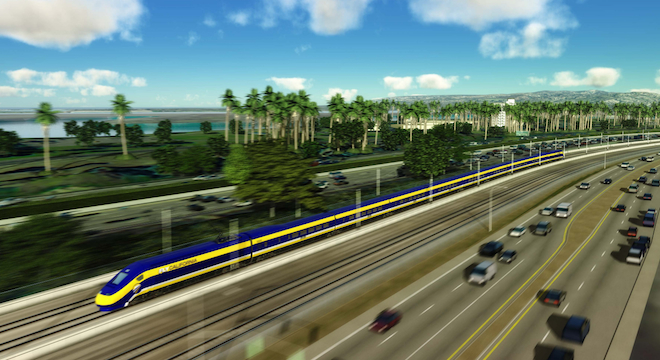

In California, the car is still king. But that could be a different story by 2028 — when a proposed massive, 520-mile-long high speed rail project, intended to span the state from north to south, Sacramento to San Diego, is supposed to be completed, ideally making the Golden State into America’s first-ever bullet train hub.

But the project, which is projected to be able to take riders from Los Angeles to San Francisco in 2 hours and 40 minutes, traveling at up to a peak of 220 miles-per-hour in some sections, costs an estimated $68 billion and is backed vociferously by Democratic Governor Jerry Brown, has run into heavy interference recently.

The California Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO), an independent state budget watchdog agency, on Tuesday released a cautionary report on the project proposal, recommending that legislators vote down the Governor’s plan to fund the initial phase of the project — which would connect Madera, just north of Fresno, to north of Bakersfield — by selling $2.6 billion worth of state bonds.

If the sale doesn’t go through, the high-speed rail project will effectively be stuck in limbo for the foreseeable future, as the bond sale is necessary to raise enough money to begin construction and to receive $3.3 billion in federal matching funds. In total, federal funding is supposed to pay for 61 percent of the project. Only 4 percent of these funds have been secured so far, according to the LAO, and it’s that uncertainty that has the agency urging caution.

Brown’s office isn’t so optimistic as to think all of the remaining federal funding will come through, so they’ve devised an alternate and somewhat controversial, funding source: auction revenues from the state’s own cap-and-trade program if the federal funding fails to materialize.

The LAO report, prepared by economist and policy analyst Brian Weatherford, concludes that “funding for the project remains highly speculative and important details have not been sorted out,” namely whether Washington will be able to provide federal matching funds later down the road, say in 2020, when the project is half-finished.

Yet the report still advocates that “some minimal funding be provided to continue some of the planning efforts that are currently underway,” although not specifying exactly how much.

“Our concerns are really legitimate and serious,” Weatherford told San Jose Mercury News, “We don’t really see how you could get [the money from Washington] to build this thing. That’s our primary concern.”

Following the report, on Wednesday, the California state Senate and legislature launched their first hearings on the finalized version of the project. While no final decisions were made, a prevailing attitude emerged: slow down, with lawmakers on both sides stating that they wouldn’t be able to come to a conclusion within eight to ten weeks, coming uncomfortably close to the August 31 majority vote deadline necessary to get the project started on time.

Still, the U.S. High Speed Rail Association (USHSR), a lobbying group founded in 2009 to push high-speed rail projects across the country, believes that both the LAO report and legislature’s skepticism are only temporary roadblocks, ones that will eventually be overcome by public and industry pressure in favor of high-speed rail.

“The tide is turning in favor of high-speed rail,” said Andy Kunz, founder and president of USHSR, in a telephone interview with TPM. “Sure there will always be entrenched interests against it…this is a huge paradigm shift for the country, anytime you begin a paradigm shift, there will be battles and fights with existing power brokers, because they’ll do everything they can to prevent change. But high-speed rail is inevitable.”

Kunz pointed to steadily rising gas prices and the woes of California’s interstate system, such as gridlock and congestion, as pressure points that would shift public opinion in favor of high-speed rail, and thus, voter sentiment.

But gridlock and congestion primarily occur in dense metropolitan areas, and the high-speed rail project would skirt those, or rather, switch over to traditional, slower-speed commuter rails, at least under the latest proposal unveiled on April 2nd by the California High Speed Rail Authority, the state agency in charge of the projects.

“For congestion within metropolitan regions, the highspeed rail offers no solutions, except that it compliments or substitutes commuter rails in Los Angeles or San Francisco” said Samer Madanat, the director of transportation studies at the University of California, Berkeley, in a telephone interview with TPM.

Madanat and his colleagues at Berkely’s Civil and Environmental Engineering school have vocalized their doubts about the project before. They were asked by the state Senate to do an analysis of ridership projects by the California High Speed Rail Authority back in 2010. Those findings concluded that initial ridership estimates were flawed, and that it was “not possible to predict whether the proposed high-speed rail system will experience healthy profits or severe revenue shortfalls.”

Madanat, for his part, candidly told TPM that if he “were in charge of deciding where to put a high speed rail project, from a technical standpoint, California is not the geographic location in the U.S. where highspeed rail is most needed.”

In Madanat’s perspective, the problems California faces with congestion and gridlock can only be solved by expanding commuter rail systems within metropolitan regions, not between them, as the high speed rail system would seek to do.

“High speed rail is certainly justified in the Northeast corridor,” Madanat told TPM, citing the more fully developed commuter and light rail systems already available in the region, which would be able to augment a high speed rail system.

“A system extending from Boston to Washington, D.C., through New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore would make sense,” he said. “All the appropriate factors are there: population density, existing public transit density. I would start in the Northeast corridor.”

However, Madanat told TPM that the issue was now so politicized, it was out of the hands of technical experts. Madanat said that if the project did manage to get approved and turned out to be a boon for the state and for commuters, it still wouldn’t necessarily prove that high speed rail projects should be undertaken in other parts of the country.

“Each region would need to compare themselves to the conditions that led to success,” Madanat said, “If they don’t have these conditions, then they have an incentive not to go forward.”

But Kunz and his colleagues at USHSR disagree, arguing that high speed rail makes sense in several of the most populous regions of the country. In fact, as Kunz told TPM, private investors have already expressed an interest in backing high speed rail projects, once the initial investment and legal wrangling are dealt with by governments.

“There’s a whole line of private sector folks ready to invest in the project,” Kunz told TPM.

As evidence, he pointed to a videotaped talk given to the USHSR’s New York office in November 2011 by one Robert Dove, a managing director “focusing on infrastructure opportunities” for the wealthy private equity firm the Carlyle Group.

“We manage a massive $150 billion dollars of capital for institutions, pension funds, high net worth individuals, endowments, insurance companies and other money management groups, and they are looking for good, long term investments with superior returns,” Dove said in his presentation, adding, “Looking at where all the rail tracks are and all the people are, you can identify, in our mind, four areas: the West coast, Texas, Chicago and the Northeast corridor…”

“Every one of those areas, if they had a high speed rail system, could make billions of dollars in profits,” Kunz annotated.

Still, Carlyle’s Dove clearly states in the video that the Northeast corridor is “the one where we think is the most obvious and the most likely to receive private capital in the short term.”

Carlyle declined to elaborate on Dove’s comments for this story.

The newest proposal for California’s speed rail system scales the project back from a November 2011 estimate of the project, which would’ve cost an estimated nearly $100 billion, a far cry from the about $45 billion envisioned when it was first approved by voters a lifetime ago (at least in political and economic terms), back in 2008.