Through all the disagreements that define our politics, it is seldom questioned that Tea Party type conservatives are really, really devoted to the Constitution. They are, ‘Constitutional Conservatives’, as they put it. Indeed, many mainstream Republicans and Democrats will only criticize these folks by saying that their inflexible devotion to the Constitution is simply outdated or unworkable in the context of the changes that have happened in the United States over the last 225 years. The core premise is seldom questioned.

But this – sadly or happily, depending on your point of view, but certainly hilariously – is completely wrong. In fact, though many, many things have changed to make the politics of today almost impossible to relate to the politics of the very late 18th century, one of the main aims of the authors of the Constitution was to bring to heel the kind of folks who now call themselves ‘constitutional conservatives’. Let’s call this the Rand Paul Delusion.

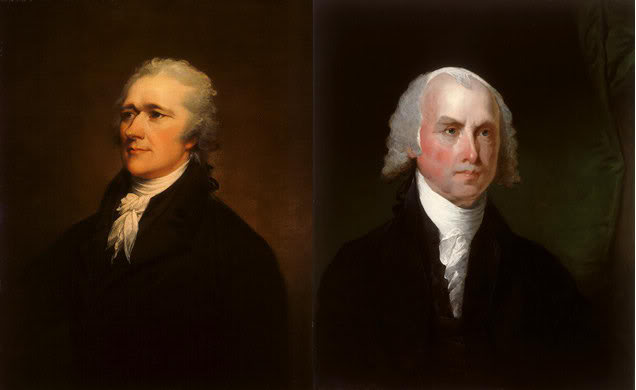

I want to write at length about this at some point. But for now let me try to approach the question in broad strokes. As most of us know, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, two young intellectuals who were defined by being just a little too young to have played significant roles in the Revolutionary crisis, were the key movers behind the constitutional project – both in pushing for the iffily-constitutional effort to convene a constitutional convention and in their successful advocacy for passage.

Their central belief was that localism and a weak national government would prevent the United States from ever achieving greatness among the states of the world and condemn it to being the plaything or pawn of the great powers of the day. State governments, far from being the anchors or liberty or legitimacy, were obstacles to progress on almost every front. And a central aim of the constitutional project was, again, to bring the states to heel.

To be clear, it’s not that Hamilton and Madison were liberals by any reasonable modern definition. In fact, in the final years of his life, Hamilton made what was probably the first effort in American history to create a political party based on the defense of Christianity – in addition to the Constitution. But in trying to create a strong state – stronger in key ways than many of us today would like – they were the polar opposites of today’s Tea Partiers.

In fact, it gets even worse.

One of Hamilton’s (and at least very early on Madison’s) core ideas was to use a national debt (and a central bank) to bind the men of wealth to the embryonic state. This was the thought behind Hamilton’s ingenious logic to have the federal government assume the revolutionary debts of the states. Not only was this a necessary inducement to get the states to ratify the Constitution. It was, as Hamilton realized, a positive good in itself.

By investing the country’s elites, the men of wealth as they were then called, in the future of the federal state (both literally and metaphorically), they could ensure its survival and growth. The wealthy and powerful wouldn’t conspire against the state if they were the beneficiaries of the state’s debt obligations. Both men looked to the example of Great Britain and how it had used its national debt to create the first modern fiscal state – with an ability to borrow, tax and spend in ways that no other state of the day could.

The brilliance of the effort was that they realized that creating a strong state required strong protections to harness and contain the state’s power. That’s where Hamilton needed Madison because it was a concern the former was not nearly as sensitive to as the latter. But it was almost entirely – and rightly – the rights of individuals that he was concerned with. The ratification process also played a key role here – in pushing for an explicit list of protections. It was a push that Madison fully embraced and one to which the moderate anti-Federalists and their intellectual descendants can point to show they ended up playing a key, formative role in the process.

There are too many examples, too many particulars to examine in one quick post. As I said, I hope to return to this topic in greater depth. It is true that you can find numerous passages in The Federalist which talk about federalism, the rights of the states and so forth. But you can only read these documents in their context when you realize that they were written not as political treatises but as advocacy – in large measure trying to reassure people who feared, with some reason, that power was being taken from the states and the localities who could more easily dominate them and place it at the center.

It’s also true that the meaning, the historical legacy of the constitution is not exhausted or encompassed simply by the ideas or aims of these two men. Indeed, Madison, who was as intellectually inconstant as he was brilliant, was just a decade later working with Jefferson on a series of documents that questioned the federal supremacy that was at the heart of the constitutional project. (Decades after that he was denying he’d ever really done that.) And the process of ratifying the constitution and the subsequent history of working out its meaning and usage gave us much of the balancing between different levels and branches of government that was not so clearly defined or intended in the document itself.

At the end of the day, though, the federal constitution was created to battle and overpower the political ideals and devotion to limited, weak government that today’s Tea Partiers and ‘constitutional conservatives’ embody. The history leaves no other possible conclusion. The central belief of the men who spearheaded the constitution was that only a strong central government could make America great and strong and thus safe. There’s a lot in those ideas that today’s liberals would not find welcoming at all. And the anti-Federalist, anti-constitutionalist strain in American history, which the Paulites and Tea Partiers of today embody, has played an important role as a counter-force. But the constitution, the aims, beliefs and goals of the constitution-makers are the polar opposite of what the Rand Paul types and Tea Partiers believe.