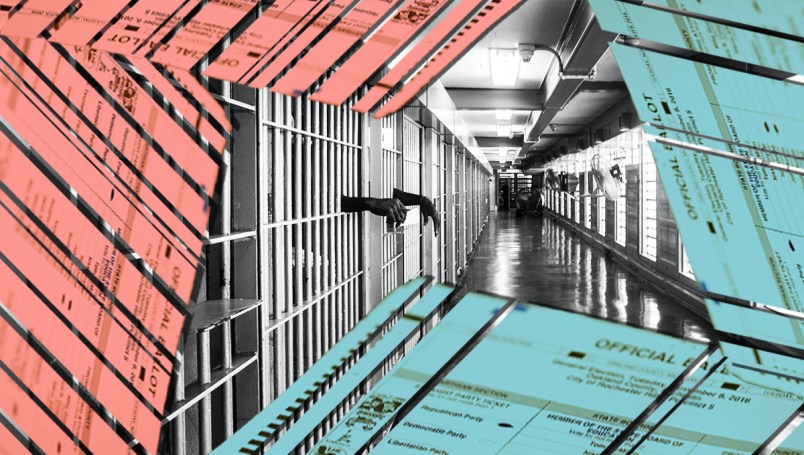

In Louisiana, criminal offenders released from prison often linger in the purgatory of parole for years, or even decades, stripped of key civil rights. Because the Bayou State only restores voting rights to felons who complete probation or parole, some who get caught up in the system die before regaining the franchise.

Those are the people whom state Rep. Patricia Smith wanted to help last year. Smith introduced a bill to restore voting rights to felons who’ve been on parole without problems for five years after their release from prison, as well as those who are on probation for five years. After three rounds of revisions, the bill passed the House in a squeaker of a vote, sailed through the Senate, and was signed into law as Act 636 by Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) last May.

But in December, stories started appearing in the local press suggesting that the law may apply to many more people than the 2,000-3,000 it was expected to affect. The actual number, according to advocacy groups and state prison officials, may be more like 36,000.

Secretary of State Kyle Ardoin (R) has conceded that Act 636 would restore the franchise to thousands more felons than anticipated. His office is now tasked with sorting out the law’s implementation with only weeks to go before it goes into effect on March 1.

Smith and Voice of the Experienced (VOTE), an ex-offender advocacy group that backed the measure, insist they were never trying to mislead anyone or create confusion. They maintain that officials surprised by the varying numbers were simply not paying attention to what the law said.

“I think it’s just that they don’t even understand who they disenfranchise,” Bruce Reilly, an ex-offender-turned-lawyer who now serves as VOTE’s deputy director, told TPM in a phone interview.

“It’s just a matter of people speaking on or having authority over a subject area they don’t really have any real knowledge in,” Reilly continued. “Any public defender or prosecutor could tell you this stuff.”

VOTE is threatening to sue Ardoin’s office if he does not end up implementing the broader interpretation of the law.

The Secretary of State’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment after requesting questions via email. The Department of Corrections did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

So far, at least, there appears to be little backlash from the Republican and independent lawmakers who voted for Act 636 despite opposition from their more conservative colleagues. TPM reached out to every GOP House member who voted for the bill and is still in office, but did not receive responses back.

Some lawmakers, though, have expressed confusion over why the 36,000 figure didn’t receive much play until months after Act 636 become law. And Louisiana conservatives like political science professor and blogger Jeff Sadow have suggested that the GOP was “fooled into adding thousands of Democratic voters.”

The numbers hinge on the byzantine, baffling categories of probation and parole in Louisiana, known until last year as “the prison capitol of the world.”

Act 636 was specifically aimed at restoring the franchise to the narrow pool of people on probation and parole who have been out of prison for five years with no significant infractions.

The language of the law refers specifically to an individual “under an order of imprisonment for conviction of a felony and who has not been incarcerated pursuant to that order within the last five years.”

But some 34,000 Louisiana residents on probation are never sent to prison at all, or are sentenced to probation for less than five years. Rep. Smith and VOTE say that Act 636 should keep those individual from losing their voting rights, too.

“When you have people who fall under various laws for probationers, it’ll be hard to say that some people on probation can vote and some can’t,” Smith told TPM. “If one group of felons can vote, why can’t this other group, based on what this law brings into play?”

This broader group of probationers received little attention during contentious debates over the bill. VOTE’s Reilly told TPM he brought them up at the first House and Governmental Affairs Committee hearing on the legislation, telling lawmakers that anyone not incarcerated as part of their probation sentence “would be allowed to vote” if it passed.

As the Times-Picayune recently reported, the Secretary of State’s office also agreed in a legal brief last summer that Act 636 would restore voting rights to probationers who’ve never been imprisoned. VOTE had sued the state over its prohibition on probationers and parolees voting; Ardoin’s office countered that the suit should be tossed because the affected population had their grievances addressed by Act 636.

But Smith, conservative lawmakers who pushed for the bill, and prison officials are all on the record estimating that around 2,000-3,000 people would be affected by the legislation before it was voted on last spring. Smith told TPM that she never meant to misrepresent on this point.

“I did not think it was only going to cover 2,000-3,000 people,” she said. “We knew it was going to affect some probationers as well.”

Smith said the Department of Corrections did not provide a timely estimate of the total number of probationers who would be affected, so she couldn’t pass this information on to colleagues who asked about it.

The Democratic lawmaker said she thinks her law “probably would have” passed even if the higher estimates were widely discussed.

Smith and other state lawmakers agree that interpretation is now in the hands of the Secretary of State, who did not support the expansion of ex-felon voting rights and has said he doesn’t think the broader reading of the law reflects the will of lawmakers. Ardoin is supposed to be sorting out these details with the Department of Corrections, but the Times-Picayune reported negotiations have yet to get underway.

Litigation is possible, depending on what understanding they reach.

But VOTE’s Reilly, who would help bring that lawsuit, said he hopes it can be avoided. Restoring voting rights to this broader swath of people wouldn’t swing elections in the state or put public safety at risk. Instead, he said, it would restore the franchise to tens of thousands of people who didn’t commit a crime serious enough to land them in prison.

“For those of us who have been held accountable for certain things, paid our so-called dues, paid the price, suddenly a little bit of voting rights is okay but a lot of voting rights is a problem,” Reilly said. “Is Louisiana happy when turnout is 15 percent? Does that make for a better democracy?”

“Between gerrymandering and racial divisions, if this was anyone’s way of strategically winning elections, it wouldn’t be a great strategy,” Reilly continued. “But if you want people to feel like a part of their community, that they’re actually doing something positive, why wouldn’t you restore their voting rights? If you want us to behave pro-social, why don’t you act pro-socially towards us?”

Another notable positive to getting rid of unconstitutional double jeopardy laws and allowing the right to vote for every citizen. Even if it was a mistake.

So it sounds as if some people didn’t even realize that someone sentenced to probation only would have lost the right to vote. But yeah, no way a court is going to rule that someone sentenced to 10 years in prison and 10 years probation after that gets their vote back while someone sentenced to three years probation doesn’t.

GOP mantra: if you can’t win the popular vote cheat likely Dem voters out of their voting rights. Despicable!

So who is head of the Dept. of Corrections?

And in LA how many defendants get probation instead of a prison sentence? What’s the break down by race? And what’s the longest term of probation a defendant has been sentenced?

Interesting that it’s the number affected that’s the issue, not the appropriateness restoring voting rights under certain circumstances. The South has a sordid history of turning misdemeanor infractions into felony charges specifically as a means of disenfranchising the black population wholesale. Guess the GOP simply forgot how successful their repression efforts have been.