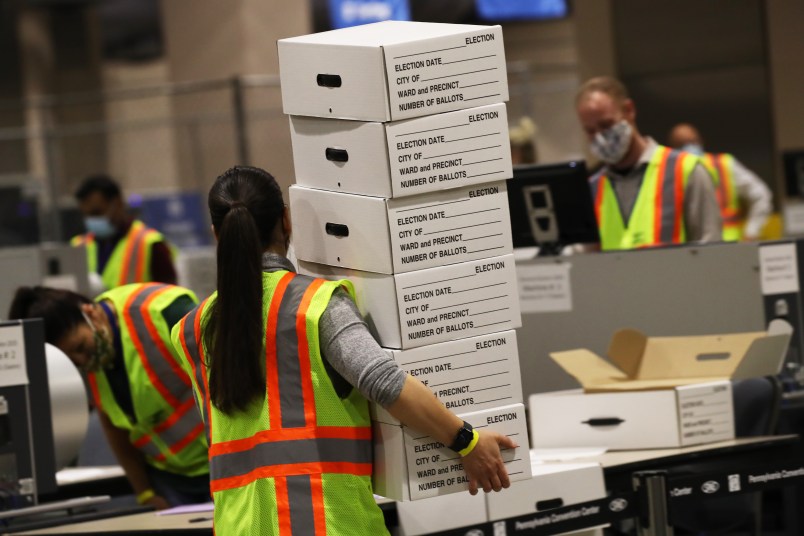

Election officials are facing threatening behavior, crushing work hours and low pay, according to a new report that examined the work atmosphere around election administration amid President Trump’s 2020 fear-mongering.

The Bipartisan Policy Center teamed up with The Brennan Center, a non-partisan voting rights think tank connected to New York University Law School, to publish the findings of a survey of 233 election officials.

It found that one in three election officials felt unsafe in their jobs, and that about one in six had faced threats related to their work. Nearly 80 percent of the election officials called for their governments to provide security protection to election officials when needed.

“Election officials we spoke to saw a direct link between election disinformation and the violence and threats they experienced in conjunction with the 2020 election,” the report said. “Indeed, 54 percent said they believe that social media, where disinformation about elections took root and spread, has made their jobs more dangerous.”

Even more — 78 percent of the officials in the survey — said that social media has made their jobs more difficult, in part because of how it helps spread misinformation and disinformation.

Election officials described taking drastic steps to deal with the surge in calls, emails and other outreach they received during 2020 election, fueled by the disinformation and misinformation being spread by the internet.

Orange County, California’s Registrar of Voters Neal Kelley set up a call center to field the barrage of inquiries based on incorrect information, which amounted to “thousands” of calls, according to the report.

This onslaught was a drastic increase from previous election cycles, the report said, citing the account of Cathy Darling Allen, county clerk and registrar of voters in Shasta County, California.

“Individual calls could take upwards of 15 to 20 minutes, as those who called were generally unwilling to accept truthful information,” the report said.

“Finally, nearly every election official we spoke with expressed concern that disinformation about elections would exacerbate the difficulty of retaining and hiring good staff,” the report said. Those concerns come as the workforce skews white — 94.1 percent of those in Brennan’s survey identified as white — and older. Those 50 or older made up nearly three-quarters of the survey takers; a quarter of the respondents were 65 or older.

The report also described the attempted political interference election officials faced.

“Several” election officials shared stories with the Brennan Center about “partisan actors — including elected officials, party leaders, and partisan activists — attempted to interfere with the conduct of the election or to pressure them to favor candidates of their own party, both publicly and privately.”

Election officials were facing this pressure while stuck in grueling work conditions, the report said.

“One local election official shared that she and her team worked ’70–80 hours a week for two and a half months,'” the report said. “Another local election official reported working 110-hour weeks for six weeks straight during the 2020 election cycle.”

Vacation time, meanwhile, goes unused amid the demands of the job.

“One local election official in a moderately sized jurisdiction had 12 weeks — or two and a half years’ worth — of unused vacation time,” the report said. “A state election official reported that he has more than 500 hours of unused leave, much of which he is on the verge of losing for lack of use.”

The pay skews low — election officials on average receive $50,000 — and is well lower than the $70,000 median for other commiserate local officials.

“Just over 45 percent of local election officials from jurisdictions of 5,000 or fewer registered voters reported that they are paid less than $35,000, with over a quarter earning less than $20,000,” the report said.

The report laid out solutions that it recommended policymakers consider for addressing these challenges. Among them were proposals for better funding mechanisms for election administration; overhauls to the government structures around elections, to better insulate them from political interference; and actions social media platforms can take to combat disinformation.

Only one in three? Republicans have work to do.

“Several” election officials shared stories with the Brennan Center about “partisan actors — including elected officials, party leaders, and partisan activists — attempted to interfere with the conduct of the election or to pressure them to favor candidates of their own party, both publicly and privately.”

And of these “several”, how many have been reported so they can be investigated?

Beat me to it.

I think this was the point.

We have an unfortunate tradition of treating our essential workers like pond scum, that the pandemic has brought home to these folk like never before. And employers wonder where their employees are. They should get a clue.

In this case, I hope the DoJ will pull out all the stops in protecting election workers. They are essential to a healthy, vibrant democracy.

We have our work cut out for us. We all suffer with no Democracy, including the Republicans.

Huh? Do they think that the Predators behind the rank and file have the latter in their hearts?