TINA CASEY

Fame is a fleeting thing, and that goes double for the rapidly evolving world of nano-materials research. Scientists around the globe have spent several years highlighting the virtues of ultra-thin nano-material graphene following its surprise discovery in 2004, and now it seems that graphene is already being shoved out of the spotlight by the next big thing, a group of materials called graphynes.

Graphene is a sheet of a carbon alletrope that is only one atom thick but 200 times stronger than steel. Because of its superlative properties — it’s the lightest, thinnest, most electrically conductive and strongest material yet synthesized — it is a promising candidate for the next generation of small, lightweight, speedy electronic devices.

Graphene was only discovered a few years ago and researchers have yet to work out the kinks, which includes figuring out how to manufacture it on a commercial scale (using current technology, graphene can only be grown in small sheets).

Meanwhile, along comes graphynes. According to Belle Dumé at PhysicsWorld, a team of researchers at the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany has run computer models and found that the secret behind the “outstanding electronic properties,” previously thought unique to grapheme can actually be found in two-dimensional sheets of carbon atoms with different configurations.

That secret is a type of structure called “Dirac cones,” which sounds like something out of an old Saturday Night Live routine but actually refers to an “unusual relationship” that occurs at the point between a double cone-shaped feature in graphene. Electrons accelerate as they travel up the cone and according to Dumé:

“The result is that the electrons in graphene behave as though they are relativistic particles with no rest mass, and so can whiz through the material at extremely high speeds.”

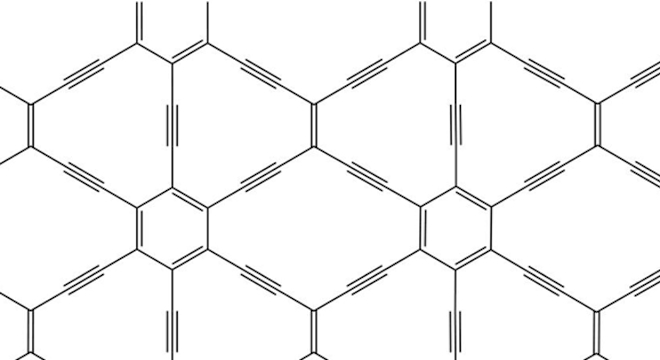

The carbon atoms in graphene are assembled in a distinctive hexagonal honeycomb or lattice-like pattern, and it was previously thought that only this structure could support Dirac cones.

The new breakthrough reveals that other two-dimensional carbon configurations can support Dirac cones. These new materials could possess new properties that graphene can only dream of.

One variant described by Dumé would be a symmetrical, rectangular configuration, in which electronic properties would depend on the direction of the current, something not seen in graphene.

Graphynes also have the capability of self-modulating their electronic properties, which means that they could be used as semiconductors practically as-is rather than requiring external “doping.”

Despite the promising career of graphynes, graphene is not ready for its last curtain call, and researchers are still digging into its unusual properties. For example, a team at the University of Manchester in the UK, where graphene was first synthesized, recently discovered that graphene could act as an excellent super-distiller of alcohol.

In July 2011, a research team led by grad student David Siegel of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory studied the Dirac cone behavior in graphene and reported that:

“Graphene is not a semiconductor, not an insulator, and not a metal. It’s a special kind of semimetal, with electronic properties that are even more interesting than one might suspect at first glance.”

Researchers from Manchester University have also come up with a graphene variant called graphane, in which hydrogen atoms are attached to the carbon lattice in insulating layers to form a kind of nano-sandwich.

The result is a material with the advantages of graphene but with more promising potential for commercial scale production, assuming that sheets of graphane could be cut into nanoscale strips for use in electronic devices.

That would be a big turnabout for graphene since its humble beginnings, when the only way researchers could obtain it was by literally lifting a layer of carbon atoms off a chunk of carbon with sticky tape, much in the way kids used to copy frames of comic books on a wad of Silly Putty.