Now that President Obama has signed health-care reform into law, opponents of the bill are pinning their hopes of stopping it on a last-ditch legal strategy. A group of 13 state attorneys general has filed suit (pdf), arguing that the law is unconstitutional.

The bid seems far-fetched at first. But the Roberts Court has recently shown a willingness to strike down landmark legislation — charges of judicial activism be damned. So, given the stakes, it’s worth asking: Could health-care reform have made it through the congressional gauntlet, only to end up dying in the courts?

(Late Update: The Justice Department is signaling that it’s already gearing up for a fight. “We will vigorously defend the constitutionality of the health care reform statute,” a DOJ spokesman says.)

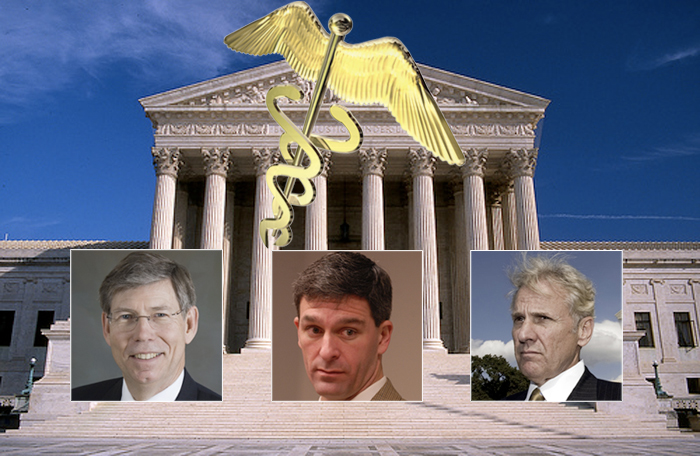

In recent media appearances, the AGs — the most high-profile of whom have been Ken Cuccinelli of Virginia, Bill McCollum of Florida, and Henry McMaster of South Carolina — have made a grab-bag of claims, among them that the bill violates state sovereignty. That’s a contention that no court is likely to have much time for. As Steve Schwinn, an associate law professor at John Marshall Law School has written, state laws that aim to override the federal mandate “are almost surely unconstitutional, as conflicting directly with the federal requirement.”

The stronger argument in the arsenal of the AGs — many of whom happen to be running for governor — relates to the Commerce Clause, the section of the Constitution that empowers Congress to regulate interstate commerce. The AGs focus on the provision of the bill that requires almost all Americans to obtain health insurance. They argue that imposing a penalty on people merely for declining to buy insurance is outside the scope of Congress’s power under the Commerce Clause. “For the federal government to be telling people that they must buy health insurance, or they must buy anything at all, is not one of the powers that is give to the federal government by the Constitution,” McMaster declared on Fox yesterday. “Nowhere does it say that the federal government can require a private citizen to go out and buy health insurance or anything else. It’s not a part of the Commerce Clause power.”

This argument isn’t, as some reform supporters may wish to see it, merely a bizarre and desperate concoction of the far-right wing — akin, for instance, to the pseudo-legal arguments advanced by “Constitutionalists” for why Obama’s presidency is illegitimate. Over the last six months, it’s been embraced by several respected conservative legal scholars. And more importantly, an emerging jurisprudence from the conservative court does show a willingness to limit the scope of the Commerce Clause.

Last September, David Rivkin and Lee Casey, former Justice Department lawyers during the Reagan and Bush 41 administrations who played prominent roles in support of the Bush 43 administration’s detention policies, noted in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that in a 1995 case, U.S. v. Lopez, the Supreme Court invalidated a law that made it a crime simply to possess a gun near a school, holding that the law did not “regulate any economic activity and did not contain any requirement that the possession of a gun have any connection to past interstate activity or a predictable impact on future commercial activity.” Likewise, Rivkin and Casey wrote, a health-care mandate also wouldn’t regulate any “activity.” “Simply being an American would trigger it.” (Late Update: Rivkin and Casey are listed on the lawsuit (pdf) as “of counsel” to the plaintiffs.)

Randy Barnett, a professor of constitutional law at Georgetown Law School, agrees. “The individual mandate extends the commerce clause’s power beyond economic activity, to economic inactivity. That is unprecedented,” he wrote in a Washington Post op-ed that appeared this weekend. “Regulating the auto industry or paying “cash for clunkers” is one thing; making everyone buy a Chevy is quite another.”

A July 2009 paper (pdf) for the conservative Federalist Society by Peter Urbanowicz and Dennis G. Smith, two former HHS officials, took a similar view. “While most health care insurers and health care providers may engage in interstate commerce and may be regulated accordingly under the Commerce Clause, it is a different matter to find a basis for imposing Commerce Clause related regulation on an individual who chooses not to undertake a commercial transaction,” they wrote.

But this view is by no means widespread, even on the right. Numerous constitutional scholars say the mandate is well within the scope of what the court has defined as commercial activity — pointing to the 2005 case, Gonzales v. Raich, in which the Supreme Court found that the federal government could criminalize the growth and possession of medical marijuana, even when it was limited to within a single state, on the grounds that doing so was part of an effort to control the interstate drug trade.

Erwin Chemerinsky, the dean of the UC Irvine School of Law, noted in an op-ed in Politico last October that health-care coverage is far more closely related to commercial activity, and the national economy, than is the private growth of marijuana. “In 2007, health care expenditures amounted to $2.2 trillion, or $7,421 per person, and accounted for 16.2 percent of the gross domestic product,” he wrote. And, he argued, the Supreme Court has never said that only people who are themselves engaged in commercial activity can be regulated under the commerce clause. For instance, the court found that the Commerce Clause could be used to require southern restaurants and hotels to serve blacks, even though what was at issue was their refusal to engage in commercial activity.

Jack Balkin, a constitutional law professor at Yale Law School, extends that argument. In a recent blog post, he notes that in the Raich case, Justice Scalia found that Congress can use the Commerce Clause to regulate, as Balkin put it, “even non-economic activities if it believes that this is necessary to make its regulation of interstate commerce effective” (itals TPM’s). People who don’t buy health insurance, Balkin argues, aren’t simply “doing nothing,” as Rivkin, Barnett et al. claim. These people pass on their health-care costs by going to the emergency room, or buying over-the-counter cures. “All these activities are economic, and they have a cumulative effect on interstate commerce,” writes Balkin.

Several respected conservative legal experts essentially agree that the court would have to radically break with past rulings to strike down the law. John McGinnis, a former Bush 41 administration Justice Department official and a past winner of an award from the Federalist Society, told TPMmuckraker that the court could rule in favor of the AGs only by taking a radical Originalist view of jurisprudence — one that all but ignores precedent. “I think the only person who shares [that view] is Justice Thomas.” said McGinnis, now a constitutional law scholar at Northwestern Law School. “It’s a very difficult argument to make under current precedent.”

Doug Kmiec, a former Reagan administration Justice Department official, and conservative legal scholar, echoes that view. “The idea that a regulatory requirement (whether to purchase insurance or to purchase a smoke alarm) violates the Constitution by exceeding the scope of the commerce power was rejected in the age when Robert Fulton’s steam ships were at the center of case controversy and the proposition has not gained validity with the passage into the 21st century,” Kmiec, now the Obama administration’s ambassador to Malta, told TPMmuckraker.

And Orin Kerr, a professor at George Washington Law School, who has served as a special counsel to Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) and clerked for Justice Anthony Kennedy, likewise believes the bill is almost certain to pass muster. “I think it’s very very unlikely that the mandate would be struck down as unconstitutional,” Kerr told TPMmuckraker.

There’s another problem with the lawsuit. Many judges are often reluctant to hear a challenge to a law until it has actually gone into effect — what legal types call a “ripeness” issue. The individual mandate won’t go into effect until 2014 — by which time factors like the composition of the Supreme Court, and the underlying politics driving the lawsuit, may well have changed.

So what do these disagreements among experts mean for how the court is likely to rule? In short, how confident can we be that reform will survive the challenge?

Frederick Schauer, a constitutional law scholar at the University of Virginia, expresses what seems to be the most reliable view. He notes to TPMmuckraker that in the Lopez case, and in a subsequent 2000 case involving the Violence Against Women Act, the Supreme Court has held that there are limits on what constitutes commercial activity under the Commerce Clause — shifting from the “anything goes” approach that had predominated since the New Deal. Despite the subsequent medical marijuana ruling, Schauer says, those cases offer the “slightest glimmer” to opponents of the bill — but not much more than that. So twenty years ago, said Schauer, there would have been essentially no chance of the court striking down the legislation. Today, he says, “it’s a real long-shot,” but not completely out of the question.

There’s something else worth considering, though. The fears of reform supporters rest in part on the worry that the Supreme Court’s five conservative justices will simply ignore the relevant jurisprudence and use their authority to make a nakedly partisan ruling — as, many argue, they already did not so long ago.

That seems highly unlikely. Striking down health-care reform, despite the clear weight of evidence that it fits well within the scope of the Commerce Clause, would “be more aggressive than Bush v. Gore,” says Kermit Roosevelt, a constitutional law professor at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. “They’re probably not eager to do that again.”