The 2010 midterm elections were, in Barack Obama’s words, a “shellacking” for Democrats—and not just those in Congress.

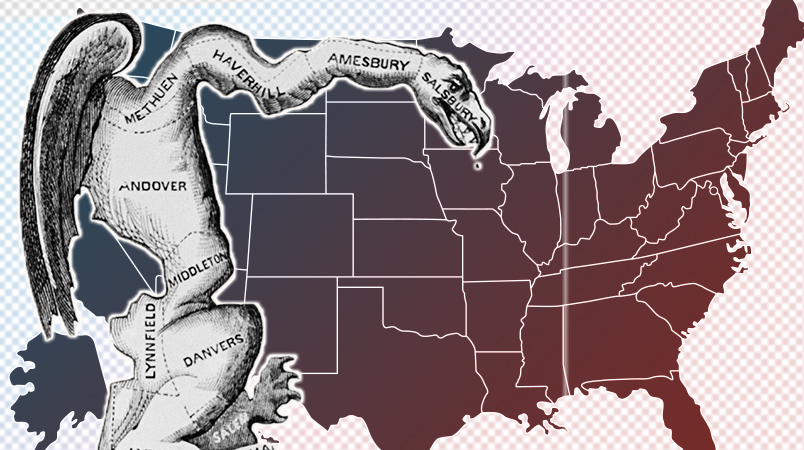

That was the year Republicans poured money and resources into key state legislatures in order to control the once-a-decade redistricting process that would follow. The GOP emerged with full control of numerous key states, allowing them to draw congressional and state legislative district lines to their advantage, and giving them a major edge in elections for the rest of the decade. In 2012, Democrats won 1.4 million more votes for the House than the GOP, but wound up with 33 fewer seats.

With the next Census less than two years away, Democrats are mobilizing to try to prevent the same thing from happening again. But going further, by setting themselves up to carry out their own gerrymander, doesn’t appear to be on the agenda—at least for now.

The National Democratic Redistricting Committee (NDRC), backed by Obama and spearheaded by former Attorney General Eric Holder, is teaming up with other Democratic campaign organizations to target specific governorships, legislative chambers, and ballot initiatives in 2020 with an eye on getting a say in the redistricting process.

So far, at least, Democrats appear focused more on fighting for fairer maps than on letting themselves draw maps that advantage their party.

“Our goal is to restore fairness to the system,” NDRC Communications Director Patrick Rodenbush told TPM Thursday. “If you look at our list of target states, we’re trying to break trifectas in states that were most badly gerrymandered by Republicans and then protect against gerrymandering in a handful of other ones.”

Trifectas are where one party controls all three influence-points for the redistricting process: both legislative chambers and the governorship.

Indeed, in many of the states the NDRC is targeting like Florida, Georgia, and Texas, their goal is only to have a voice in the redistricting process by winning control of one chamber or the governorship—not to win total control in a way that would’ve them a free hand to gerrymander. That’s in part because winning full control isn’t realistic in many states.

“The NDRC is saying all the right things and it might be that they would be happy with fair districts,” Justin Levitt, a redistricting expert at Loyola Law School, told TPM. “In some places that’s all they’re going to get, by the way. I will see what happens when they actually get control of states. I’ll see if they put their money where their mouth is.”

Still, even where they end up with the power to do so, there are plenty of factors that may keep Democrats from pressing their advantage. Demographics are a central one.

“Democratic voters are badly distributed geographically,” Theodore Arrington, a voting rights expert at University of North Carolina at Charlotte, told TPM in an email. “They are very concentrated in urban areas. Therefore, it is difficult to avoid creating a number of districts that are heavily Democratic, which wastes their votes. Given that the courts will look for districts that are compact and follow other traditional districting principles, this bad concentration will hurt the Democrats.”

The U.S. Supreme Court is currently weighing three major redistricting cases out of GOP-gerrymandered Wisconsin and Texas, and Democrat-gerrymandered Maryland. Those cases could set limits on how extreme partisan gerrymanders can be.

Whatever they determine, the energized Democratic base is also pressing leadership to move towards a fairer system where independent arbiters draw up maps based on neutral redistricting principles that better reflect the parties’ vote shares. These grassroots activists appear motivated as much by a commitment to small ‘d’ democratic principles as by a partisan desire to maximize Democratic gains.

“Post-2016, people have elevated the issue of redistricting from something that was obscure—that we had to engage in a civics lesson on—to something that’s pretty much their number one demand,” said Kathay Feng, national redistricting director at Common Cause. “Wherever we go to, this has been a rallying cry.”

That energy has already prompted significant movement in two states that were heavily gerrymandered in Republicans’ favor during the last cycle. Ohio’s legislature approved a bipartisan resolution that would put an independent commission in charge of the congressional redistricting process, which voters will now decide on in May. Voters in 2015 approved an initiative to create a similar commission to handle state legislative redistricting. And in Michigan, a reform group collected over 425,000 signatures late last year for a 2018 ballot initiative that would install a similar setup.

“I think the biggest reformist impulses from the inside right now are coming from places where citizens are angry and loud about it,” Levitt, the Loyola professor, said. “And the legislators are desperately trying to get ahead of what they fear to be a loud angry tidal wave against them.”

That’s not to say all blue states or Democratic lawmakers are on board, or have been in the past. In Maryland and particularly Illinois, Democrats drew districts that protected incumbents. In Illinois, House Speaker Michael Madigan campaigned against a 2016 effort to create an independent redistricting process that garnered over 500,000 signatures. In California, state Democratic leadership fought hard against an ultimately successful reform initiative to create a similar process despite strong support from local Democratic clubs, according to Common Cause’s Feng.

But the party at large seems to recognize that simply having fairer maps rather than ones that heavily favor Republicans will benefit them in the long run.

Democrats are in the “comfortable position of being able to advocate for fair maps knowing that, number one you occupy the high ground,” said Tom Bonier, a Democratic political strategist and CEO of marketing consulting firm TargetSmart. “It’s hard to argue against transparency and public input. But they also know that fair maps would produce a much better landscape for Democrats.”

Non-partisan redistricting advocates like Feng hope that once that system is in place and voters see the benefits, they’ll be less likely to have to engage in another all-out battle with the GOP again in another ten year’s time.

“I analogize this to The Lord of the Rings,” she said. “You gotta take this ring away from them and throw it in the volcano. The power to draw lines for the next ten years to benefit yourself, your party and your buddies is very tempting to hold onto. And it brings out ugly monsters in both parties.”

Throwing the ring away, Feng said, is “the only way we can move beyond this tug-of-war.”

I believe the technical term is “vulnerable to predation.”

Funny thing is that even in most states they controlled in 2010 Democrats did a bad job of redistricting. In Arkansas Democrats controlled the process and drew a map that FAVORED the GOP, instead of drawing 2 safe dem and 2 safe GOP districts they went for the old 3-1 split that demographics no longer supported and lost all 4 seats. In Illinois because of parochial concerns Democrats didn’t do what they should have when they could easily have drawn 1 more seat. Let’s not even talk about New York where the corrupt Independent Democrats cost Democrats control of the state Senate and where Democrats could have easily drawn 4-5 more Democratic seats (Hi Perter King welcome to representing parts of Queens!)

That’s the problem with Democrats, we are to nice and fair. We need to kick the Republicsns where it hurts. That’s what they do to us.

Redistricting should be done on a national level, using a single computer program, that takes into account only population and natural boundaries. The source code for this program should be publicly available for inspection, I am sure there are enough people with the proper expertise on both sides of the aisle to ensure that there was no partisan data included.

Unlike repugnicans with their gerrymandering and voter suppression efforts, Democrats actually believe in democracy.