TINA CASEY

NASA scientists are working on a new spacecraft that can chase after comets, dodge chunks of debris while locking into a stable position as they rotate, and fire off a retrievable harpoon that returns to the craft with soil samples, which eventually make their way back to a laboratory on Earth.

The point of all this is to collect samples without having to land on the comet’s surface, an understandably tricky endeavor. In high-risk environments like comets, a landing would most likely bring the mission to an abrupt end — as Captain Ahab discovered when instead of landing his whale he landed on it.

Another advantage of the harpoon concept consists in the line that would tether the harpoon to the spacecraft. A free orbit around a comet would be difficult to stabilize because comets have practically no gravity. The harpoon line would hold the spacecraft in a set position above the surface until the harpoon extracts itself.

The concept of a harpoon-shooting spacecraft sounds simple enough, but in addition to the other challenges NASA engineers must figure out how to get the craft to meet up with a typical comet traveling at speeds up to 150,000 miles per hour.

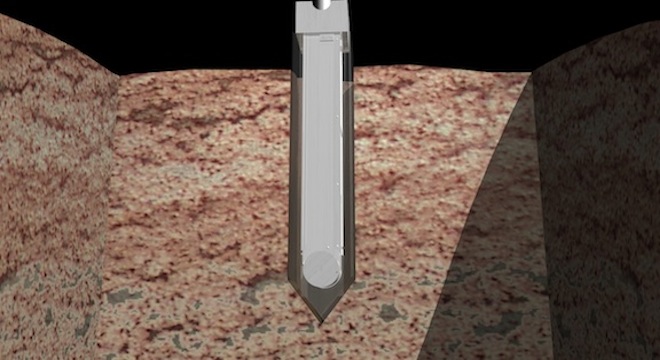

NASA scientists at the Goddard Space Flight Center have put that question aside for now and are concentrating on designing the harpoon. Though relatively small, the harpoon tip needs to pack all the equipment needed to penetrate a surface, collect samples, and extricate itself. Lead engineer Donald Wegel explained in a NASA release:

“We’re not sure what we’ll encounter on the comet – the surface could be soft and fluffy, mostly made up of dust, or it could be ice mixed with pebbles, or even solid rock. Most likely, there will be areas with different compositions, so we need to design a harpoon that’s capable of penetrating a reasonable range of materials. The immediate goal though, is to correlate how much energy is required to penetrate different depths in different materials. What harpoon tip geometries penetrate specific materials best? How does the harpoon mass and cross section affect penetration? The ballista allows us to safely collect this data and use it to size the cannon that will be used on the actual mission.”

There is no computer modeling available for the tasks the harpoon needs to perform, so Wegel’s team is going about their research with what basically amounts to old fashioned trial-and-error testing. Their basic piece of equipment is the “ballista” mentioned above by Wegel, a crossbow type of device that propels the harpoon into test surfaces with great force using a medieval-era invention, the leaf spring.

The typical leaf spring is a long, narrow strip of steel, laminated with progressively shorter strips and curved into a bow. They were originally used as suspension systems in carts and carriages, and variations are still in use today for more advanced vehicles.

For that matter, the earliest known crossbows date back at least to the 4th century B.C.

NASA scientists are particularly interested in collecting comet samples because they are searching for more evidence to support the theory that the elemental molecules that form life as we know it today were delivered to a barren Earth.

The ready-made “kit” theory of the origins of life posits that comets and meteorites carrying amino acids may have been the key catalyst for life on Earth. Amino acids have already been detected in several meteorites as well as in samples from comet Wild 2.

The Wild 2 samples consist of floating dust collected on a fly-by during NASA’s Stardust mission. The new harpoon concept would enable NASA to dig deeper and collect samples from beneath the comet’s surface.

The research also has a more immediately practical aim, which is to develop a system for forestalling a catastrophic hit by a comet or meteorite, without setting off an explosion that would rain debris across the Earth.