmatter hashtag that emerged right after the shootings and the father of two of the victims have painted a portrait of a man defined more by Islamophobia than by anything else. Islamophobia is a real and important issue, whatever role in played in Hicks’ actions. But a little history shows that the story of Muslims in America is longstanding and complex—and that they have not always been rejected nor excluded by the white, Christian majority, even in the Carolinas.

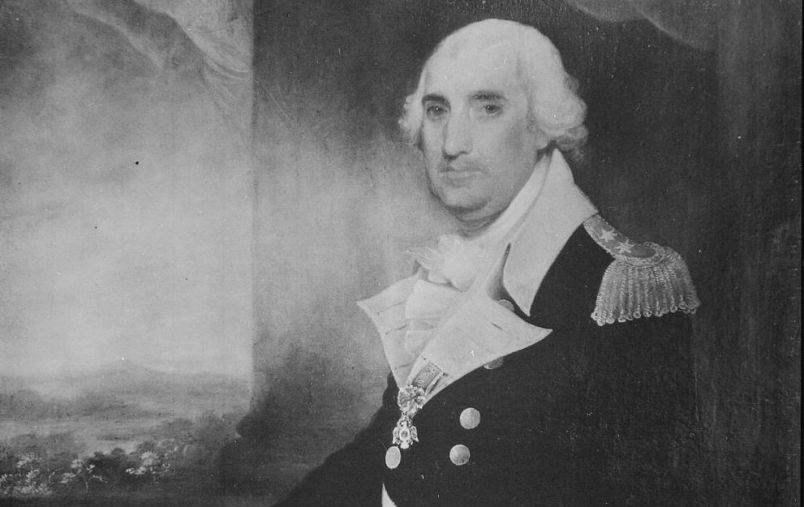

Let’s start at the beginning. By the time of the American Revolution, a sizeable Moroccan Muslim community—known as “Moors” in the language of the era—had developed in and around Charleston, South Carolina. Some of the community’s members were likely former slaves, but many others had chosen to immigrate from Morocco, with which the U.S. had a so-called “Treaty of Friendship.” Morocco, indeed, was the first African nation to recognize the new United States during the Revolution. Worried about being denied rights due to South Carolina’s system of slavery, a group of Muslim Americans petitioned the state’s courts requesting that they be recognized as white. A tribunal of judges led by prominent South Carolinian Charles Pinckney agreed with their petition, and the state legislature passed the Moors Sundry Act (1790), designating this Moroccan Muslim American community white for purposes of the law.

That law was as complicated as race in American history has always been. It allowed members of this community to be counted more fully for state population and federal representation purposes. It also gave these Muslim Americans the opportunity to vote, to serve on juries and to gain and enjoy the benefits of citizenship, even as Black Americans were largely denied those same rights.

The Revolutionary history gets broader and deeper still. The only passage in the body of the Constitution as drafted in 1787 that references religion at all is the paragraph in Article VI that makes clear that “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office.” This profoundly progressive phrase, written in an era when every other constitutional government around the world featured an official state religion, was drafted by none other than Charles Pinckney.

After the Constitution was drafted, Pinckney was tasked with taking it before the South Carolina legislature for that state’s ratification debate. During the debate, he was asked by one of the legislators about that exact Article VI paragraph, and more exactly about whether it would mean that “a Muslim could run for office in these United States?” Pinckney’s answer? “Yes, it does, and I hope to live to see it happen.” His words are inspiring, and a challenge to those who say they believe in inclusion today. How many white, Christian elected officials today would say “I hope to see more Muslim Americans in elected office” the way Charles Pinckney did?

Just as the Carolinas should not solely be defined by their history of slavery, nor should America’s relations with our Muslim communities be defined solely by Craig Hicks’ brutal act of violence. As we debate gun rights, religion, bigotry and hate crimes, we should remember that we’ve been working to live up to our highest ideals—sometimes succeeding, other times failing—for a long, long time.

UPDATE: In response to a couple of good questions, both in comments on this piece and by email, I’ve spent much of the last couple days trying to find an online source for the final exchange referenced here, between Pinckney and a SC legislator (Patrick Calhoun, per my notes). I remember distinctly reading that exchange in a transcript (at the Library of Congress) of the SC legislature debate over the Constitution, and made note of it at that time. But as I have tried to find the exchange in online/digitized transcripts in response to these good questions, I haven’t been able to do so.

So I wanted to share this update first and foremost to make that clear, and to apologize for including as part of a piece something that I had not recently sourced. Despite the immediacy of these pieces, I should only include histories or stories in them that I can source at the time of writing—that’s what I’ve normally done, here as on my daily blog, and it’s what I should have done this time. While I very much believe I read this exchange in a transcript, I can’t source it now and again apologize for including it without that confirmation.

But I also want to make sure to say this: the larger and most significant histories here are clear and fully confirmed, from the presence of this South Carolina Muslim American community and their legal petition and change in status (in which Pinckney participated), to Pinckney’s addition of the religious test clause to the Constitution and his defense of that clause as well as the Constitution overall in the SC ratification debates.

As NTodd Pritsky argues at length in this wonderful follow-up piece, both Muslim Americans and debates over including them in American society have histories that extend back to the Revolution, and it’s vital that we remember those histories.

Lead photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ben Railton is an Associate Professor of English at Fitchburg State University and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network.

Can we print out the relevant quote from the Constitution, and throw it in the faces of those who pretend that this is a “Christian country”? It won’t really change their minds, but it does kind of prove that we are in the right. I’m continuously amazed that so many RWNJs believe that there are only two Amendments to the law of the land; the Second and the Tenth. How convenient to ignore the ones you don’t like, no? Sadly, it’s not a buffet line; if you want to live under part of the Constitution, by golly, you’ll live under ALL of it.

Charles Pinckney knew why the Revolution was fought–although I’m sure he left Blacks and Indians out of his equation.

Edit: Moors Sundry Act of 1790

Not “Moors Sunday Act”

(good catch though … I am pretty well familiar with the history of the times and this is news to me)

They have also recently had some controversy at UNC about a building that was named after a former KKK leader.

And UNC and Duke about a building(s) named after slavery era figures

And ECU

http://goldsborodailynews.com/blog/2014/12/12/college-considers-removing-governor-charles-b-aycock-name-building-due-race-controversy/

Disclaimer, I went to NCSU and I’d bet you could find buildings on that campus that are also named for folks with very strong bias/deeds against race, class, gender, religion, etc., and in every state.

I’m not opposed to changing building names. Unfortunately that’s the history of the US and all mankind.

Good article.