BOISE, Idaho (AP) — In Facebook posts written before he vanished from his military base in Afghanistan, Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl spoke of his frustration with the world and his desire to change the status quo.

He criticized unnamed military commanders and government leaders and mused about whether it was the place of the artist, the soldier or the general to stop violence and “change the minds of fools.”

In his personal writings, he seemed to focus his frustrations on himself and his struggle to maintain his mental stability.

Together, the writings paint a portrait of a young man who was dealing with two conflicts — one fought with bullets and bombs outside his compound, the other fought within himself.

Bergdahl’s Facebook page was found by The Associated Press Wednesday, and it was suspended by Facebook for a violation of its terms a short time later. Bergdahl opened the page under the name “Wandering Monk.” His last post was made May 22, 2009, a few weeks before he was taken prisoner.

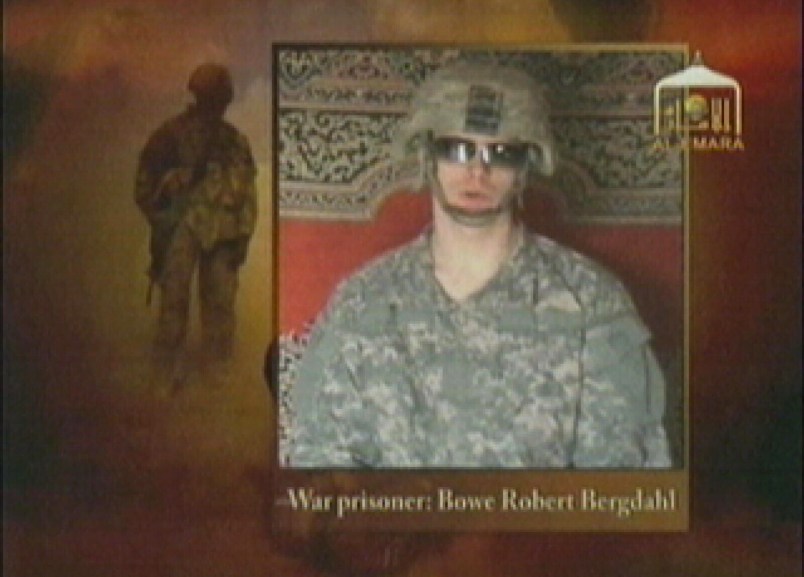

Bergdahl, the only U.S. soldier held captive in Afghanistan, was recently released after five years as a prisoner of the Taliban. In exchange, the U.S. released five detainees from a detention center in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The circumstances surrounding the prisoner swap and Bergdahl’s capture in 2009 have raised a national debate, with Bergdahl’s supporters and friends joyous at his rescue, and some members of Congress — and some of his own platoon members — calling him a deserter.

Mary Robinson, a Facebook friend of Bergdahl, worked with him in a massage center and tea house near his home when Bergdahl was in high school. Robinson said she didn’t know why Bergdahl chose the Wandering Monk moniker.

“He was really, really grounded. He was curious. He wasn’t one who was partying as some kids do,” Robinson said while verifying it was Bergdahl’s Facebook page. “He was going over there with all the good intentions of serving his country.”

In his May 22 post, Bergdahl described what was supposed to be an 8-hour mission in the mountains of Afghanistan. The mission instead took five days after vehicles in the convoy became disabled from roadside bombs. The group had to camp outside a small mountain town, Bergdahl wrote in the frequently misspelled posting.

When the convoy finally started back to the base, they traveled along a creek bed in a long, deep valley lined with trees and boulders. Again one of the vehicles hit an improvised explosive device, according to Bergdahl’s post, and as the soldiers tried to hook the vehicle to a tow strap they began taking fire from people hidden on the hillside.

Enemy combatants “begain to splatter bullets on us, and all around us, the gunners where only able to see a few of them, and so where firing blindly the rest of the time, up into the trees and rocks,” Bergdahl wrote.

When a machine gun mounted on the truck carrying Bergdahl quit working, he had to hand over his own weapon to the gunner.

“I sat there and watched, there was nothing else i was allowed to do,” he wrote.

No one was killed in the encounter, but Bergdahl was frustrated by the danger and the situation.

“Because command where too stupid to make up there minds of what to do, we where left to sit out in the middle of no where with no sopport to come till late mourning the next day. … But Afghanistan mountains are really beautiful!” he wrote.

About two and half weeks after his last Facebook post, Bergdahl sent a partially coded email to Kim Harrison, a longtime friend, suggesting he had concerns about his privacy and so couldn’t share his plans.

Harrison shared that email and other personal writings of Bergdahl with the Washington Post (http://wapo.st/1l2jlNI ) because she said she’s concerned about the way he’s being portrayed, as a calculating deserter.

Two weeks after the coded email, Bergdahl vanished from his base. A box containing his journal, laptop computer and other items arrived at Harrison’s home several days after that.

The writings she found were more disturbing than the ones Bergdahl put on Facebook.

“It’s about my concern for Bowe and others and that’s why I talked,” she told the AP. “I’m not talking anymore.”

Bergdahl’s journal appeared to detail his struggle to maintain his mental stability during basic training and his deployment to Afghanistan.

“I’m worried,” he wrote in an entry before deployment. “The lcoser I get to ship day, the calmer the voices are. I’m reverting. I’m getting colder. My feelings are being flushed with the frozen logic and the training, all the unfeeling cold judgment of the darkness.”

Later, he wrote, “I will not lose this mind, this world I have deep inside. I will not lose this passion of beauty.”

The writings weren’t the first time Bergdahl’s friends were worried about his emotional health, Harrison told the Post. In 2006, he left the U.S. Coast Guard after 26 days in basic training in an “uncharacterized discharge,” according to Coast Guard records, the Post reported. Harrison said it was for psychological reasons.

But when he joined the Army in 2008, the military was dealing with wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and was regularly issuing waivers that allowed people with criminal records, health conditions and other problems to enlist. The military declined to say whether Bergdahl was given such a waiver.

___

Associated Press researchers Rhonda Shafner and Susan James contributed to this report.