I traveled to Ukraine for several days in early May.

It was something like a vacation, though that word doesn’t really come to mind when I think of the trip.

I lived in Kyiv from 2016 to the end of 2018, and had been wanting to visit for a few reasons: to spend time with people I had missed and worried about since the full-scale invasion began, prurient interest about what had changed, and a looser feeling of wanting to be close to a place undergoing so much pain.

Most of all, though, it was curiosity. And, apart from everything else, it’s a fascinating time to be in Kyiv.

To get there, I flew to Krakow, and then took a train to the Polish-Ukraine border where I caught another train to Kyiv. There haven’t been commercial flights since February 2022, so the only way in is overland.

Because it takes nearly a day of travel to reach Kyiv, you have both a lot of time to notice on what’s going on around you — refugees preparing to return home, border guards toting an assault rifle in one hand and a passport scanner in the other — but also a sense of the distances involved in international travel that commercial flight has eliminated.

Kyiv had that same quality: something oddly archaic mapped onto an otherwise-normal landscape.

Attrition from the war is immediately visible. Around half the men I saw my age were either in uniform or visibly wounded. When I asked about this, the response was even more sobering: Ukraine’s wounded-to-killed ratio is roughly three to one; the city feels empty not only because so many people have fled westwards, but because Russia’s war has caused enough death to make it visible.

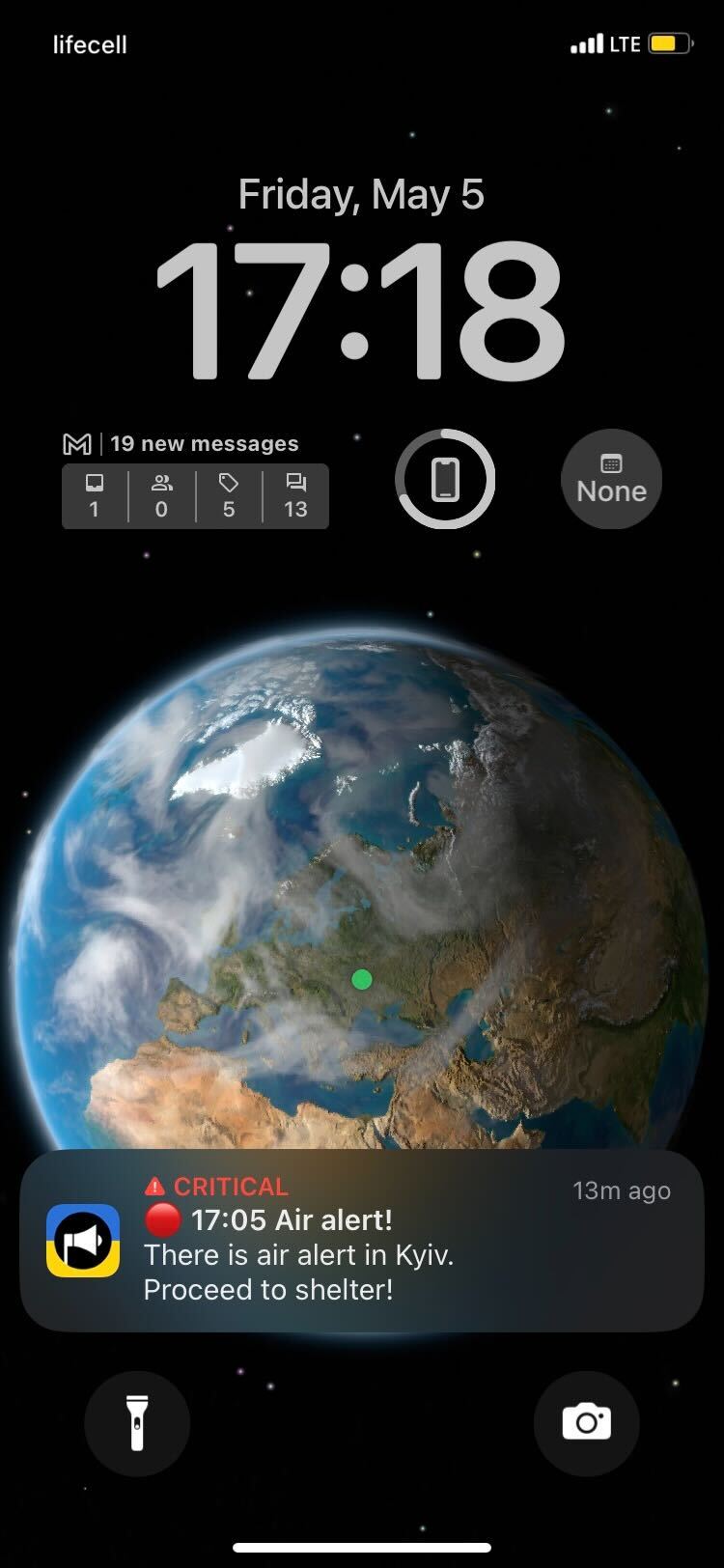

On a run one morning after an air raid, I found a spent anti-aircraft round in the middle of a track. Kyiv still maintains fortifications in case of another Russian onslaught on the capital over land: trenches are cut through some parks; concrete blocks and “hedgehog” tank traps line the medians of major streets, ready to block roads if needed again. War-themed fashion has become popular; one friend sported a t-shirt that read “War-Work Balance.” I saw one woman with a tote bag that read, “Sex is cool, but Putin’s death is better.” Everyone has an air raid app installed on their phones which sends a push notification when an air raid alert starts. Star Wars actor Mark Hamill voices it, and says “may the force be with you” to signal the alert’s end.

Kyivans are relatively safe, protected by the thickest network of anti-air defenses in the country. The Russians periodically lob missiles at the capital, and send swarms of drones.

Sirens sound if there’s a threat, but, at this point, most people don’t run for cover until they hear explosions. Russia has ballistic missiles in its arsenal and they hit faster than the speed of sound; if you hear the explosion, you’re safe, and the boom is followed by that of a rocket engine. Mobile anti-air teams drive around to shoot down drones. The experience, even when its over, reverberates throughout your body for hours and days afterwards.

Kyiv can feel a little like a modern city dragged back into darker parts of the 20th century.

Men of draft age are banned from leaving the country; the vast majority of people on my train were women, children, and the elderly. I was the only male in my train car, earning me more than a few unfriendly glances.

But on these trains, divided into compartments of four, it’s both easy and expected that you’ll chat with your compartmentmates. One woman, a widow named Lyudmyla, showed me how, in exchange for contributing money to a battalion in Ukraine’s armed forces, the soldiers were sending her personalized videos taken from what looked like the smoking ruins of destroyed buildings.

Later, on a commuter train from the Polish border to Warsaw, I chatted with another Ukrainian woman who, like me, hadn’t been to visit since the full-scale war began. That was in 2017, when she flew to Kyiv from her home in China for her grandfather’s funeral.

I had been struggling to describe the dissonance I felt, and she put it like this: a sci-fi movie where some other dimension collided with ours, creating brief moments of time travel against an otherwise normal, modern landscape. Fast food restaurants, sports, bars, people — all that was mostly intact, but with bizarre alterations, unsettling tears in the fabric of reality: tank traps outside McDonalds, people renovating the bunkers built under Stalin-era apartment buildings, homes hastily abandoned in the war’s first days taken over by vermin.

But even that sense of unreality began to feel like an especially decadent luxury afforded to me by the fact that I chose to be there, and that I had been absent from Ukraine since the full-scale invasion.

To those who live there, and particularly those who chose to stay during Russia’s partial encirclement of Kyiv at the invasion’s outset, the war has had a completely totalizing effect.

Several people who had been closer to battles, or who had stayed in Kyiv, described an intimate bond they felt with the Ukrainian army: the sense that the armed forces, personally, had saved your life.

The trauma that the war has inflicted comes out in various ways; friends chain-smoking constantly, one who had spent time in the trenches saying that he couldn’t help but feel bitter when he saw people in Kyiv smiling while knowing what’s happening elsewhere in the country. People who I formerly knew to mostly speak Russian now only use Ukrainian; one friend, Kostya, who still spoke Russian would only discuss the war in Ukrainian or English.

Another friend, Lena, moved to Chicago, and then Columbus, Ohio, as a refugee. She described to me what sounded like a liberal’s nightmare vision of the modern immigrant experience: she couldn’t afford a car, and ended up spending two hours on unreliable bus lines in Ohio in the morning and in the evening, struggling between making it to English classes, minimum wage work, and taking her two-year old child to daycare that she could barely afford. Lena eventually decided it would be easier to take her chances in Kyiv, where the government provides free childcare, and moved back.

I informally polled everyone I met there on a few questions: what had their experience been like? Did they think it was worth giving up territory for peace? What did they think about U.S. support?

The Ukrainians I spoke to seemed far more grounded and realistic in how the war was likely to go than Americans. They seemed to think it would be years before peace, saying that Russian brutality in formerly occupied areas like Bucha proved that no compromise was possible. So many people had died, they said, that the country’s 1991 borders should be preserved.

That would bring the country back not only to its state before February 2022, but to before the 2014 annexation of Crimea; the point at which most Ukrainians regard the war as truly having begun.

Though setting that all aside, many said that the main condition had to be ensuring that Russia would never do this again.

Nearly everyone brought up, without my prodding, their extreme dread at the prospect of Trump getting re-elected, assuming that it would mean an end to U.S. military support, and perhaps the end of their ability to defend themselves.

It may be unsurprising, but the war has affected everyone I spoke with in an all-encompassing way. Thanks to the air raids, and to the draft notices, people live under this absolute rule of chance, not having grown accustomed to, but now at least familiar with, the resulting anxiety and omnipresence of injury and death.

Soon after arriving, I chatted with one close friend. She was telling me about her life, and I asked her to tell me what had been going on with her — apart from work and the war.

“The war is everything,” she replied.

Members-Only Article

Members-Only Article