We’re only at just the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, and already primary care providers are warning that their medical practices might not survive the pandemic.

The issue is not just treating the coronavirus itself, though primary care providers are facing the same challenges plaguing hospitals, with a lack of testing, equipment shortfalls and a need to keep their staff virus-free.

But the overall shift away from in-person interactions has overnight turned the landscape for health care on its head, scrambling the financial model for medical practices that Americans rely on for routine and minor medical issues.

Those providers are now warning that, without a major influx in cash or a change to how business is done, they might need to close their practices in weeks, not even months.

“What’s going to happen right now is our staff is going to get paid and we’re going to pay our bills, because that’s what we do,” said Christi Siedlecki, the CEO of Grants Pass Clinic in Oregon. “But our physicians aren’t going to get any money — they’re the owners — and when our physicians don’t get any money, they’re going to leave, and when they leave, my practice will die.”’

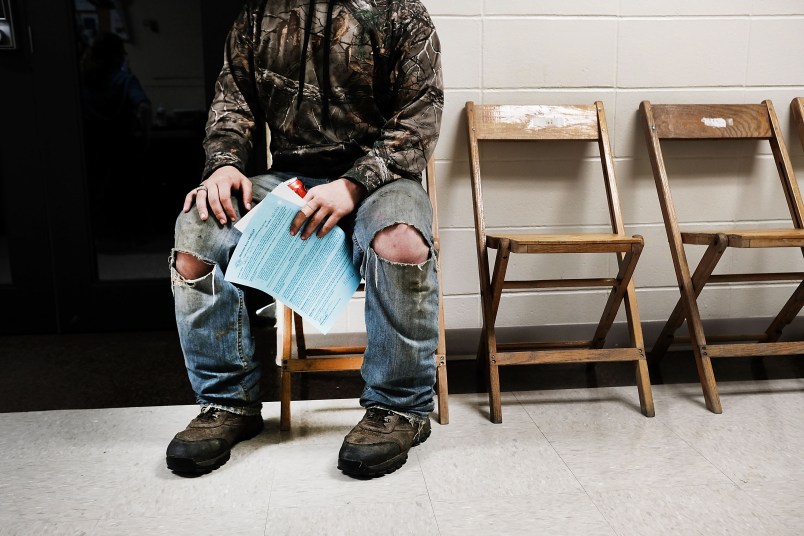

In normal times, most primary care physicians largely get paid based on in-person visits. Public health experts are now discouraging people from leaving their homes — including in cases where they’d normally see a doctor for a health issue, but can instead seek medical advice over the phone or using other remote technologies.

While this directive is preventing the spread of the virus to doctors and other patients, it’s also taking a bulldozer to their practices’ bottom lines.

“Our doctors are telling their patients, don’t come into the office, which means that the offices are not making any money,” said Farzad Mostashari, the CEO of the firm Aledade, which helps health practices adopt new technology. He said his firm helped doctors send 130,000 postcards to patients telling them to stay home.

Many of these practices operate on thin margins, Mostashari said, and already the doctors that own them are forgoing their salaries.

“They’re really, really worried about how many weeks they can last before they literally have to shut their doors at a time when we need that frontline capacity,” he said.

In lieu of in-person visits, patients have been encouraged to use telehealth, i.e. getting care from their doctors through internet portals and other forms of electronic communication. But doctors usually get paid less for virtual consultations — in some instances, far less — and even when telehealth visits are incorporated into the business, appointments are way down.

The Trump administration has loosened the regulations around telehealth to facilitate the shift, and made payments through Medicaid, Medicare and other federal health programs more generous on that front, if still a little short of what doctors would get for an in-person visit.

“The government has been a good partner and is paying well for virtual and telehealth visits, but not all the private payers are following [the government’s’] lead,” Shawn Martin, the CEO-designee of the American Academy of Family Physicians, told TPM.

There is also a push to secure a boost in payments for audio-only phone calls, which patients who aren’t technologically savvy depend on.

“The phones are ringing off the hook. We can’t keep up phone volume,” Jennifer Aloff, a doctor at the Michigan practice Midland Family Physicians, told TPM. Nonetheless, actual appointments — including telehealth visits — that bring in the bulk of her clinic’s revenue are down significantly, from more than a 100 per day to about five a day.

“The workflow is not the same,” Martin said. “They’re not going to see as many people in an hour virtually as they would in person.”

The financial strain the pandemic is putting on clinics is being felt everywhere, not just in areas that are getting pummeled by the virus at the moment.

Beyond the desire to make sure these clinics are still standing at the end of the pandemic, there is the more immediate concern of making sure they’re fully functional for if and when the virus spreads to those still relatively-isolated communities.

In just the span of days since the virus hit the U.S. in earnest, community health centers — which are the only option for primary care for some Americans — were forced to impose staff furloughs and layoffs, according to Steve Carey, the chief strategy officer of National Association of Community Health Centers.

“We need to be made whole, for when this coronavirus is actually upon us,” Carey said, describing the message his organization was receiving from its members.

If primary care doctors do shutter their practices while the virus is still raging, the fear is that their most routine patients —older people and those with chronic issues — will have to turn to hospital emergency rooms and urgent care facilities to get treatment, putting them at greater risk to contract the virus.

“Imagine if, for every condition any person has, the only place you could get care is the emergency room during the COVID emergency, that wouldn’t be very good,” Mostashari said.

Primary care Docs have been putting their patients in major financial pinches for decades.

Johns Hopkins now indicates that there are 510,000 confirmed cases so far.

And the US is only 5,000 cases behind Italy, and rapidly catching up

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

Mango Voldamort & the scamming crew will be getting a big payout through hotel bailouts coupled with loopholes in defining ownership & ‘small businesses’. Meanwhile, using it as another excuse to undercut anyone who actually does productive work.

OK, I admit it: Trump was right – I am tired of all the winning!

Trump’s delays and prissy posturing may turn out to be the deadliest factor to this virus.

We had a game plan. It looks like Trump and his team totally demolished and ignored it. Anticipating the effect on healthcare resources is in the damn document.