This article is adapted from The Rebels: Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and the Struggle for a New American Politics by Joshua Green.

If you were to go looking for one event that shaped recent American politics more than any other — fueling the anger and contention that now feels endemic, eroding the nation’s faith in its leaders, and elevating radical alternatives in their place — the 2008 financial crisis would be a strong contender. It was the point at which America broke down, political consensus went up in smoke, and long-standing assumptions about how society should be organized, and for whose benefit, came under scrutiny.

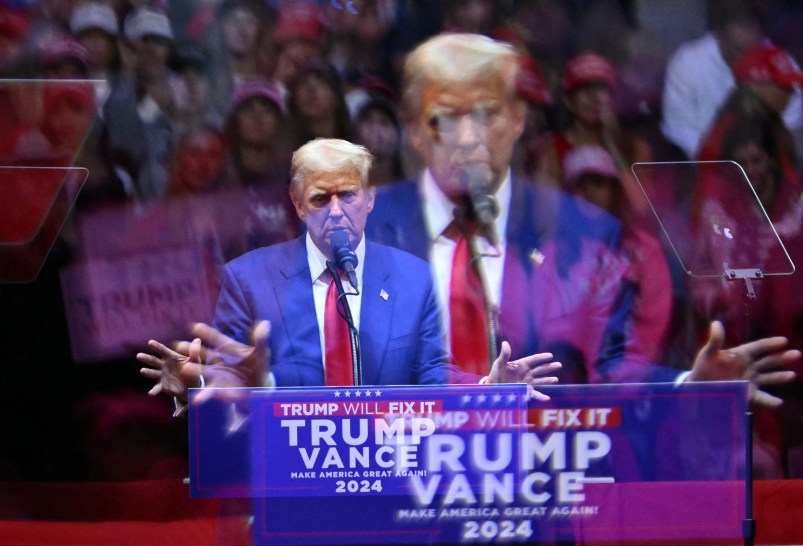

The clearest expression of this popular discontent came, of course, on the political right with the election of Donald Trump. But the 2008 financial crisis also produced a new strain of populism on the left. Or, rather, it revived an old strain of economic populism that would have been familiar to Democrats of the New Deal era but had fallen dormant in the decades before the crisis, when enthusiasm for regulating financial markets and suspicion of Wall Street banks was pushed to the margins. The crash brought it roaring back and, in so doing, raised a series of bedrock questions: How had the Democratic Party, traditionally the champion of workers, come to identify so strongly with Wall Street? Who made this happen and why? What could be done to return the party to its working-class roots? And who should lead the transition to a new era?

There is a backstory that illuminates the Democratic Party’s embrace of finance in the years leading up to the crash — a story that begins in 1978. At the time, Democrats were still reliable partisans of the New Deal, but the steady economic progress of the American middle class was coming to a turbulent end. Jimmy Carter was president. He was struggling, without much success, to manage an economy buffeted by inflation, oil shocks and recessions — problems for which his party had no answers. A conservative countermovement of business groups and Republican politicians was beginning to gather force. One of history’s critical inflection points arrived that fall, when Wall Street made its first deep incursion into the Democratic Party in a way that would have lasting significance, although it passed mostly unnoticed at the time.

The great irony of this early conquest is that it began with Carter’s ambitious attempt to change the tax code to favor workers at the direct expense of Wall Street investors. Instead, Carter and his fellow reformers suffered a defeat so thorough that the financial lobby not only got to preserve its favorable tax treatment, but was able, with Democratic help, to rewrite the rules of the economy in a way that gave Wall Street an enduring structural advantage at the expense of the middle class — the opposite of what Carter had set out to do.

As much as anything, the story of this fight and how Carter lost it captures the tectonic shift that took place in America as the New Deal era was ending and a new one was being born. It set the party on a path that would transform it into something Democrats of an earlier generation would hardly recognize.

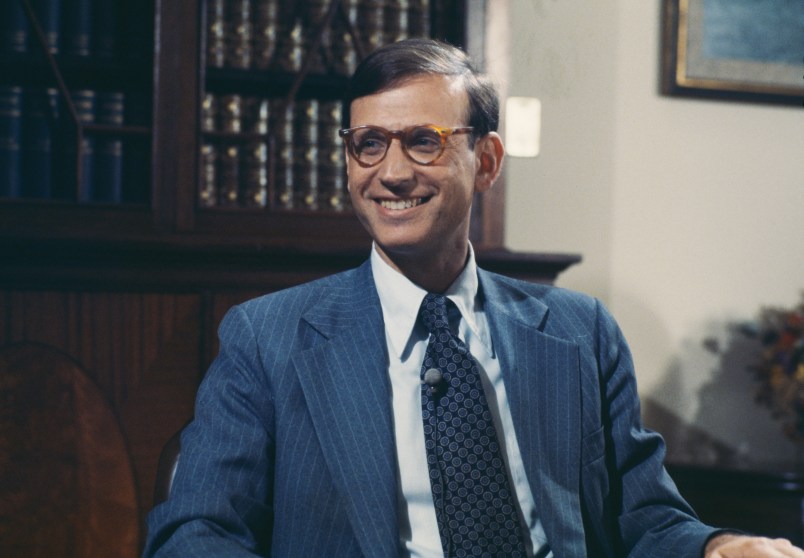

It is October 14, 1978. Jimmy Carter is sitting in the Oval Office about to make what he knows will be one of the pivotal decisions of his still-young presidency. He is deeply unhappy. The economy is souring. Inflation has picked up again. The midterm election is three weeks away. And it is now clear that his own party’s congressional leaders have betrayed him on a matter he considers to be of great moral importance and in a manner designed to humiliate him personally. Across from him sits a young aide in horn-rimmed glasses, Stuart Eizenstat, who is furiously scribbling Carter’s complaints onto a yellow legal pad. If you want to locate the moment when the Democratic Party first turned toward Wall Street, when the party of the New Deal quietly switched tracks and started steaming off in a different direction, it’s right now, and its initial rationale is laid out in the tale of futility that Eizenstat is recording in his yellow pads.

Carter’s charmed run for the presidency was propelled by the strength of his personal story: Farmer, governor, Southerner, born-again Christian, his rectitude and modesty — the very image of him in blue jeans and work shirts — was an antidote to the national nightmare of Nixon’s Washington. Carter was a populist. The societal rot that produced Watergate, he told voters, grew out of a corrupted value system that powerful business interests had enshrined in the federal tax code — “a disgrace to the human race” and “a welfare program for the rich” that warped every aspect of American life. As he traveled the country campaigning, he’d catalogue its grotesque injustices: deductions for yachts, sports tickets, country clubs and first-class airfare; preferential treatment for capital gains so investors and the idle rich paid less than ordinary workers. At the same time, he’d note, the middle-class tax burden was rising as inflation pushed those workers into higher brackets.

Carter had a favorite illustration that gave vivid dimension to his message that inequality was rampant: the deductibility of “the three-martini lunch.” As a populist symbol of elite self-dealing, it was hard to beat. The thought of well-heeled businessmen and lobbyists getting plastered in the middle of the day — at taxpayers’ expense! — was infuriating to voters, especially in the wake of the 1974-75 recession. “When a business executive can charge off a $55 luncheon on a tax return and a truck driver cannot deduct his $1.50 sandwich,” Carter would say, “then we need basic tax reform.”

That his attack elicited howls from its targets only added to its broad popular vitality. “You’re taught there’s virtue in working hard,” one banker griped to the New York Times. “So you work hard, and just when you get to where you’re about to enjoy some of the reward, you’re hated and punished.” Another complained: “Who are these people, a bunch of Bolsheviks? It took me all my life to get into the eating class and now they want to take it away.” The National Restaurant Association briefly considered launching a march on Washington but seemed to sense that saving the businessman’s lunch deduction wouldn’t quite measure up, in the public’s estimation, to causes such as advancing civil rights and ending the Vietnam War that had spurred earlier Washington marches. Finding the most fatuous example of Wall Street outrage at Carter and crafting a story around it became a kind of sport among national media outlets. “We’re in a hyper-tense, high-pressure business,” a Wall Street stockbroker huffed to the New York Times, “and if it weren’t for these lunches, some of these people would be dead.”

Along with his diagnosis of what ailed the country, Carter had offered a solution: zero out the tax code, wipe the slate clean, and start anew. He’d tax capital gains at the same rate as income to put workers back on equal footing with their bosses. He’d eliminate the obscene loopholes through which the middle class subsidized the extravagances of the wealthy. Through determined effort, he would impose his own values — his simple Baptist decency — on the travesty of the federal tax code, ushering it through the Democratic Congress from whence it would emerge, reborn. To Carter, questions of dollars and cents were secondary to the moral dimension of the problem. When informed that killing the business entertainment deduction for the three-martini lunch wouldn’t bring in much government revenue, he shot back, “I don’t care whether it brings in revenue or not — it’s wrong.”

Tax reform was front and center when Carter had stood before the bunting and stage lights in Madison Square Garden to accept his party’s nomination at the 1976 Democratic National Convention. “The powerful always manage to find and occupy niches of special influence and privilege, and an unfair tax structure serves their needs,” he declared. “Unholy, self-perpetuating alliances have been formed between money and politics, and the average citizen has been held at arm’s length.” He continued, “It is time for a complete overhaul of our income tax system. I still tell you: It’s a disgrace to the human race. All my life I have heard promises about tax reform, but it never quite happens. With your help, we’re finally gonna make it happen.” Then, with a broad smile, he shouted, “You can depend on it!”

Now, Carter is no longer smiling. As he sits with Eizenstat venting his frustrations, his grand plan to reform the tax code has just collapsed and divided his own administration, some of whose members have been trying to influence him by sending him private memos quoting his campaign promises to remedy the tax code in favor of working people. His party is likewise divided, and so is the president himself. Carter doesn’t know what to do. He laments to his aide, “Tax reform is so screwed up.”

He’s right about this, and he’s also right to sense that his decision will be a turning point in his presidency because the powerful business interests he campaigned against are on the verge of achieving a victory that Carter has the power to stop. What he doesn’t know is that it will also be an inflection point in the history of the Democratic Party, one that Eizenstat and other administration officials will come to rue even before they leave the White House. Decades later, Eizenstat will dig up his old yellow note pads and wish he’d counseled Carter differently at the time.

Carter had, in fact, already made an honest stab at reform. At the beginning of his presidency, things even looked auspicious. To spearhead the effort, Carter had lured to the Treasury a superstar named Laurence Woodworth, the longtime director of Congress’s professional tax policy staff, who was trusted and admired by both parties and, though forbidden as a civil servant from expressing political views, was known among reformers to secretly be one of their own. Woodworth liked to dazzle congressmen and reporters by scrawling complicated figures on his chalkboard and then explaining them in plain English; in turn, they lionized him as “a walking encyclopedia of tax law” and Carter’s secret weapon on reform.

But things had quickly gone awry. Upon taking office, Carter’s advisers had decided that the economy looked weak and prevailed on him to delay tax reform and first pursue a stimulus, which had bogged down in Congress and finally been dropped. Then rising oil prices necessitated an energy bill. That too got stuck in Congress and further damaged the deteriorating relations between the White House and Democrats on Capitol Hill.

The Carter administration’s inability to steady the faltering economy was a key reason tax reform failed. It left an opening for someone who did have a solution — or at least claimed to. Carter never saw him coming.

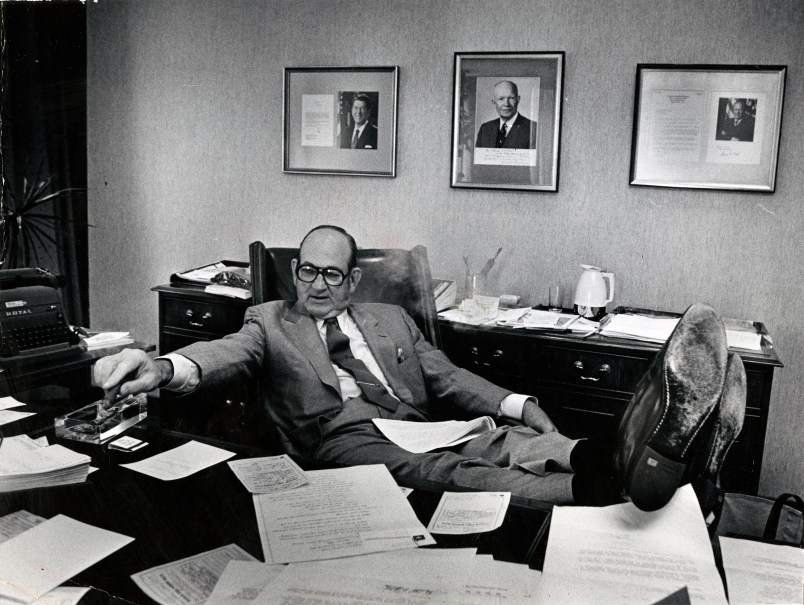

Charls Walker was the living, breathing, cigar-smoking embodiment of a three-martini lunch: a jowly, pinstriped Washington super-lobbyist and friend to all in power, who rode a black limousine between Capitol Hill and Sans Souci, the French restaurant a block from the White House where he held court over glasses of white wine and filets of sole. Raised poor in north-central Texas, Walker (whose mother dropped the “e” from his name in a failed effort to ensure he wouldn’t be called “Charlie”) rose to become, in succession, a Ph.D. economist at the Fed, fixer for the American Bankers Association, and deputy secretary of Nixon’s Treasury, a position he left in 1973, sensing greater profit and opportunity on the outside. With his rough-hewn charm and gravelly Texas twang, Walker founded the capitol’s hottest lobbying shop and convinced big business generally, and Wall Street in particular, that he could reverse a decade-long losing streak in Washington that Carter’s reforms threatened to extend.

An astute anthropologist of power, Walker had witnessed from his perch at the Treasury how Ralph Nader’s army of public interest lobbyists skillfully cultivated grassroots pressure campaigns that bypassed the committee chairmen, who were traditionally the power brokers, and targeted junior members, often in their home districts rather than Washington, D.C. Walker further recognized, as Nader had, that party rules had shifted after Watergate, opening a path to outsiders like Carter and fragmenting power in Congress in a way that strengthened the rank and file at the expense of the chairmen. Nader’s Raiders exploited this insight to secure a succession of legislative and regulatory victories, several of them in the realm of tax law.

Soon after Carter launched his presidential bid, Walker took over a sleepy financial industry trade group called the American Council on Capital Gains and Estate Taxation and rebranded it as the more exalted-sounding “American Council on Capital Formation,” a euphemism for the aggressive accumulation of wealth. Walker began pushing the idea that the economy’s productivity crisis could be solved if the government changed the way it induced business investment. Since the New Deal, the preferred method had been the investment tax credit, which rewarded companies for building factories. This generally satisfied labor interests, since factories produce jobs. The major business lobbies like the Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers liked the investment tax credit because many of their members were large industrial corporations. Carter’s plan to eliminate the capital gains preference didn’t threaten them.

But it terrified Wall Street. Walker’s project was to pull off a feat of legislative legerdemain by persuading lawmakers that the solution to U.S. economic malaise lay in shifting the government’s focus to encouraging capital formation — a move that would, its backers insisted, revitalize the supply side of the economy by spurring investment, unleashing entrepreneurial energies and turbocharging productivity. In practical terms, this meant preserving the biggest giveaway to investors in the tax code: the capital gains preference.

It wouldn’t look good to run a campaign to preserve a loophole for the wealthiest Americans from the backseat of a limousine. So Walker took a page from the Naderites. Working through local business groups and the newly formed Business Roundtable, which he’d helped launch, Walker arranged for the gospel of capital formation to be spread among the members of Congress and the press. No one was overlooked. Although he had no idea Walker was behind it, Rep. Abner Mikva of Illinois, one of the most liberal Democrats in Congress, and later Barack Obama’s mentor, described the uncanny experience of being proselytized to by Walker’s forces. “I got phone calls from several people back in my district who had been supporters of mine, and contributors,” he recalled. “People who seldom asked for anything. Progressive members of brokerage houses. Public-spirited bankers. First, they asked if we could have lunch. There was no arm-twisting. They were polite, thoughtful, erudite. They had their facts. We have to do something for the economy; look at the low rate of savings. The letters I got were not mass mailings. They were intelligent letters from people who knew me well. Now, obviously, somebody back in Washington was masterminding this, but I’m sure that some of it did sway me.” The reason the pitch was so effective, Mikva explained, was its careful framing: “On an issue like capital formation, where you only hear from business, it isn’t something for me and nothing for you; it’s something for me, and this doesn’t concern you.”

Throughout Carter’s first year in office, as tax reform was repeatedly delayed, the context in which Congress would eventually consider it was undergoing a full-scale change few were aware was even happening. “Within a relatively short period of time,” Walker bragged, “‘capital formation’ has entered the lexicon of ‘good’ words — not quite equal to ‘home’ and ‘mother,’ but still a public policy few would disagree with.”

By the time Carter finally turned his attention to his long overdue tax bill in late 1977, the economic and political landscape had shifted. Inflation was climbing toward double digits. Discontent was brewing. The public’s focus shifted from tax reform to tax relief. The White House domestic policy staff and Woodworth’s Treasury team kept pushing for sweeping change centered around the elimination of the capital gains preference. But skeptics in the administration worried the economy might be too fragile for the shock of major reform. In November, Carter’s Treasury Secretary Michael Blumenthal told Congress that in light of the weakening economy, the long-awaited tax bill would focus on tax relief and stimulus — signaling that comprehensive reform was in trouble and Carter was retreating.

Things quickly devolved from there.

Alerted by allies in Congress that support for reform was crumbling, Carter held a news conference to announce an indefinite “time out” for his plan. Then, in December, Woodworth, whom the White House was counting on to sweet talk the old bulls in Congress, dropped dead of a stroke while attending a tax conference in Virginia. Carter attempted a reboot by finally introducing a watered-down tax bill in his 1978 State of the Union address that aimed to appease all sides by cutting corporate taxes, making permanent the investment tax credit, and sacrificing the bulk of his capital gains reforms. But he found little support, in Congress or anywhere else. Walker’s Wall Street contingent was privately stunned: They’d won the battle before the first shot was even fired. And Walker still had an army at the ready. “They were braced for an attack,” one congressional staffer explained. “When the attack never came, they decided to invade!”

At Walker’s urging, several members of Congress, having fought off a capital gains increase, now turned around and started pushing for a tax cut. Wall Street brokerage houses led by Merrill Lynch and E.F. Hutton bombarded investors with mail telling them of the riches they stood to gain if rates were reduced. As the insurrection mounted over the spring, Ullman stopped work on the tax bill. But the momentum against Carter didn’t slow. On June 6th, California voters overwhelmingly passed the landmark ballot initiative Proposition 13, which slashed property taxes, made the cover of Time, and sparked a nationwide tax revolt. Dozens of anti-tax measures popped up in states across the country, helping shift the national mood in a more conservative direction and prefiguring the rise of Ronald Reagan.

In Washington, Carter’s reformers were overrun like Custer’s cavalry. Yet his humiliation wasn’t finished. In a remarkable feat of legislative jujitsu, Walker’s congressional allies prevailed upon Ullman to swap out the president’s tax reform bill for one of their own that, on every major front, was a repudiation of Carter’s principles. Instead of raising the capital gains rate to match income tax rates, the new bill slashed it, while adding a blizzard of new shelters and exemptions for the wealthy. Practically no one in Congress wanted to go against the national mood and block a bill that cut taxes. In effect, Walker’s forces harnessed middle-class rage over inflation-driven tax increases like those that prompted Proposition 13 and redirected that rage to support a windfall tax relief for the rich. Inside the citadels of the right, the mood was triumphant. “Any resemblance between this bill and President Carter’s original tax message is purely coincidental,” an internal analysis by the conservative Heritage Foundation crowed.

When the bill got to the Senate, Russell Long had no interest in rescuing Carter. Instead, he pushed for an even larger capital gains cut. With the midterm elections looming, Democrats were as eager as Republicans to show they were doing something for the economy. Only 10 senators voted against Long’s bill. Through it all, Carter watched dejectedly from the White House. “I think the story may well be that not only did we send up a tax package that misread the mood of Congress,” one of Eizenstat’s deputies wrote to him in a private memo, “but upon being rebuffed, we retired from the field and became eunuchs.”

By October 14th, as Carter and Eizenstat waited unhappily in the West Wing, House and Senate negotiators hashed out a joint bill in a marathon overnight session. The full measure of Carter’s failure now became clear. One of his defeated soldiers, Rep. Pete Stark of California, used his allotted floor time to read into the Congressional Record a snippet of doggerel he’d composed to mark the bitter occasion and make one final plea to his president:

The speaker had sold all the Liberals a Bill,

And Good Chairman Ullman had swallowed the Pill.

With loopholes for dry holes,

And tax breaks for wine,

The deeds of the lobbyists,

Were almost a crime.

They took care of the heirs,

And built up the shelters,

But for the poor folks,

Russell gave us no helpers.

The rich will have Christmas with ill-gotten gains,

While others pay taxes with annual pains.

But Scrolling the people is Washington’s credo,

Now what we need, Tiny Jim, is a veto!!!

And right there, Stark put his finger on the only move Carter had left. Sitting in the West Wing with his yellow note pad, Eizenstat wonders if he has the nerve. This is the decision Jimmy Carter is about to make: whether or not to veto the tax bill.

That night, Eizenstat goes home and composes a lacerating assessment of the tax bill now headed to Carter’s desk, bluntly laying out the extent of the administration’s failure and the consequences of Carter’s options.

“The unpleasant facts we have to face squarely are: the House passed a bad bill, the Senate passed a bad bill, and the final bill is not a good bill,” Eizenstat writes in a private memo to Carter. “It contains large tax reductions for the wealthiest citizens in our country and small reductions for average working people. It would constitute a setback for tax reform.” Incredibly, Eizenstat adds, “The middle class will actually bear a slightly larger share of the overall tax burden under this bill than under present law…they will bear net tax increases.” He goes on, “The bill does not achieve your attempt to achieve greater fairness, progressivity, and simplicity and moves in the opposite direction.”

On the other hand, it does include a $20 billion tax cut. The midterm elections are three weeks away and Democrats want something to run on. Denying them this could imperil Carter’s strained relations on the Hill and fatally weaken his public image. “A veto now,” Eizenstat warns, “could change the whole tone of the press coverage of the Administration’s first two years.”

What Carter’s advisers agree on is that he needs to make up his mind quickly so Democrats have time to react before Election Day. Instead, Carter waits until the day before the election, November 6th, and only then, without fanfare and in the privacy of his office, does he pick up his pen and sign into law a measure that in many respects marks the end of the New Deal era in Democratic political history, and the start of a new one.

Carter’s decision to sign a bill undermining his own publicly declared principles not only marked a crossroads in his drifting presidency but helped alter the correlation of forces in Democratic politics for a generation to come.

From the end of World War II until the late 1970s, the Democratic Party was a coalition of interest groups in which labor was the senior partner. Unions supplied the organizing muscle for the party’s electoral strategy, and improving workers’ wages and living standards was the party’s chief domestic concern. Democrats emphasized collective bargaining, tight labor markets, and expansionary fiscal policy, which produced a decades-long record of middle-class prosperity: real income for the median family doubled between 1947 and 1973. Relatively stable income distribution between workers and their bosses also produced labor harmony. Historians dubbed this epoch “The Great Compression.”

The 1973 oil shock and the recession that followed brought it crashing down. It’s easy to share a growing pie — but as productivity fell, inflation spun out of control, labor weakened, and U.S. manufacturers faced stiffer competition from abroad, economic growth slowed and the old political alignment came apart. It was Carter’s misfortune to govern during this period, made worse by the fact that he lacked political skill and his advisers didn’t know how to generate long-run economic growth in the face of seemingly intractable problems. Carter got rolled in the 1978 tax reform fight because his supply-side opponents, aided by Walker’s deft salesmanship, convinced people that they did know how to fix the economy. As one historian of the era put it, “Carter and his advisers vacated this intellectual space, which was filled by radical new solutions, capital gains reduction and supply-side tax cuts, [replacing] the assumptions that capital and labor should prosper together with an ethic claiming that the promotion of capital will eventually benefit labor — trading factories for finance.”

Troubled by growing inequality, Carter had set out to rebalance in favor of the middle class the rewards government allots through the tax code. What he ended up with was a law that further empowered the very forces whose influence he sought to curb. Not only did the Revenue Act of 1978 cut corporate and capital gains taxes — redirecting investment from factories and equipment to financial instruments — but it also established the 401(k) retirement account, which channeled trillions of dollars more directly into the markets and undermined a pillar of middle-class security by eliminating employers’ obligation to provide pensions that ensured workers a stable retirement. If you go back to the Great Depression and trace the share of U.S. wealth held by the richest one percent of Americans, it falls steadily until 1978, whereupon it reverses and begins a steep ascent that continues to this day:

The law’s lasting impact on Democratic politics was that it ended a set of arrangements and a way of thinking about the economy that had held for four decades and replaced them with a new arrangement. Without quite realizing it or intending for it to happen, Carter’s signing the Revenue Act marked the beginning of the ascendance of finance capitalism as the major influence on Democratic policymaking. As organized labor declined, Wall Street assumed the role of senior partner in the party coalition. Democratic politicians, in turn, began emphasizing different priorities than during the Great Compression: fiscal austerity, soft labor markets, free trade with low-wage countries, and the further weakening of private-sector unions.

When historians analyze party takeovers, they tend to focus on big changes at the top and how those filtered down — how Donald Trump’s hijacking of the GOP, for instance, reversed the party’s positions on immigration and trade. Wall Street’s takeover of the Democratic Party wasn’t like that. It was gradual. It began at the bottom and filtered up. No singular charismatic figure or nefarious master plan was behind it, and even people like Charlie Walker who ushered the process along didn’t think of themselves as being involved in a grand ideological project to reshape the American political economy. But the takeover was no less real because of it.

Beginning in 1978, Democrats, over Jimmy Carter’s objection, embraced Wall Street’s idea that encouraging “capital formation” was the surest way to revive the moribund economy and set America on a path to broad prosperity. The neoliberal era that spanned the next four decades put this new faith at its center, relying upon market forces rather than the government to set the party’s course. Its dominance was so thorough that dissenting voices were eclipsed or ignored, and its Wall Street proponents didn’t just guide policy but also financed campaigns and assumed top positions in government. In both Democratic and Republican administrations the prevailing view among the people running the White House, the Federal Reserve, and the Treasury was that prioritizing inflation control, deficit reduction and financial deregulation should take precedence over social objectives such as promoting full employment and addressing income and wealth inequality.

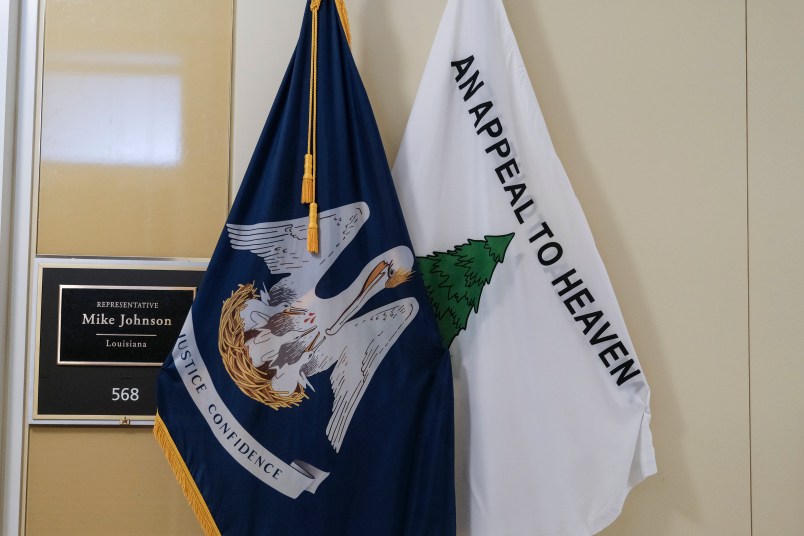

It took the collapse of the U.S. economy in 2008 and the social upheaval that followed for this way of thinking to lose its grip on American political and intellectual life. When the populist challenge arrived, it came from politicians well outside the Democratic mainstream because that’s the only place it could have come from.

This article is adapted from The Rebels: Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and the Struggle for a New American Politics by Joshua Green.

Thank you for this excellent treatise on President Carter’s backfired efforts at tax reform. If I’d ever known about them, I’d long forgotten (though, to be fair, I was only 15 when he was elected).

About the only thing I think I can add is that from a social issue perspective, 1978 was ground zero for the National Conservative Political Action Committee (NCPAC, and pronounced “NICK-pak”) founded by the usual suspects and presaged Ronald Saint Reagan’s 1980 electoral college landslide.

Between them and what, the next year, would become former segregationist Jerry Falwell’s so-called Moral Majority, one can easily see the two halves of the “economic anxiety” and Christianist Nationalist wings of the Republican’t Party w/ which we’re still dealing today.

These events were a step toward where we are now, but I can’t agree it led directly to today’s mess. Citizens United sealed the deal and accelerated the whole mess. It was the framework to building the separation of society and the .01% that removed the opportunities for today’s generations.

I’m old, I remember the Medicare recipients chasing Sen. Dan Rostenkowski down the snowbanked street, threatening bodily harm with their crutches in 1987. He went back and did a somewhat better thing.

“Beginning in 1978, Democrats, over Jimmy Carter’s objection, embraced Wall Street’s idea that encouraging “capital formation” was the surest way to revive the moribund economy and set America on a path to broad prosperity.”

Yes, but no small part in this transition is that the revolving door of politics/private sector now made many Dems going through that door much, much richer; and they really liked that. Their personal prosperity (to hell with broad prosperity) helped drive them further to the top 5% where they wanted to be. To this day most productivity gains since 1978 have not gone to workers in wages (see flat wage rates) but to capital as wealth. Nobody is very surprised. The resulting wealth gap is skewing our politics badly.

This article contains many useful facts about a major inflection point in American politics.

Its political history is, however, complete trash.

Carter did not run as a populist. He ran as a southern businessman, a "different kind of Democrat. A southern who was not a racist, who understood the motives of populism, embraced them, but was not defined by them.

Corporatist control of the Democratic Party did not begin as a reaction to Carter and populism. The Democratic coalition was a weird amalgamation of southern racists and northern liberals. The racists accepted the New Deal because it was good for the economic interests of their poorer voters. The liberals lived for the New Deal and accepted Wall Street money because they knew the New Deal was good for the economy. (This amalgamation was roughly analogous to the pre-Trump Republicans with their Wall Street financing and their racist voting strength.)

Wall Street dominated the Democratic Party for the quarter century before Carter even as it preferred the GOP. The conservative wing of the party got its Vietnam War (and Cold-War spending as well) and the rest of the party got guns-and-butter stimulus. Which Wall Street liked as well.

“Capital formation” was the rallying cry of conservative economics going back to Calvin Coolidge. The truth is: Government policies never affect capital formation; tax policies never affect business investment.

Businesses put money into capital investment because people are buying more of their product than they can produce. Period.

I would like to thank TPM for giving me this peek at this book. You saved me the cost of purchasing it.

My memory of Carter’s presidency are influenced by my proximity to organized labor. They had, of course supported Carter, but at some point their views changed from support to the belief Carter lacked leadership to succeed. There definitely was disappointment.

When Reagan won in 1980, labor believed, correctly, that progress and success in growth and power of organized labor was over.

My recollections are from conversations among labor union leaders, not from a position I held.

Another loss from Carter’s loss was support of public education.