The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday struck down California’s law restricting the sale of violent video games to minors, saying that the law was overly broad and ineffective.

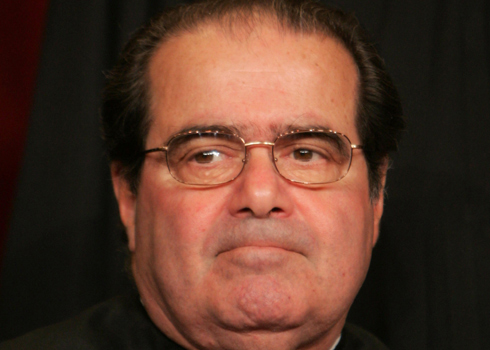

“This country has no tradition of specially restricting children’s access to depictions of violence,” wrote Justice Antonin Scalia in a 7-2 opinion.

Joining Scalia in his conclusion about California’s law Monday were Justices Anthony Kennedy, Ruth Bader Ginsberg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan.

Justice Samuel Alito filed a concurring opinion, which Chief Justice John Roberts joined. Justices Clarence Thomas and Stephen Breyer dissented.

While the court handed the video game industry a victory, the justices disagreed about the nature of video games, as well as about the extent of the backup role the state should play for parents in controlling what influences their children’s lives.

Scalia wrote that California’s law would have created an entirely new category of speech unprotected by the First Amendment, and that was speech directed at children.

He also said that the law wouldn’t have achieved the goal of protecting children from depictions of violence and its purported psychological effects because it only targeted one medium.

Scalia wrote:

Since California has declined to restrict those other media, e.g. Saturday morning cartoons, its video-game regulation is wildly under inclusive, raising serious doubts about whether the State is pursuing the interest it invokes or is instead disfavoring a particular speaker or viewpoint.

California also cannot show that the Act’s restrictions meet the alleged substantial need of parents who wish to restrict their children’s access to violent videos.

Scalia noted that the court had recently rejected the idea of creating special categories of speech that could be exempted from First Amendment protection under certain conditions.

He referred to last term’s decision that struck down a federal law that made it a crime to make videos depicting certain kinds of animal cruelty.

Books like Dante’s Inferno, Grimm’s Fairy Tales and The Odyssey are full of horrific violence, Scalia noted, and everyone’s free to read those works.

“California claims that video games present special problems because they are ‘interactive,’ in that the player participates in the violent action on screen and determines its outcome,” Scalia wrote. “The latter feature is nothing new: Since at least the publication of The Adventures of You: Sugarcane Island in 1969, young readers of choose-your-own adventure stories have been able to make decisions that determine the plot by following instructions about which page to turn to.”

The justices in the majority also didn’t buy the shaky studies that lawmakers had used to justify the law. They said that the studies merely showed correlation and not causation.

In concluding, Scalia noted that California’s law “is the latest episode in a long series of failed attempts to censor violent entertainment for minors.”

The court isn’t against the sentiment, he wrote, but it has to do its job of making sure that the such efforts aren’t overly broad, or ineffectively narrow to achieve an aim that impinges upon the First Amendment.

Justice Alito agreed that the California law isn’t as precise as it needs to be to survive a First Amendment challenge. But he vigorously disagreed with Scalia’s comparison of violent video games with other forms of media, and he described at length several kinds of emerging technologies that are making video games ultra-realistic.

“In considering the application of unchanging constitutional principles to new and rapidly evolving technology, this court should proceed with caution,” he said. “We should make every effert to understand the new technology. We should take into account the possibility that developing technology may have important societal implications that will become apparent only with time.”

For example:

… think of a person who reads the passage in Crime and Punishment in which Raskolnikov kills the old pawn broker with an axe … Compare that reader with a video-game player who creates an avatar that bears his own image; who sees a realistic image of the victim and the scene of the killing in high definition and in three dimensions; who is forced to decide whether or not to kill the victim, and decides to do so; who then pretends to grasp an axe, to raise it above the head of a victim, and then to bring it down; who hears the thud of the axe hitting her head and her cry of pain; who sees her split skull and feels th sensation of blood on his face and hands.

For most people, the two experiences will not be the same.

Chief Justice Roberts agreed with Alito’s analysis.

Justice Thomas, for his part, dissented and said he would have not held that the law is “facially unconstitutional,” and he would have reversed and remanded the case for further proceedings.

He wrote:

“In my view, the “practices and beliefs held by the Founders” reveal another category of excluded speech: speech to minor children bypassing their parents … The historical evidence shows that the founding generation believed parents had absolute authority over their minor children and expected parents to use that authority to direct the proper development of their children.”

Meanwhile, Justice Breyer also dissented. He said that he would have upheld the law as constitutional on its face. He thought the majority’s idea that California’s law would create a “new category of speech,” was overstated.

He said that the law doesn’t stop anyone from playing the games (if a parent is willing to help a child.) It merely “prevents a child or adolescent from buying, without a parent’s assistance, a gruesomely violent video game of a kind that the industry itself tells us itself tells us it wants to keep out of the hands of those under the age of 17.”

Predictably, the video game and entertainment industry hailed the decision, but State Senator Leland Yee, who’s running to be San Francisco’s Mayor, accused the court of siding with corporate interests. He also said he was encouraged by the dissenting opinions, and suggested he would try to re-introduce another version of the legislation.