I see this morning President Trump isn’t sure why the Civil War happened. In line with your standard Trumpian militant ignorance, he assumes that since he isn’t sure what happened that “people” aren’t sure either. In fact, they haven’t even asked the question. “People don’t ask that question, but why was there the Civil War? Why could that one not have been worked out?” As I’ve noted, President Trump is not only wildly ignorant. But, utterly unaware of the scope of his ignorance, he assumes everyone else is as ignorant as he is and frequently preens with new learnings that either everyone knew or in other cases are just completely wrong.

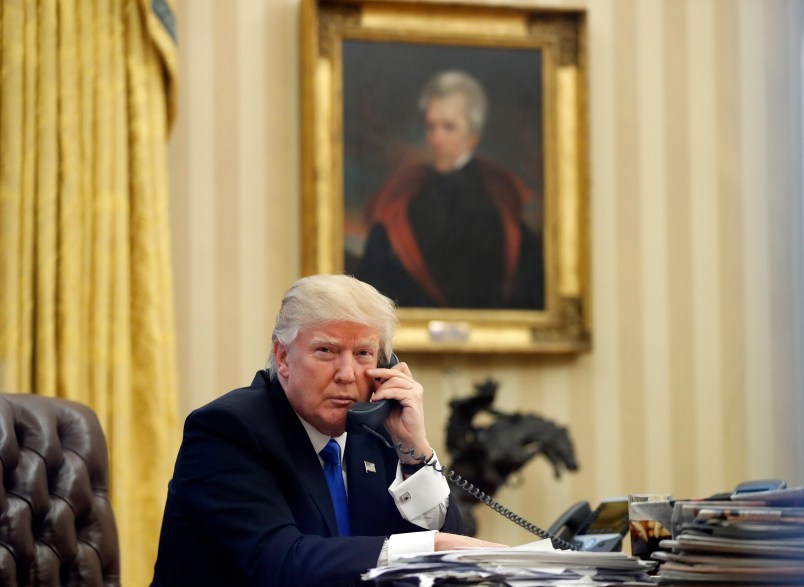

But I want to zero in on Trump’s comments about Andrew Jackson and the Civil War. Under Steve Bannon’s tutelage, Trump has embraced Jackson as the “nationalist” progenitor of his presidency. But here he shows he doesn’t know the first thing about Jackson. And the ignorance is of more than historians’ concern.

Here’s what Trump said in an interview with Salena Zito.

“I mean had Andrew Jackson been a little bit later you wouldn’t have had the Civil War. He was a very tough person, but he had a big heart. He was really angry that he saw what was happening with regard to the Civil War, he said, ‘There’s no reason for this.'”

Pundits are noting that Jackson left the White House in 1837 and died in 1845, 24 and 16 years before the outbreak of the Civil War. But the Civil War actually wasn’t so far from Jackson’s own time, indeed during the years of his own presidency. The final months of Jackson’s first term as president saw what historians refer to as the Nullification Crisis. In critical ways, it was a dry run for the Civil War. The notional trigger of the crisis was a tariff law which was generally opposed in the Southern states. But the real issue was the authority of the national government, whether states or groups of states could block federal laws or even secede from the union, and ultimately the security of slavery.

The originator of these doctrines and driver of the crisis was one of the great political stars of the early 19th century, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. At first an ardent nationalist, Calhoun had drifted in an increasingly sectional direction and had developed a series of theories which held that states could ‘nullify’ federal laws and in fact secede from the Union. South Carolina’s decision to nullify the tariff law triggered the crisis. But that crisis reverberated throughout the country and provoked divisions in all the Southern states which anticipated on critical fronts the debates over the Civil War.

Trump imagines that Jackson, despite being a “very tough person” would have worked things out because he was “really angry that he saw what was happening with regard to the Civil War, he said, ‘There’s no reason for this.'”

Well, not exactly.

Jackson tended to personalize political conflict. But the Nullification Crisis cut to the core of one of his central beliefs: the inviolability of the federal union. Today we hear ‘nationalism’ used as a byword for xenophobia, racism and militarism. Jackson had his mix of each. But Jackson thought the crisis, what Calhoun was doing could not have been more important. He actually wanted to march an army down to South Carolina and hang Calhoun. To the extent Jackson knew about the Civil War and was “really angry” about it, he was really angry at the Southern planter aristocrats who would later start the Civil War. He was ready to go to war in 1832-33 to vindicate the union and popular democracy – two concepts that to him were basically inseparable. In other words, if we take Trump’s comments on their own terms he’s completely wrong. Jackson thought the issue couldn’t be more important and he was ready to go to war and crush the nullifiers.

We should note here that for Jackson, one of the key elements of ‘nationalism’ was his belief that popular democracy spoke most clearly when the nation spoke as a nation, not as separate polities in individual states.

The crisis was eventually resolved when South Carolina backed down and this resolution was helped along with a de facto compromise tied to tariff reduction. But the crisis spurred lengthy and fractious debates in Southern legislatures which mirrored the key questions that were to roil the country for the next quarter century. Slavery and its security in a country where the population of the non-slave holding states was growing more rapidly than the Southern ones was always a looming issue, even though support or opposition to slavery as such only came up at the margins of the debate.

What also came out of those debates was the growing salience of key aspects of Calhoun’s thought for many Southern political elites. Specifically how political minorities, in reality elite political or sectional minorities, could protect themselves and their property in an increasingly democratic polity. I don’t want to get too deep into it but Calhoun was developing a theory of what called ‘concurrent majorities’ in which different groups in society would need to sign off, as it were, on major government actions. So for instance, sure there’s democracy. But we Southerners or we planters don’t just get thrown into the national vote count. We’re a distinct group and on big decisions, we need to sign off as a group. Or we’ll leave. For Calhoun, the key groups were Southern whites and more specifically slaveholders.

Most of the key players in this period had died or passed from the political stage by 1861. But not all of them. The Jacksonians who were most vociferous in their support of Jackson’s unionism tended to be staunch unionists when the South thrust the country into Civil War in 1861, even in a number of cases where they were Southerners or from border states. The Blair family of Maryland is a noteworthy example.

I mention all this to note that the issues raised by the Nullification Crisis were not wholly alien to ones that roil American politics today: particularly, whether groups that lose out in democratic politics need to or get special rights to protect themselves against democratic majorities. I would argue this basic question is again at the center of our politics – majorities versus groups who want protections from democracy, whether this is aggressive gerrymandering, voter suppression or the voices we now here so frequently that it’s just not fair that California, for instance, has so many people.

Jackson’s historical reputation has taken quite a beating in recent years and for some very good reasons. He was a slaveholder. He presided over the expulsion of Indian tribes from the Southeast in his second term. He was a convinced racist, though this did not greatly distinguish him from the great majority of white Americans at the time, certainly for white Southerners. He has also become known for his militarism. But this is an incomplete picture. Most of the public image of Jackson today, at least in the public arena is driven by the writing of Walter Russell Meade, whose grasp of the man and the period is, I would argue, rather thin and presentist. It’s this Jackson – militarist, unilateralist, authoritarian and nationalist that Bannon is in love with and through Bannon has become Trump’s favorite President.

But history is complex. There’s another dimension to Jackson – one rooted in his devotion to the federal union above all else and his belief in popular democracy (albeit one in which only white men were included) both of which he rightly saw threatened by what Calhoun and his supporters represented.

Trump’s claim in this interview that the Civil War didn’t need to happen and could have been worked out is rooted in Southern pro-slavery revisionism (and its descendent, contemporary neo-Confederacy) and more recently in the intellectuals who were and are the seedbed of what we now call the alt-right. Both Jackson and Calhoun were slaveholders. But slavery and Southern sectionalism were Calhoun’s guidestars. The crisis of the early 1830s was his effort to draw a line, a bastardized constitutional line to protect slavery and Southern power in what he accurately believed was an inevitable conflict. On this front, in addition to his narrow misunderstanding of Jackson’s feelings ‘about the Civil War’, Trump is far more in the Calhounite tradition than the Jacksonian one. Indeed, it’s from the descendants of Calhounism that Trump draws his greatest political punch.

[Did you enjoy reading this post? Considering supporting TPM by subscribing to Prime.]