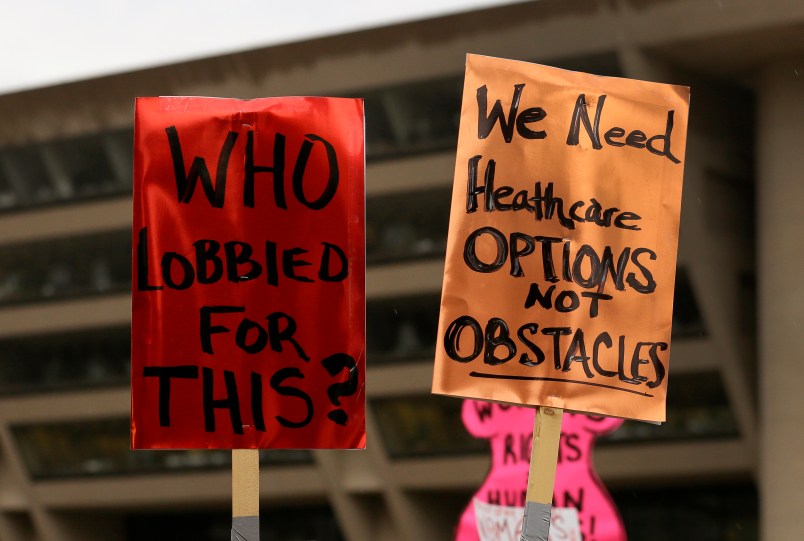

Since 2011, hundreds of anti-abortion legislative bills have been introduced and passed in the state legislatures across the country. They seek to regulate abortion in all kinds of creative ways, from bans on providing abortion via telemedicine, to mandating that clinics have local hospital admitting privileges, to requiring in-person followups for patients two weeks after their medical abortion. They focus on details like room temperature, door width, and scrub and locker room setups for abortion clinics.

These TRAP bills, or Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers, have all been drafted with the same purpose. The legislation isolates the medical act of purposefully terminating a pregnancy and requires it to have a completely different and unnecessary set of regulations and standards than any other medical procedure, regardless of whether the other procedures are more or less dangerous, common or invasive.

For abortion rights activists, as well as the judges that are consistently striking down a large percentage of these bills as unconstitutional, the repeated drafting of these bills is puzzling. After all, first trimester abortions, which account for over 90 percent of all terminations, is one of the safest medical procedure a person can undergo. While states like California are training other medical professionals to do first trimester aspiration abortions, it makes little sense that other states are attempting to not only limit which types of doctors can provide an early abortion, but even mandate who can do something as simple as hand over the pills in a medication abortion itself. Forcing a clinic to have double wide doors and no offices on an upper floor without direct outside access just to offer a termination, standards that don’t apply to other outpatient care, seems both ridiculous and punitive, and an obvious case of double standards.

But to abortion opponents, it isn’t a double standard at all. Because, to them, abortion isn’t healthcare.

That belief is what lies at the core of all anti-abortion activism, and is how they are able to repeatedly draft bills that single out abortion and abortion providers and still argue in good faith that it isn’t discriminatory to expect an abortion clinic or doctor to operate under different standards. Abortion is not healthcare, and because of that fact, regulating it should not have any implication or effect on other medical practices.

We saw that argument pop up repeatedly when the anti-abortion movement plotted to systematically remove any insurance coverage of abortion from the Affordable Care Act, and it has continued both with state based insurance bans and conscience clause laws allowing medical professionals, pharmacists and others to opt out of abortion and birth control provision. It is the backbone of the continuing battle to let religious employers opt out of birth control coverage in their insurance plans, as they willfully argue that their faith believes contraception is akin to abortion even if science disagrees.

While it has been a key catchphrase for the movement, it’s also caused some massive policy problems when abortion opponents tried to implement it in real-life legislation. In one example, the otherwise rabidly anti-abortion Mississippi legislature was forced to water down their attempt to pass a bill that would ban off-label use of the drugs used in a medication abortion during the 2013 session. The bill was amended out of fear from The Mississippi State Medical Association that doctors would have their hands bound on using the drugs for other, non-abortion related needs that would also be considered off-label. Abortion opponents responded to the new version, calling it “useless.” Despite the pushback from the medical association, activists remained unable to understand why a bill couldn’t just regulate a drug when it is used for abortion but for no other purposes.

That question is popping up again during the Iowa battle over the only large scale telemed abortion program in the country. For months the state’s medical board and the courts have been fighting over whether the board should be allowed to close the telemed abortion program, despite no patient complaints ever being filed against it in the six years that it has been in place.

The board of health—which had been filled entirely with members appointed by Republican Governor Terry Brandstad, an abortion opponent—voted over the summer that the program was “too dangerous” and that a doctor must be physically present to do an in-person exam of the patient in order to provide pills to induce an abortion. Planned Parenthood of the Heartland, who had run the satellite program, had been using medical personnel in local clinics to do intake and the physical exam and ultrasound instead, with the patient talking via video conference to the doctor at the end of the appointment and then receiving medication if the doctor approved.

Telemedicine has become a priority for providing medical care in Iowa, and one that the board of health has become heavily involved in helping to expand by creating rules and regulations for providers. This in-person requirement created specifically for abortion, but not other health procedures, flies in the face of the expansion, according to the editorial board of the Des Moines Register.

“The board showed it is willing to defy the very premise of telemedicine if the members don’t like the health service being provided,” they wrote in a recent editorial. “The board’s new rules do not require physicians providing any other health service to conduct “in person” exams or to be present when patients swallow thousands of other drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.”

But of course, anti-abortion activists don’t see that as singling out abortion, because abortion is not a health care procedure. “As do all abortion advocates, the Register’s editorial board insists that abortion is a subset of ‘health care,’ or, put another way that webcam abortions are a legitimate expression of ‘telemedicine,’” argues National Right to Life’s David Andrusko. “[N]o other drug has the intended purpose of killing someone, a small detail to the Register, but significant to anyone with an open mind. And it’s not just unborn children who die.”

The logic behind North Carolina abortion clinics’ new regulations echo Andrusko, too. In 2013, anti-abortion legislators repeatedly inserted language that would allow the state board of health to write new medical standards for abortion clinics—and only abortion clinics—into multiple bills, finally getting it passed after inserting it into a proposal on motorcycle safety. Bill supporters said the new regulations would be written just to increase patient safety and not with an intention to shutter most of the abortion clinics in the state, as other similar regulation bills had done in other states that year.

Now, nearly a year and a half later, those new rules have been released. Both abortion providers and medical experts worked with the board to ensure the rules took into account medical best practices, rather than just unattainable measures that would make clinics close. Abortion opponents, upon learning this, were disappointed.

“While the governor is trying to treat abortion like any other medical procedure, on one level that’s a good thing, but he’s really dismissing the important part,” one abortion opponent told ABC 13 News.

That “important part” the governor apparently dismissed? That abortion is not supposed to be viewed as health care.

Even the allowable “exceptions” for obtaining termination when a ban is in place shows that every line of an abortion law is written with this express idea in mind. There are no mental health exceptions because an abortion can never be needed for mental health reasons. There is no medical exception because an abortion is never medically necessary. You can have one only if you will have “irreversible harm” or permanent damage to a “bodily function” because an abortion is never required to protect a pregnant person’s health.

Abortion is never healthcare. Once you recognize this assertion as the root of every piece of legislation, every bill suddenly makes complete sense.

Robin Marty is a freelance writer, speaker and activist. Her current project, Clinic Stories, focuses on telling the history of legal abortion one clinic at a time. Robin’s articles have appeared at Cosmopolitan.com, Slate, Rolling Stone, Bitch Magazine, Ms. Magazine and other publications.

Great article. Really feel like I learned something about the issues and the tactics of the activists. Intent was never in doubt.

If abortion “is never health care,” under what auspices can they regulate it? If it is not considered health care, then it is not “medical,” and therefore how can they require hospital conditions in abortion facilities? These legalese gymnastics are easy for those who invent whatever they need to move their ideology forward, but they should not get past any court.

They claim it is to protect women, but of course it isn’t. They claim it is to protect “babies,” but their lack of support to mothers and children in need make that lie obvious to anyone with a functioning brain.

I’d be happy for Plan B, implantable contraceptives and the IUD to put abortion clinics out of business due to lack of demand. I would think everyone should agree on that, but “pro life” forces are no help whatsoever getting teenagers fitted with first-line contraceptive therapies.

I refuse to call anyone pro life whose methods include judging women, throwing up needless barriers and handing out punishments.

Pro-life is Pro-religion/Pro-politics and that is the gist of the whole deal. Even if a few individuals actually only truly have pro-life concerns, they eventually get swallowed up by the right-wing nuts and fundamentalists. Just like the teabaggers.

Pro-potential life or partial life is closer to the truth. All things alive and living aren’t fought for like the controversial, able to get votes issue, unborn babies and sperm.

Pro-life is Pure-bullshit, IOW.

Good article that explains some of the thinking and insidious strategy behind these TRAP regulations.

Also, someone recently pointed out the problems behind requiring abortion providers to have hospital admitting privileges – it seems it’s a two-pronged attack on providers:

First of all, hospital are not eager to provide admitting privileges to abortion providers because they don’t see it as a business development tool for them; since almost all abortions are done without incident, granting hospital admitting privileges would not result in an uptick of business for the hospital. So that’s one hurdle;

Second, many doctors seeking to purchase liability insurance are asked, “Have you ever been denied hospital admitting privileges?” If the doctor answers in the affirmative, he/she may be unable to buy the insurance. So being denied hospital admitting privileges could become a barrier to pursuing one’s livelihood.