CHICAGO (AP) — Our food was a little less safe, our workplaces a little more dangerous. The risk of getting sick was a bit higher, our kids’ homework tougher to complete.

The federal government shutdown may have seemed like a frustrating squabble in far-off Washington, but it crept into our lives in small, subtle ways — from missed vegetable inspections to inaccessible federal websites.

The “feds” always are there in the background, setting the standards by which we live, providing funds to research cures for our kids’ illnesses, watching over our food supply and work environment.

So how did the shutdown alter our daily routines? Here’s a look at a day in the life of the 2013 government shutdown.

WAKING UP

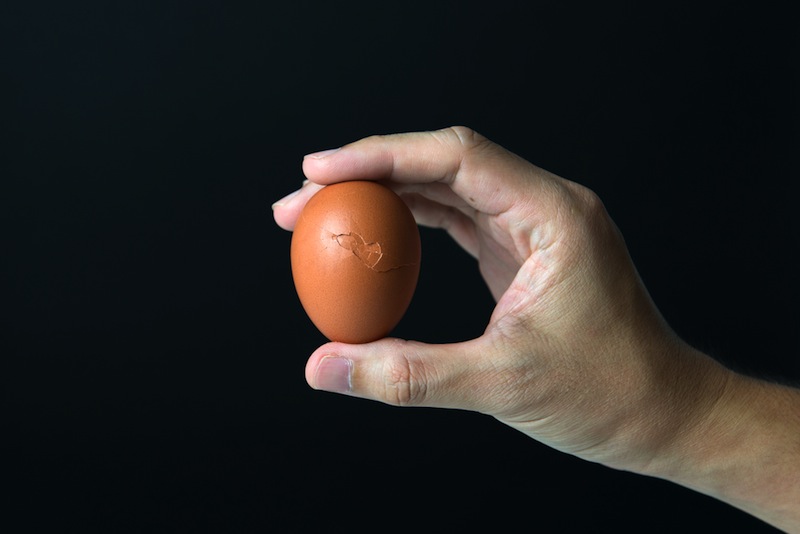

That sausage patty on your breakfast plate was safe as ever because meat inspectors — like FBI agents — are considered “essential” and remained at work. But federal workers who inspect just about everything else on your plate — from fresh berries to scrambled eggs — were furloughed.

The Food and Drug Administration, which in fiscal year 2012 conducted more than 21,000 inspections or contracted state agencies to conduct them, put off scores of other inspections at processing plants, dairies and other large food facilities. In all, 976 of the FDA’s 1,602 inspectors were sent home.

About 200 planned inspections a week were put off, in addition to more than 8,700 inspections the federal government contracts state officials to perform, according to FDA spokesman Steven Immergut. That included unexpected inspections that keep food processors on their toes.

It worried Yadira Avila, a 34-year-old mother of two buying fruit and vegetables at a Chicago market.

“It’s crazy because they (the FDA) sometimes find the bacteria,” she said.

The FDA also stopped doing follow-ups on problems it previously detected at, for example, a seafood importer near Los Angeles and a dairy farm in Colorado.

And what about the food that made it to your plate? The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, which furloughed 9,000 of its 13,000 workers, said the shutdown slowed its response to an outbreak of salmonella in chicken that sickened people in 18 states.

OFFICE HOURS

At a warehouse, factory or other worksite, a young minority exposed to racial slurs by his boss had one fewer place to turn for help. Federal officials who oversee compliance with discrimination laws and labor practices weren’t working, except in emergencies.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission was not issuing right-to-sue letters, so people could not take discrimination cases into federal court, said Peter Siegelman, an expert in workplace discrimination at the University of Connecticut’s law school.

Workplaces weren’t inspected by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. One result? Employees could operate dangerous equipment even if not trained or old enough to do so.

“The afternoon before the shutdown we got a complaint of a restaurant where a … 14-year-old was operating a vertical dough mixer,” said James Yochim, assistant director of the U.S. Department of Labor’s wage and hour division office in Springfield, Ill. “We (were) not able to get out there and conduct an investigation.”

Yochim’s office also put on hold an investigation at another restaurant of children reportedly using a meat slicer.

HOME SAFE

Getting around was largely unaffected. Air traffic controllers were on the job, flights still taking off. Trains operated by local agencies delivered millions of commuters to their jobs.

But if something went wrong, such as the mysterious case of a Chicago “ghost train,” people were left in the dark.

On the last day of September, an empty Chicago Transit Authority train somehow rumbled down the tracks and crashed into another train, injuring a few dozen passengers. The National Transportation Safety Board dispatched investigators, and they kept working when the shutdown started the next day because they were “essential.” But the agency furloughed others whose job is to explain to the public what happened.

So millions of commuters used the transit lines without knowing more about what caused the crash.

The CDC slashed staffing at quarantine stations at 20 airports and entry points, raising chances travelers could enter the country carrying diseases like measles undetected.

In the first week of the shutdown, the number of illnesses detected dropped by 50 percent, CDC spokeswoman Barbara Reynolds said. “Are people suddenly a lot healthier?” she wondered.

STUDY TIME

Children learned the meaning of shutdown when they got home and booted up computers to do homework. From the U.S. Census bureau site to NASA maps, they were greeted by alerts that said government sites were down “due to the shutdown.”

Linda Koplin, a math teacher in Oak Park, a Chicago suburb, asked her sixth-grade pupils to use a reliable online source to find the highest and lowest elevations.

“They were able to find all the elevations for the rest of the continents but they couldn’t find information for their continent,” Koplin said.

It was the same at New Trier High School in Winnetka, Ill., where social studies teacher Robin Forrest said government statistics are more important because of so much dubious information on the web.

“We try to steer our kids toward websites and databases that are legitimate, the same way we would college students,” he said.

NIGHT, NIGHT

After hours is when the shutdown arrived at many people’s homes.

Monique Howard’s 5-year-old son, Carter, has the most trouble with his asthma at night, when his breathing is labored. Her family dreams of a cure, the kind doctors are hunting through federally funded research grants at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

During the shutdown, the doctors had to stop submitting grant applications to study childhood asthma and other diseases and disorders. Hospital officials said the shutdown could have delayed funding for nearly half a year.

“I have met some of these doctors who are close to breakthroughs, and if this sets us back five or six months, it just seems to me like a lot of these studies are going to be scrapped or they will have to restart them,” Howard said. “It’s just so frustrating as a parent.”

There was a comedic effect, too. The shutdown might have saved raunchy entertainers from punishment for obscene or offensive language on late-night TV and radio.

The Federal Communications Commission investigates broadcast misbehavior only if viewers or listeners complain. During the shutdown, callers heard a voice with a familiar ring: “The FCC is closed.”

Copyright 2013 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Kenishirotie / Shutterstock.com