Senate Republicans have used the filibuster to block a bipartisan bill that would establish a January 6 commission to investigate the Capitol insurrection.

Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME), Mitt Romney (R-UT), Ben Sasse (R-NE), Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), Rob Portman (R-OH) and Bill Cassidy (R-LA) voted alongside Democrats to break the filibuster and advance the bill to a floor debate. That effort fell short of the 10 Republicans needed.

The final tally was 54 yes votes to 35 no votes — some senators had already left for the holiday weekend.

The vote was expected to happen Thursday afternoon, though it was derailed amid chaos over an unrelated bill about American technological competitiveness. An agonizingly long amendment vote process, drawn out further by Sen. Ron Johnson (R-WI) and other Republican senators who speechified about wanting more time to read the amendments, dragged into early Friday morning and kicked the commission vote down the road. The Senate finally started votes on the commission bill Friday afternoon.

All told, 11 senators skipped town before the vote: two Democrats, Sens. Patty Murray (D-WA) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ), and nine Republicans, Sens. Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), Roy Blunt (R-MO), Mike Braun (R-IN), Richard Burr (R-NC), Jim Inhofe (R-OK), James Risch (R-ID), Mike Rounds (R-SD), Richard Shelby (R-AL) and Pat Toomey (R-PA).

Toomey’s office said in a statement that he would have voted in favor of advancing the commission bill if he’d been present.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) hinted in a dear colleague letter after the vote that he may bring it to the floor again.

“Senators should rest assured that the events of January 6th will be investigated and that as Majority Leader, I reserve the right to force the Senate to vote on the bill again at the appropriate time,” he wrote.

McConnell and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) have tried to rebrand the commission as the brainchild of Democratic congressional leaders, though the bill they’ve worked to kill was crafted by the bipartisan team of House Homeland Security committee chair Bennie Thompson (D-MS) and ranking member John Katko (R-NY).

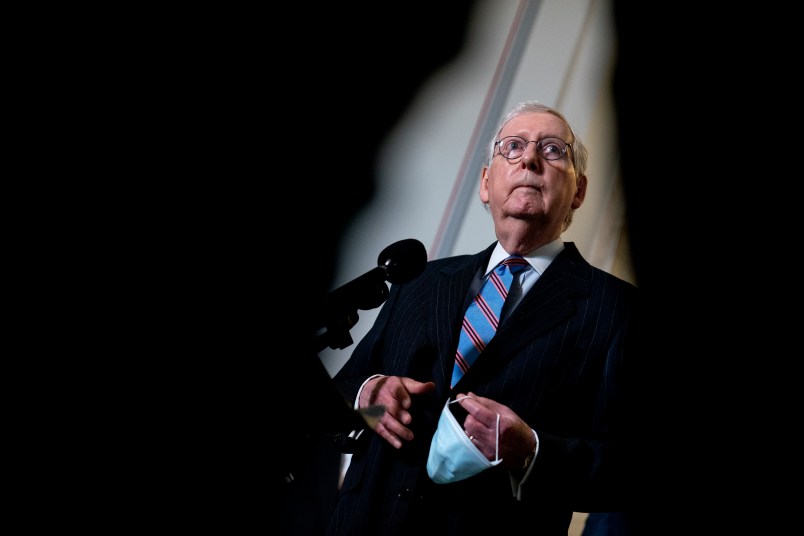

“I do not believe the additional extraneous commission that Democratic leaders want would uncover crucial new facts or promote healing,” Senate Minority Mitch McConnell (R-KY) said on the Senate floor Thursday. “Frankly, I do not believe it is even designed to do it.”

The bill got 35 Republican votes in the House, despite McCarthy and McConnell publicly coming out against it before then. The climb in the Senate always seemed steeper, though, due to the extremely high number of Republicans needed to circumvent the filibuster.

While Democrats have had to negotiate around the threat of filibuster since the start of the Biden presidency, this is the first time they’ve invoked cloture and forced Republicans to use the maneuver to block legislation.

The dynamic prompted speculation that Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), an outspoken supporter of both the filibuster and the January 6 commission, might soften his position on the former. But that speculation was scuttled earlier Thursday, when he told reporters testily that he’s “not ready to destroy our government” and encouraged faith that 10 Republicans would support the bill. They, unsurprisingly, did not.

“I don’t think they’re thinking about it from the standpoint of President Trump as much as thinking about whether we need another investigation and whether this is a political exercise, or a legitimate one,” Romney told reporters of his GOP peers. “My own view is that we should have this commission, but obviously I’m in the minority of my party.”

In the days immediately following the insurrection, Romney’s position was not such a lonely one.

Sens. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) and Johnson came out in support of an independent commission staffed by nonpartisan security experts on January 13. Both men voted against the bill on Friday.

There was even some potential movement in favor of the commission as recently as last week — Sen. Mike Rounds (R-SD) told reporters he supported an independent commission — but that largely died off as soon as McConnell came out against it. He has lobbied his members extra hard this week, asking them to vote against the commission as a “personal favor,” according to CNN. Former President Donald Trump, for obvious reasons, demanded that Republicans oppose it as well.

Many Republicans have been candid about their opposition: they don’t want the commission to spill over its December 31 end date and pollute the midterms, reminding voters that the leader of their party and some of its members stoked the flames. Any functional commission would investigate Trump’s culpability, the results of which could only hurt the party that continues to stand behind him.

There is some personal risk for members as well: McCarthy, for example, would almost certainly be asked to testify about a phone call he had with Trump as the insurrection unfolded, during which his reported attempt to cajole the former president to call off the mob ended in shouted expletives.

There are other avenues for a commission to be created, and they could be composed in a way to avoid the pitfalls of the bipartisan setup, where Republican leadership could appoint GOP firebrands loath to put any blame on Trump or his allies. The bipartisan bill also required cooperation from at least one Republican appointee to issue subpoenas, a tool Republican commissioners could have used to hamper the investigation.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) could now set up a select committee, which would only need to pass through the Democratic-majority House and would be peopled by current members. President Joe Biden could also set up a committee through executive order, funded by executive branch discretionary spending.

Those solutions, too, seem imperfect. Any commission created by Democrats alone — and its findings — would be disregarded by Republicans. Still, a bipartisan commission obviously had its own problems, beginning and ending with the ultimate question: how can a party investigate a crime it had a hand in provoking?

This post has been updated.

Your move, Senator Manchin.

Manchin, you wanted attention, you’ll get all the attention you ever wanted.

Joe M is looking under the sofas (ala Shrub looking WMD’s) for ten “good” Qpublicans.

Somebody give that bastard a kick in the ass while he’s bent over looking.

Yeah, think now he’ll realize that our government is broken?

Betting he doesn’t.

Fuck you, MoscowMitch.