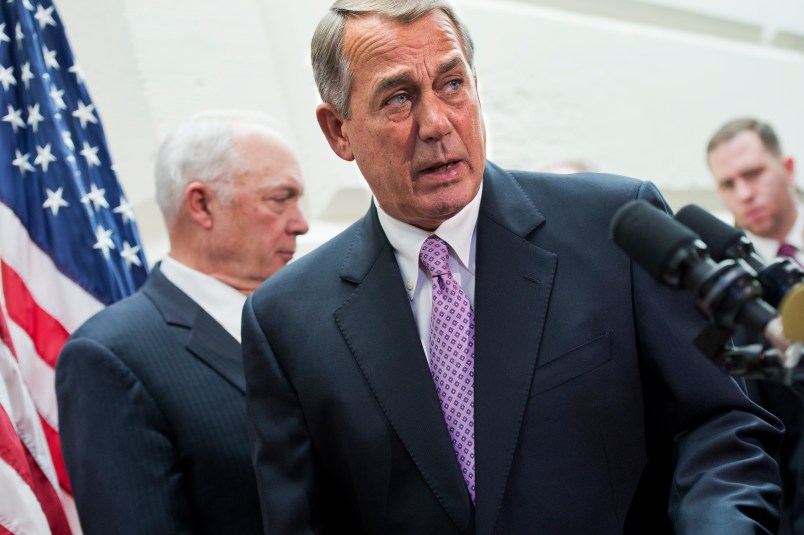

Earlier today, Speaker of the House John Boehner announced his resignation; after several years of facing a fiery, obstinate Congress, his relief was palpable. Boehner may very well go down in history as one of the most ineffective Speakers in history, but this kind of fervent opposition isn’t exactly unprecedented.

Consider two cases a century ago that make Boehner’s tenure look downright warm-and-fuzzy.

In 1910, progressive Republicans, who had deep policy differences with the regulars over business regulation, government responsibility to the disadvantaged, and political reform, challenged the power of Speaker “Uncle” Joe Cannon. Curiously, the 40 or so Republicans who joined with Democrats to strip the speaker of his membership on the Rules Committee and the power to make committee assignments did not threaten to remove him from the speakership. Cannon offered to resign but the progressives said “no, thanks.” In fact, although his power was sharply reduced, Cannon stayed in office, humiliation be damned. He was defeated for reelection to his House seat two years later, won the seat again in 1914, and stayed in the House through 1923, when he was nearly 85.

In 1923, progressives again challenged the re-election of Frederick Gillett as speaker. They forced several ballots that produced a three-way split between regular Republicans, who wanted Gillett re-elected, a progressive Republican candidate, and a Democratic candidate. To overcome the impasse, the Gillett forces gave into progressive demands for reforms, but returned to their old ways after regulars increased their numbers in the 1924 elections. Gillett gave up the speakership in 1925 to take the Senate seat he had just won in Massachusetts.

So it’s not as if Speakers haven’t been seriously challenged throughout history. But Boehner, in contrast to Cannon and Gillett, was challenged by a faction on the right that seldom articulated substantive policy differences with him, was not a threat to coalesce with Democrats to control policy outcomes in the House, and was willing to consider removing him during the middle of a Congress. Differences over party strategy made Boehner’s circumstances unique.

The history of House party leadership suggests that when a party has a sizable majority and is homogeneous in its policy outlook, as House Republicans have had during Boehner’s speakership, this is a relatively easy job. In fact, the record indicates that a homogeneous majority will empower its top leader to set legislative priorities for the party, enforce discipline when necessary, and control the legislative process in the collective interest of the party.

After his election as majority leader in 2006 to replace Tom DeLay, Boehner seemed to fit the historical pattern. A fairly unified party allowed him to set the direction for party, serve as the chief intermediary with the president, and articulate party views and direct public relations efforts.

Circumstances changed when Republicans regained a House majority in the 2010 elections and Boehner became Speaker. The new Speaker and his Tea Party colleagues differed little on policy substance, but they nevertheless repeatedly disagreed about party strategy on the most important issues. Tea Party Republicans insisted on maximizing the leverage that majority control of the House might give them. They demanded that the House majority withhold support for spending, debt limit, and other legislation until the Senate and president met their demands. They argued that their (Republican) constituents expected nothing less of them, and they pointed to the party’s continued electoral successes as evidence that playing hardball to the max works best.

Dating back to Gingrich’s gamesmanship in 1995 and continuing through the 2013 government shutdown, Boehner and perhaps most Republicans considered brinksmanship politics a failure that should not be repeated. Building their House majority, winning and maintaining a Senate majority, and, equally important, winning the White House demanded a longer-term view of the party’s policy and electoral interests. For Boehner, it certainly made little sense to hold out for legislative outcomes that could not be achieved, whatever the electoral price.

Boehner struggled with hardliners who were unwilling to accept his strategic choices. The hardliners were created by the same outside forces that generated so much of the partisan polarization in American politics. Organized groups and well-financed ideological interests recruit Republicans and back them in primaries, threaten incumbent Republicans with primary challenges if they show signs of compromise with the Democrats, and scrutinize legislators’ behavior as never before. These forces proved too strong for the man who held the most powerful position in Congress.

Steven S. Smith is the Kate M. Gregg Distinguished Professor of Social Sciences, Professor of Political Science, and the Director of the Murray Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy at Washington University. He is the author of The Senate Syndrome: the Evolution of Procedural Warfare in the Modern U.S. Senate.

I guess the takeaway is that Rethuglicans have been deeply dysfunctional for over 100 years. Is anyone surprised?

Newt didn’t get a mention? Oh right, he was just an average criminal.

Both parties have long had two wings that were in conflict with each other. Republicans had the business/industrial interests and the progressives, and Democrats had the working class/immigrants and conservative southerners. The second group of each switched parties between the 1960s and 90s, but they’re still somewhat in conflict (Republicans now more so than Democrats).

And local dynamics can be even more complicated. In Hawaii, as the plantation economy died and Democrats became ascendant, the business interests (read: developers) recognized that the best thing to advance their interests was to make common cause with the unions whose jobs are entwined with them. The result is that it’s now the most Democratic state, but a large faction of the party - heavily backed by both labor and corporations - works to minimize things like environmental regulations, even those that would help the formerly-important agricultural sector. The pro-environment side of the party, which would be most of it in most states, is smaller, while Republicans are hardly worth mentioning (some of them are actually pro-environment as well).

I think it is quite insightful to point out that Boehner is unique in being ousted as speaker for strategic, rather than policy differences. The delight the conservatives show in light of this is revealing: much of the Republican base feels a deep rage at their perceived powerlessness.