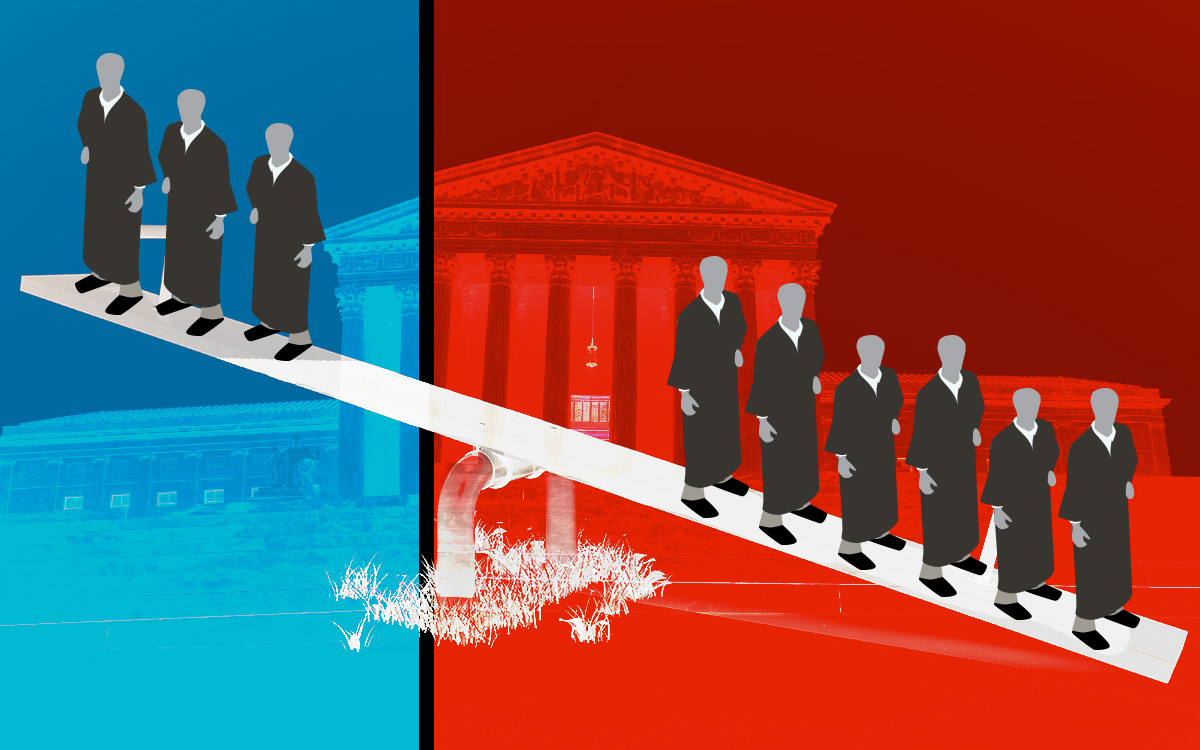

The Supreme Court conservatives, exuding the heady self-confidence of a team that knows it cannot lose, haven’t been coy about the jurisprudence they want to reshape or tear down.

Religious liberty, abortion, guns — the Court has recently taken up and dispensed with a whole swath of cases at astonishing speeds, often dramatically changing the bench’s long-held posture in relative silence through the shadow docket.

But perhaps on no topic has the Court telegraphed its intent more clearly than the administrative state, the power of federal agencies to regulate and make rules. The dry name belies a system absolutely critical to every corner of American life.

“If I want to dump chemical waste in a swamp, I’d prefer that the federal government not have power to regulate that,” Julian Davis Mortenson, professor at the University of Michigan Law School, told TPM. “If I want to pay people working in my factory a miserably tiny wage, or employ 12 year-olds, I’d rather the federal government not have the power to make a rule against that.”

The Court is now stocked with justices hungry to shift the power back in the direction of those nonregulatory interests. In doing so, they’ll really be shifting power to themselves.

“If the Supreme Court truly honored the rule of law and precedent, then they would acknowledge the power of the agencies that was granted to them by Congress in order to save our environment,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) told TPM of a recent illustrative case involving the Environmental Protection Agency. “But this is an extremist Supreme Court, so I’m very worried about the outcome.”

Because Congress is already paralyzed on critical issues, the prospect of a future in which the administrative state is rendered toothless is also a future in which unelected, conservative Justices become the arbiters of what the government can and can’t do. It’s a right-wing fantasy, cherished and developed for decades, come to life.

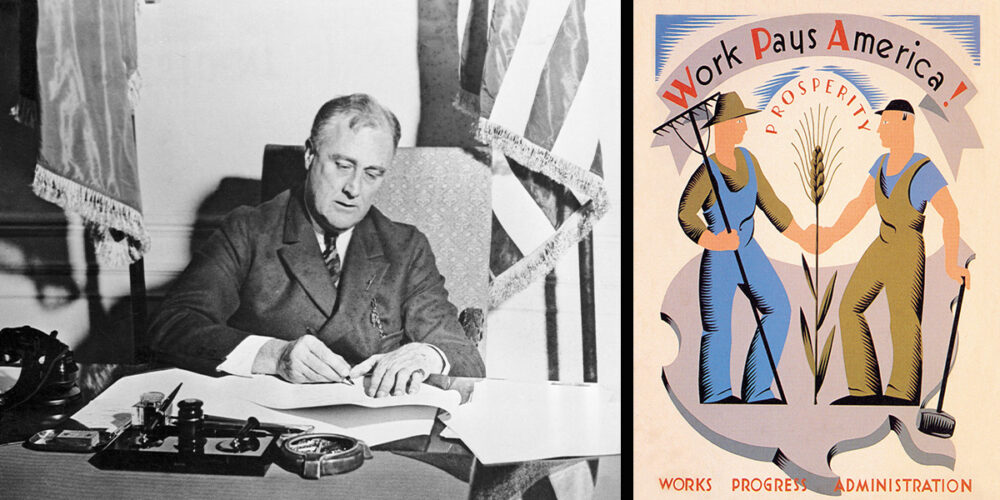

1930s: New Deal, New Doctrine

To understand how we got here, we need to travel back to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. The Court struck down some very broad provisions of the New Deal using something called the nondelegation doctrine — the idea that Congress cannot outsource its legislative powers to other entities.

But that movement was short-lived.

“There was a revolution in jurisprudence during the second half of the New Deal,” Mortenson said.

That change in thinking, helped along by retiring justices that were replaced by Roosevelt’s nominees, largely governed how the high Court continued to think until recently: that the courts will never be in a good position to answer questions about how much delegation is too much without relying on judges’ policy preferences.

It’s now been almost a century, and the Court has never again struck down a regulation based on the nondelegation doctrine.

Instead, courts for many years largely stuck to the same basic framework: Congress gives agencies power through laws it passes, and the experts who make up that agency are the best suited to interpret and implement those statutes. For example, if Congress tells the EPA in a statute to regulate pollution with the best technology available, EPA experts are tasked with translating that into specific rules for industries to follow.

Agencies have the expertise and nimbleness to pass regulations and make rules that Congress lacks. Today’s Congress, nearly inoperable thanks to the Senate filibuster and hyperpartisanship, can hardly muster the effort to pass a handful of laws every year. Imagine tasking the legislative branch with passing a new law every time an agency wants to tweak a regulation about factory protocols or carry out an affordable housing program — the vision dreamt of by nondelegation advocates.

Those advocates, some of whom currently sit on the Supreme Court, maintain that rulemaking through the agencies, nestled in the executive branch, is undemocratic: the officials who staff the agencies are elected by no one, after all.

It’s an argument cloaked in disingenuousness and a feigning of ignorance about how the government works. Even if you don’t buy the counter-argument that agencies are filled out by the President who is directly accountable to voters, it’s simply not the barely-functioning Congress that would become empowered by agencies losing authority — it’s the judicial branch, the least democratic of the three.

This skewed power balance is already on display. If agencies can’t be trusted to operate with some independence and Congress is unable to pass new laws governing what agencies can do or to clarify old ones, that leaves judges to decide the limits of agencies’ power.

1940s-1970s: Political Turbulence And Agency Growth

But all of that came later. As America moved deeper into the New Deal era and the nondelegation doctrine fell out of favor, there remained some lingering questions about the power agencies should have. The American Bar Association, for one, had some concerns.

“There was a push to pass a statute regularizing and constraining New Deal agencies,” Gillian Metzger, professor of constitutional law at Columbia Law School, told TPM.

Roosevelt vetoed the first product of that effort, but directed his attorney general to study the question. From that emerged the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946, still the statute governing how agencies develop and issue regulations.

During World War II, New Deal agencies expanded significantly and new ones were created to convert the peacetime economy to one able to meet the demands of war.

“Because of World War II and the Cold War, there was extra legitimacy given to the administrative state since it was considered part of the security state as well,” Jon Michaels, professor at UCLA School of Law, said. Without World War II, “the administrative state would probably be more parsimonious since we don’t care as much about protecting the rights of children or anything like that.”

In the ‘60s, the backlash to the administrative state took a new form.

Milton Friedman and the Chicago School of economics championed a hands-off government, developing a school of thought that would later influence President Ronald Reagan.

In the political sphere, President Lyndon Johnson was dramatically expanding the social safety net with his Great Society, a set of domestic programs meant to eliminate poverty and racial injustice.

“He was doing things that Roosevelt didn’t do to actually cover Black people,” Michaels said. “All of the sudden, that turned Roosevelt Democrats into Archie Bunker — Nixon Republicans — and the New Deal coalition broke down.”

The tumult of the Carter administration, bogged down by persistent stagflation, helped solidify the thinking in conservative corners that big government had failed.

At the same time these seeds of thought were being planted on the right, agencies experienced a period of fecund growth as the public and government embraced a series of movements aimed at enhancing people’s rights and quality of life.

“The ‘60s and ‘70s saw the consumer movement, the environmental movement, the women’s movement, the civil rights movement — all these things together built up support in Congress to create new agencies and give them new authority,” Peter Shane, chair in law at Ohio State University, said.

Think the EPA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the Department of Energy.

Amid the agency growth and dueling conservative opposition to big and interventionist government, the courts remained stable and consistent in granting agency authority. It would be another 30–40 years before nascent ideas about the danger of agencies and regulation would come to fruition.

1980s: The Reagan Revolution

The lessons of Friedman, of the anti-Great Society crusaders, of the disillusioned New Dealers had taken hold of a new generation of legal minds. It included then-Associate Counsel to the President John Roberts and then-Assistant Education Secretary Clarence Thomas.

Welcome to the era of small government. The motto: “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.” Deregulation, narrowing the government’s footprint, attacking the “welfare” state – these were the fashions of the day.

“It’s not surprising that this hard push occurred in the 80s because in the late 60s and 70s, Congress began to authorize federal agencies to engage in much more ambitious rulemaking activity than had previously been the case,” Shane said.

While anti-regulation ideas took seed in the administration, an outside forum cropped up where they could incubate: the Federalist Society.

Founded by law students disillusioned by what they perceived as an over-liberal slant in the preeminent law schools in 1982, it grew explosively into a national organization where those on the right could debate and develop legal theories to bring about the deregulatory, small government vision they had for the world. Nondelegation was resurrected, originalism gained speed and support.

It also became a mill for churning out judicial nominees who reliably hewed to that conservative mindset.

The full power of this double-barrelled force took years to be realized, though it has everything to do with where we are now.

“Conservative jurists actually supported executive discretion because they wanted to give Reagan a free hand,” Blake Emerson, assistant professor at UCLA School of Law, said. “Scalia came out of that tradition. But the policy dynamic shifts when you have progressive president trying to use agency power.”

Despite the political backlash to big government and the embrace of winnowing it down, the court actually expanded agency authority in the height of the Reagan era. Then, it was still connected to the power of the executive — something conservatives, confident in the idea that one of their own would surely frequently occupy the White House, were happy to protect.

Early 2010s: Obama In The Crosshairs

Then onto the scene came the perfect target: President Barack Obama, with his liberal ideals and a Congress often stalemated by Republicans open about their intent to stymy his agenda by whatever means necessary. The rise of the Tea Party bolstered this zero sum strategy.

“The approach was absolute opposition: ‘We want to see a failed presidency, let’s see how we can do that,’” Emerson said. “That message was received by a lot of jurists. The inclination to revive some very powerful constitutional tools as part of that was strong.”

The momentum was there. The development of ideas to achieve deregulatory ends — nondelegation and another theory called the “major questions doctrine” that holds courts should not defer to agency interpretations when the rules have implications of “vast economic or political significance” — was chugging along. But the Court wasn’t yet peopled with enough justices that bought into this worldview.

Even while Scalia started to sour on his initial defense of agency power, other conservative justices like Anthony Kennedy still hewed to the old-school model of being philosophically pro-business, but still largely accepting of the legitimacy of agency rule-making.

But the cracks were starting to show, even then.

In a 2010 case called Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, the conservative majority wrote that “the growth of the Executive Branch, which now wields vast power and touches almost every aspect of daily life, heightens the concern that it may slip from the Executive’s control, and thus from that of the people.”

In City of Arlington v. FCC in 2013, where Scalia upheld Chevron deference, a doctrine that says agencies are entitled to their reasonable interpretations when Congress’ statutes are vague, Roberts gave a clue to where the Court was headed in his dissent.

“It would be a bit much to describe the result as ‘the very definition of tyranny,’ but the danger posed by the growing power of the administrative state cannot be dismissed,” Roberts wrote.

“He wrote that he doesn’t think Chevron should apply unless Congress specifically delegated authority to an agency, which is not the broad grants of regulatory authority that you often see in statutes,” Jeffrey Lubbers, professor of practice in administrative law at American University’s law school, told TPM. “Those grants have been read broadly by the Court in the past, and it was an indication that they may start cutting back.”

In Burwell v. King, a massive Affordable Care Act case in 2014 and 2015, Roberts appended a asterisk to the understanding of agency deference that the Court had been abiding by for so long, saying that trusting the agency’s interpretation should not be considered appropriate in questions of major economic and social significance — a high profile invocation of the major questions doctrine.

While Roberts did help uphold the statute in the case, it was a massive step forward for the champions of weak government.

“It gives authority to the courts to decide whether they feel a question is important enough to treat it thus, based on who knows what,” Shane said, calling the implications of Roberts’ perspective “jaw-dropping.”

“Secondly, one of the reasons Congress delegates questions to agencies to resolve is precisely to deal with unanticipated problems and unforeseen developments,” he added.

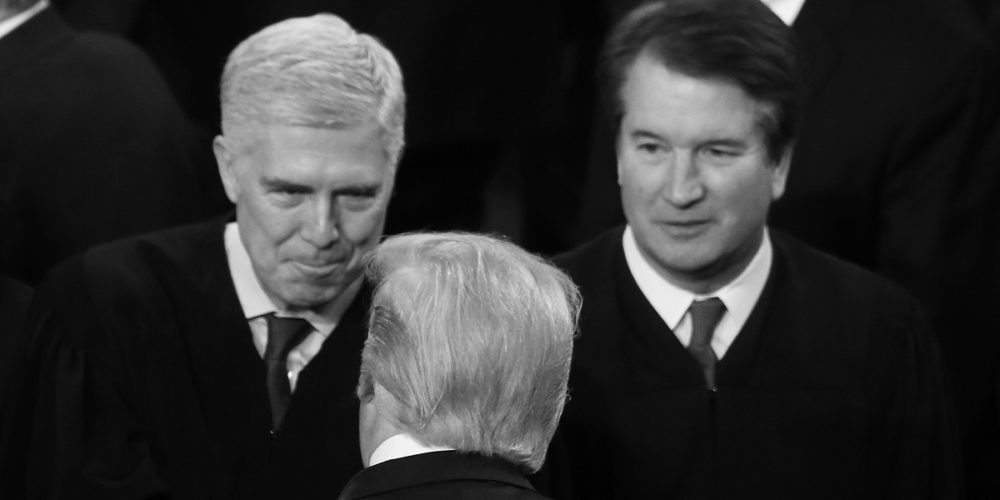

Late 2010s: The Dream Court

With the election of President Donald Trump in 2016, the vision dreamt up in Federalist Society conferences and Reagan administration cocktail parties was within reach.

Steve Bannon, then still White House chief strategist and mastermind behind Trump’s rise, used his first public debut in 2017 to promise a yearslong crusade for the “deconstruction of the administrative state.”

Trump had promised during the campaign to fill any Supreme Court vacancy on his watch with a Federalist Society-approved candidate, all but sounding the death knell for agency power.

He got one vacancy thanks to Mitch McConnell’s theft of a seat that should have been Obama’s to fill — and then he got two more. It was a changing of the guard.

In Gundy v. United States in 2019, you can almost taste the conservative excitement. Justice Neil Gorsuch writes expansively on his view that the Court is entitled to second guess any congressional statute it thinks went too far.

“To leave this aspect of the constitutional structure alone undefended would serve only to accelerate the flight of power from the legislative to the executive branch, turning the latter into a vortex of authority that was constitutionally reserved for the people’s representatives in order to protect their liberties,” he wrote of agency deference.

But the anti-regulation crusade would have to wait a little bit longer. Justice Brett Kavanaugh was not yet on the court, and Alito switched to vote with the liberals — explicitly adding that he’d want to revisit these questions when they have a full bench.

2020s: A Vision Realized

Now the court has a conservative supermajority. It’s already smacked down a Biden administration mandate-or-test rule in a decision experts characterized as stunning, taken against the decades of Court behavior in agency power cases.

“The Court is absolutely comfortable second-guessing every single thing the government did in a compressed time frame during a pandemic,” Mortenson said. “Over the course of the 20th century, that’s absolutely gobsmacking. There is a full-throated commitment to instantiating preference for a narrower government dressed up in legal doctrines.”

Upcoming cases will give the Court more opportunity to cut President Joe Biden’s agencies off at the knees. They heard one this week in particular, West Virginia v. EPA, against the administration’s wishes as it concerns a now defunct rule the administration has no interest in enforcing. Experts see it as a sign of the Court’s eagerness for any opening to decimate the EPA’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions.

The Court, with its relatively young majority, is showing no inclination towards restraint. The only thing that can stop it now is its own hubris.

“This is the first time since the New Deal that legal academics are talking seriously about the need to expand the Court. That’s a legitimate problem, if not a crisis for the Court,” Emerson said. “When there is such a big gap between the median voter in this country and the Supreme Court, the Court is putting itself at some risk.”

Agencies have the expertise and nimbleness to pass regulations and make rules that Congress lacks. Today’s Congress, nearly inoperable thanks to the Senate filibuster and hyperpartisanship, can hardly muster the effort to pass a handful of laws every year. Imagine tasking the legislative branch with passing a new law every time an agency wants to tweak a regulation about factory protocols or carry out an affordable housing program — the vision dreamt of by nondelegation advocates.

Those advocates, some of whom currently sit on the Supreme Court, maintain that rulemaking through the agencies, nestled in the executive branch, is undemocratic: the officials who staff the agencies are elected by no one, after all.

One might want to inform SCOTUS new and old right-wingers, that they are not elected either.