Thinking with their heads and their stomachs, MIT scientists have been hard at work developing a means to cut down on rotten produce. They have developed a cheap electronic sensor built out of carbon nanotubes that can detect in real-time the ripeness of fruits and vegetables.

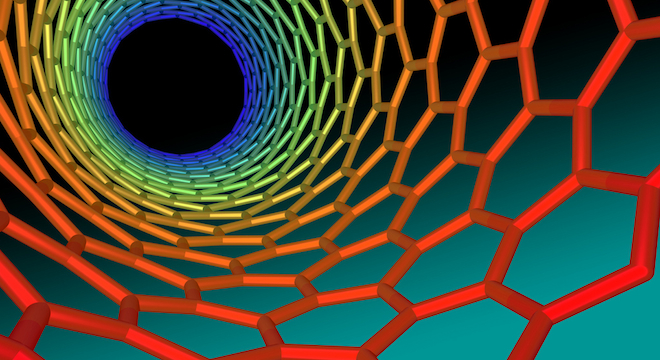

The tiny sensor was constructed using tens of thousands of nanotubes, sheets of carbon atoms rolled into cylinders, with added copper atoms, for a cost of about 25 cents, MIT News reported on Monday. With an added radio frequency identification chip, the total system’s cost would be about $1.00.

MIT’s sensor detects ripeness by monitoring the amount of ethylene, a gas that causes ripening and is secreted by some plants — such as apples and pears.

It works because the ethylene molecules bind to the copper atoms in the sensor, which slow down the flow of electrons through the carbon nanotubes.

By keeping track of just how slow the electron flow becomes, the sensor can determine with great accuracy just how ripe, or rotten, a box of fruit is at any given time, up to 0.5 parts per million in a conservative estimate, compared to other competing ripeness sensors on the market, which can only get down to about 50 parts per million.

MIT envisions that its sensors could be clipped on the edge of a crate of fruit in a supermarket or stand and checked occasionally.

“These sensors would be able to give an average level [of ethylene] for a box,” said MIT chemistry professor Timothy Swager, one of the scientists who led the development of the sensors, in a email to TPM.

“It is implicit here that there would be changes in how people made decisions in retail situations,” Swager told TPM. “This is an suggestion and exactly how the real world will make use of this is more complicated. However, local ethylene monitoring with inexpensive sensors will enable new ways to manage plants.”

Swager said that it took him and his students about a year to develop working sensors, the results of which have been published in a paper in the journal Angewandte Chemie.

The MIT team’s research was funded by the U.S. Army Office of Research. Swager explained the Army’s interest in the technology as being one of a more general interest in electrochemical sensors.

“They are interested in fundamental innovations in the creation of new types of chemical sensors,” Swager told TPM. “The basic science here could be applied to many types of problems relevant to the military.”

But as far as Swager and his colleagues are concerned, the benefits to produce merchants would be the most obvious. U.S. supermarkets lose 10 percent of their produce to spoilage annually, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.