Very few things are able to bring together the left and right in contemporary American politics, but Donald Trump’s proposal to halt all Muslim immigration (and tourism) to the United States seems to have done just that.

Every presidential contender on both sides of the aisle condemned the proposal immediately and absolutely. Jeb Bush tweeted that “Donald Trump is unhinged.” Martin O’Malley argued that the proposal “removes all doubt” that Trump “is running for President as a fascist demagogue.” Carly Fiorina called the proposal “a dangerous overreaction.” Hillary Clinton said it was “reprehensible, prejudiced, and divisive.”

New Hampshire GOP chair Jennifer Horn called the proposal “un-Republican, unconstitutional, and un-American.”

On the last note, however, American history reveals something different. Starting with the very first immigration laws in the late 19th century, and building through more than half a century of tightening restrictions into the first comprehensive national immigration policies, American officials consistently crafted immigration laws that were entirely discriminatory and exclusionary by design. The more we can remember that history, the more we can also recognize when and how it has the potential to return to our national policies and conversations—and how best to challenge it.

The first two immigration laws were the 1875 Page Act and the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, and both focused solely on creating new categories of excluded arrivals: the insane, criminals, forced Chinese laborers, and prostitutes (which in practice and on purpose came to mean “single Chinese women”) in the Page Act; and all arrivals from China (outside a few protected categories) in the Chinese Exclusion Act. These laws didn’t in any way seek to create an overarching immigration policy, establish a set of consistent rules that arrivals would follow, or achieve any such equitable purpose. They were intended solely to define particular arrivals as undesirable and create a system that would exclude those arrivals from immigrating to the United States.

A group of Chinese women thank Pearl S. Buck her for interest in their plight after she urged the House immigration committee to repeal the Chinese Exclusion Act (Washington, May 20, 1943).

Over the next 40 years, these exclusionary laws were extended and amplified in various ways. Some added new layers to the existing exclusions, such as an 1885 addendum that made it illegal for Chinese Americans to leave the country and then return (Trump now claims his ban would not do this, after his campaign initially suggested otherwise). Others folded new Asian communities into the exclusionary categories, such as the 1906 “Gentleman’s Agreement” that ended Japanese immigration or the 1917 Immigration Act that created an “Asiatic Barred Zone” of nations from whom no further immigrants would be accepted. In every case, immigration policy continued to develop as a series of widening, discriminatory exclusions.

When, in the paranoid aftermath of World War I and with white supremacist theories of Anglo-Saxon purity reaching a zenith, Congress decided to enact for the first time a much more comprehensive immigration policy, it did so by overtly extending these exclusionary goals to many more nations. The 1921 and 1924 Quota Acts were designed precisely to lessen immigration by limiting arrivals from those nations and cultures deemed least desirable in white supremacist fantasies.

One of the 1924 bill’s strongest supporters, South Carolina Sen. Ellison DuRant Smith, argued on the Senate floor, “It seems to me that the point of this measure … is that the time has arrived when we should shut the door … Thank God we have in America perhaps the largest percentage of any country in the world of the pure, unadulterated Anglo-Saxon stock … and it is for the preservation of that splendid stock that has characterized us that I would make this not an asylum for the oppressed of all countries, but a country to assimilate and perfect that splendid type of manhood.”

This was the perspective that created our first half-century of immigration law and policy, the perspective that would subsequently apply such white supremacist and xenophobic attitudes and arguments to both Japanese Americans and shiploads of Jewish refugees during World War II. Those of us who would condemn in absolute terms such attitudes and arguments must at the same time remember that they are all too American in the longstanding and significant role they’ve played in our histories of immigration and diversity.

The Immigration Act of 1965 reversed the national and ethnic discriminations in our policies, but the debate over that law, and the many subsequent and ongoing debates over diversity and multiculturalism in America, reflect how fully the exclusionary perspective has endured. In a moment when it has returned in full force, given voice by a figure cut from precisely the same cloth as the DuRant Smiths of our past, we would do well to remember those histories, so we can better challenge and resist them in the present.

Ben Railton is an Associate Professor of English and American Studies at Fitchburg State University and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network.

Actually, the early immigration laws of the US were designed to provide the most benefit to America, not to the immigrants.

Basically, the laws were intended to exclude what were (at that time) considered undesirable elements from new immigrants, again to improve America, not the immigrants .

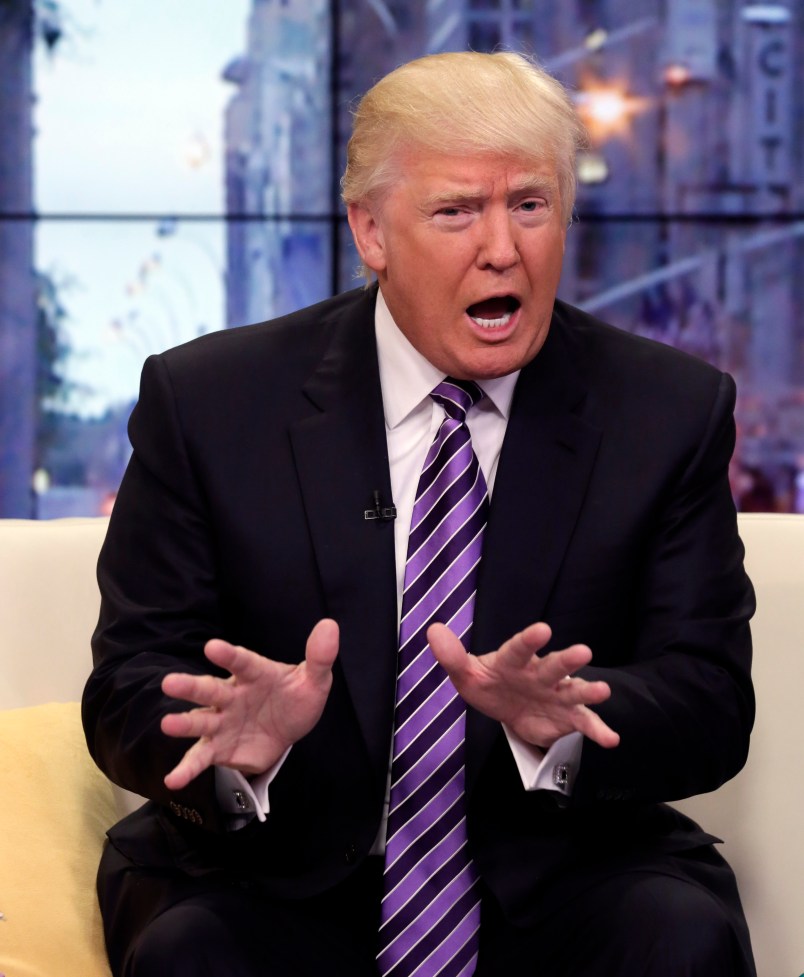

Donald Trump is the

walking, talkingstrutting, yelling, bigoted embodiment of everything bin Laden hoped to achieve on 9/11/01.As Ted Cruz quietly distances himself without openly condemning, he must be licking his chops at the prospect of picking up Trump’s supporters.

Cruz, the opportunist, is waiting on the sidelines to pick up the pieces if/when Trump implodes!

Yes, we were improving America by codifying our racism. Got it.