Edible car contests are a fixture at college campuses and grade school science classes, where whacky fun combines with an exercise in engineering and imagination, but it seems that foodstuffs are no longer confined to scale models.

But as illustrated by Ford’s newly announced use of soybean oil to make engine gaskets and seals, car makers are beginning to turn in all seriousness to vegetation in their search for lighter, more durable, and potentially less expensive materials.

Plant matter is sprouting up as an ingredient in new car parts along with conventional materials such as rubber and plastic.

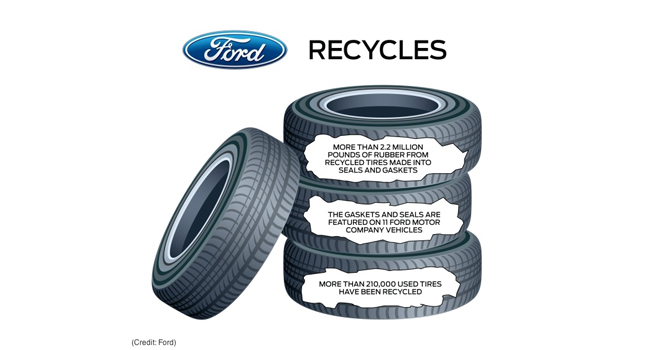

Someday in the future, perhaps some car parts might ultimately become compostable. Bur for now, it’s a sustainability goal that’s probably pretty far off in the future. Ford’s new gaskets, for example, are still made partly with post-consumer recycled tires, as well as soy.

However, the new bio-based car parts do represent a positive drive in the direction of sustainability for the world’s billions of vehicles, by relying more on renewable materials as well as recycling.

When subbing in for heavier, conventional materials, lighter bio-based car parts can also contribute to improved fuel efficiency.

Ford is staking out a leadership position in the field. In some of its models, soy already serves to make foam for seat cushions, which can be covered with bio-plastic fabric. Conventional plastic filled with straw is replacing heavier all-plastic parts.

And a company called Ecovative has come up with a way to custom-grow fungus into packaging that replaces Styrofoam. It could be used as a filler for dashboards and bumpers.

Another common plant in your driving future may be the dandelion, which is being investigated by Ohio State University’s Agricultural Research and Development Center as a source of natural rubber.

If that sounds a bit far-fetched, one need only look to history: During the Second World War, when natural rubber from the Brazilian rubber tree was in short supply, chemical engineers worked on a substitute made from milkweed.

The common denominator is the milky, saplike substance that oozes out when you break the stem.

Meanwhile, a team of researchers in Brazil is developing a plastic for use in vehicles that is made from — of all things — bananas.

The team used a high tech pressure cooker to reduce banana fibers to cellulose in the form of a nanoscale powder, which can be used to reinforce conventional plastic or replace it altogether.

The result is a banana-based material that is almost as tough as Kevlar, but is 30 percent lighter than conventional plastic.

The cellulose powder can also come from pineapples or almost any fruit source. It can also come from plant-based industrial wastes such as pulp sludge from paper mills. That translates into more opportunities for diverse communities to participate in the car manufacturing economy.

The search for renewable car parts is also taking researchers beyond flora and into fauna.

A research team from the University of Delaware, for example, is developing a way to store hydrogen in carbonized chicken feathers, for use in hydrogen-fueled vehicles.

Current technology for onboard hydrogen storage is expensive, mainly because hydrogen has to be stored under very high pressure as a gas, or very low temperature as a liquid.

At room temperature and pressure, the range of a 20-gallon tank of hydrogen would only be about a mile.

In contrast, the Delaware team estimates that the range of a 75-gallon carbonized chicken feather tank would be about 300 miles just for starters.

The hydrogen-powered chicken-mobile of the future isn’t just ready yet, however. Researchers still have to figure out how to scale the technology.