Yesterday — ten days after the failed Christmas bombing attempt — there were anthrax scares in both Alabama and California.

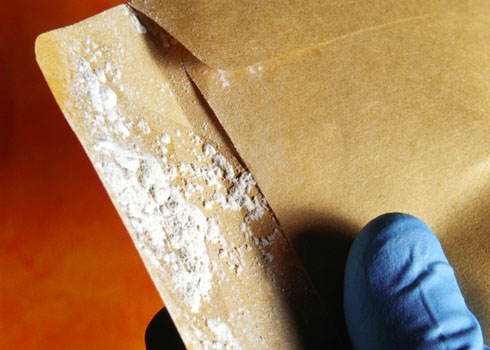

Envelopes containing white powder were sent to the district offices of senators and congressmen, as well as to a federal courthouse, in five different Alabama cities, and were believed to come from the same source. None of the letters tested positive for anthrax or any other harmful substance.

The letters were sent to the offices of senators Jeff Sessions and Richard Shelby, and congressmen Jo Bonner and Mike Rogers, all Republicans, in the cities of Mobile, Foley, Anniston, and Montgomery. Letters containing the powder were also sent to the federal courthouses in Anniston and Birmingham.

Meanwhile, two professors at the University of California, Irvine, yesterday received letters containing white powder and a message reading “Black Death.” The Orange County Health Department quickly determined that the powder in both letters was harmless.

The professors were Cynthia Feliciano, from the sociology department, and Nancy Da Silva, who teaches chemical engineering and materials science.

A movie by the name “Black Death,” about a major outbreak of bubonic plague in 14th century England, is scheduled to come out February 26th. It’s unclear whether the mailings were related.

What’s going on here? We all remember the anthrax attacks of fall 2001, when envelopes containing the toxic substance were mailed to the offices of congressional leaders like Tom Daschle, and top news media personalities including Tom Brokaw. Coming in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the mailings seemed designed to play on America’s heightened fear of terrorism at the time, and set off a widespread panic.

Could yesterday’s mailings be similarly designed to take advantage of the (milder) climate of fear created by the failed Christmas bombing attempt?

The idea doesn’t seem far-fetched — though so far, investigators don’t appear to have come up with any evidence that points in that direction.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that these anthrax scares don’t always follow major terror attempts. For instance, in October, 2008, a Sacramento man was arrested after several news outlets, businesses and a congressman received threatening packages in the mail containing a substance, found to be harmless, marked “Anthrax sample.” And in January 2009, employees of the Wall Street Journal’s Manhattan office were evacuated after a dozen envelopes containing white powder — also later found to be harmless — turned up.

So it may be that these scares simply attract more attention, and are more likely to turn into national stories, when they come in the wake of a major terror attempt, when people are already on edge.

But it’ll be worth keeping an eye on the investigations in Alabama and California as they go forward.