This behind the scenes account of the pivotal 2020 Iowa caucus is adapted from one chapter of the new book The Truce: Progressives, Centrists and the Future of the Democratic Party, by Hunter Walker and Luppe B. Luppen. The book is based on over two years of reporting and interviews with key figures at every level of progressive politics to bring you a definitive history of a half-decade of upheaval in the Democratic Party along with unparalleled insights into what’s coming next for Joe Biden and the left. The Truce is available for pre-order now and will be released on January 23, 2024.

When the night of the Iowa caucus arrived, Bernie Sanders had every reason to expect good news. He was set to win.

The Vermont senator was deep in his election-night ritual, with his lanky, crooked frame stalking around a hotel suite filled with his family and Faiz Shakir, his campaign manager. He peppered his people for scraps of information about the turnout.

“How are we doing?” Sanders asked, insistently and incessantly. “How are we winning?”

But the answers never came. Instead, everything went sideways.

Iowa was the beginning of the end for Bernie Sanders. A night where he imagined triumph ended in something even worse than defeat.

It’s almost impossible to overstate how much the Hawkeye State meant to Bernie Sanders and his campaign at this moment. As Shakir put it months later, they had it “all plotted out” after a win in the traditional first caucus.

But that night, as Sanders paced in the Des Moines Holiday Inn, waves of bad news rolled in. Across town, in a squat, redbrick building that served as the nerve center for his campaign leadership, senior aides were panicking.

“There was chaos. Everyone was freaking out,” Sanders’s deputy campaign manager, Arianna Jones, recounted. “Bernie was pissed too.”

Back at the hotel suite, Shakir said he found the candidate sitting with his hands at his temples and a thousand-yard stare glaring from behind his glasses.

“The only thing I remember is towards the end of the night . . . how upset—like really upset—he was,” Shakir said of Sanders. The candidate grimaced with a mixture of what Shakir described as searing pain and “seething anger.”

“We were just despondent about the situation,” Shakir said. “He felt robbed.”

Sanders’s first presidential race, in 2016, was a bitter battle against Hillary Clinton, whose hundred-million-dollar fortune garnered from the global conference circuit and connections accrued over decades as First Lady, senator from New York, and secretary of state made her the living embodiment of the elite, centrist mainstream Sanders despised.

Four years later, Sanders had gone from a relatively obscure independent to a powerful senator with supporters in Congress, in city and state capitals around the country, and, with Clinton swept aside by Donald Trump, even in the party leadership. Sanders was starting the 2020 race in a far stronger position, and a win in Iowa would establish enormous momentum out of the gate.

Compared to the rest of the field, Sanders had the biggest team in Iowa and the most money in his war chest. Next up was New Hampshire, which Sanders had won in 2016, and then Nevada, where his robust operation had connected with the state’s large Latino population. Based on the known poll numbers, a streak of three early state victories seemed almost inevitable. And, in a primary system where momentum is the coin of the realm, a trio of early wins could be enough to wrap up the Democratic nomination.

Sanders’s strategy—and route to victory—made sense, but it all depended on Iowa. And on that night, the state delivered Sanders and his staff an almost unthinkable outcome.

“Devastating is an understatement,” Shakir, the campaign manager, said when asked about what happened next.

Iowa occupies a peculiar place in American politics. Its caucus has had primacy in the nominating process since 1972. That special status has afforded voters in the state, who are less than 1 percent of the US population, an immense degree of influence over the last twelve presidential races.

Along with a special place on the primary calendar, Iowa has had an eccentric voting system. Caucuses are not simple votes. The Democrats’ process has involved people gathering at an appointed hour in over 1,600 sites around the state including churches, community centers, at least one meatpacker’s union hall, and a Shriners Temple.

Traditionally, when the action starts, there are speeches and the crowd separates into groups supporting each candidate. It’s like a high-stakes version of musical chairs. Then, administrators take a headcount. Any contingent that falls below a designated viability threshold is disbanded. Supporters of the other candidates then lobby the members of the losing factions to join their side before another count is taken. The process can take hours. Ties are sometimes decided with a coin flip. It’s a messy, imprecise system.

In years past, the Iowa Democratic Party did not announce the raw vote totals. Instead, for public consumption on caucus night, it solely reported a metric called “state delegate equivalents,” which was calculated based on the location of the site, turnout in recent elections, and lastly, the actual vote totals captured by the two headcounts. Those figures were then filtered through a separate formula to determine how many of Iowa’s delegates will back a given candidate at the Democratic National Convention.

Those elaborate calculations include multiple points where numbers must be rounded, which pulls the state delegate equivalent figure further away from the raw vote total. Campaigns had previously reported discrepancies between the official results and their data from caucus sites, raising questions about how the state party volunteers executed the math. Small mistakes could make a major difference. In 2012, for example, the Republican caucus came down to one-tenth of a state delegate equivalent.

In 2016, Sanders’s loss to Clinton was tight as well—one-quarter of a percentage point in the state delegate equivalents. Sanders’s campaign compiled their own data from the caucus sites that year. Based on their internal numbers, some Sanders aides were convinced he won the popular vote and possibly the delegate metric as well. However, since the state party didn’t report the vote totals, there was no way to check.

With his strong showing and Clinton’s ultimate loss to Trump in 2016, Sanders earned a degree of pull behind the scenes. He used it to chip away at some of the structures that preserved backroom influence and, he was convinced, had cost him the White House, including the black box that previously surrounded the raw count. In 2020, after a push from Sanders and his allies, the Iowa Democratic Party had agreed to announce the number of actual votes along with the state delegate equivalents.

Some observers warned that this could lead to a mess where one candidate was victorious in the popular vote and another won more delegate equivalents. Of course, such messes were equally possible in previous election years. There had just been no way to prove it.

There was one other wrinkle in 2020. Along with reporting a whole new set of numbers, Iowa’s Democrats launched an app to transmit the results from the more than 1,600 caucus sites across the state. It was designed by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs with deep party ties, and it crashed spectacularly.

As it became apparent something had gone very wrong with the caucus, an explosive battle erupted among Sanders’s staff as they scrambled to salvage the moment that was supposed to catapult him to victory. Sanders’s former senior adviser Chuck Rocha was one of many who remembered the debacle vividly—and painfully.

“I was in Iowa that night when all hell broke loose,” Rocha said.

In an East Texas drawl peppered with colorful euphemisms, he offered his assessment of the highs and lows of caucus night in Iowa: “There’s good. That’s about twenty percent,” Rocha said. “Then there’s eighty percent that is the most horrific thing I’ve ever lived through in my life.”

That night, Sanders’s senior team was mostly in the war room. Other staff gathered at the ballroom at the Des Moines airport Holiday Inn for the party. Ostensibly the election-night reception is a place for supporters to celebrate a victory or commiserate after a loss. But, as with so many other things in politics, the real purpose was to put on a show for the national media camped out in the back of the room.

These early primary contests are about “The Narrative” at least as much as the actual results. As results come in, particularly in a crowded race, campaigns begin jockeying with each other and the networks to secure precious on-air minutes to amplify their message about the contest. Ideally, a candidate is able to ice out their competitors and get on air early to claim some measure of victory.

“I was in Iowa that night when all hell broke loose.”

Counting normally begins at 7 p.m. at most sites around the states. Caucus results typically start pouring in an hour or so later. With no numbers posting and party officials ignoring requests for information, Shakir began to realize the evening was becoming, as he put it—bowdlerizing himself—“kind of a cluster.”

“And then it just, clearly, it turns out to be like a much more massive cluster than we ever could have imagined,” Shakir said.

The other top Sanders staffers were mostly camped out in the downtown war room taking in reports from the field, putting out fires, and fielding Sanders’s constant requests for information. Often, the man on the other end of the line was Jeff Weaver. Sanders’s calls took on a panicked urgency as the hours dragged on.

“Jeff, why aren’t there numbers yet?” he implored.

A staunch loyalist since Sanders was mayor of Burlington, Vermont, Weaver had been in charge of Bernie’s war rooms for decades. The laconic native of Vermont’s Northern woods was a former Marine with a white beard and a dry sense of humor. When discussing his boss, Weaver resorts to clipped understatement—if you can get him to talk at all.

Weaver’s ability to appear unruffled under fire would be sorely tested as the caucus night deteriorated.

Each time Sanders called, Weaver would offer a matter-of-fact reply, giving Sanders the information he had—which wasn’t much.

Asked about his experience on that night, Weaver offered a typically spartan assessment, saying it was his job to “manage any problems” that came up.

“And, you know, the problems that occurred,” said Weaver, “I don’t think any of us could have anticipated.”

Others who were in the war room remembered the evening in far starker terms.

“Things started to go to shit,” Arianna Jones, the deputy campaign manager, recalled. “The vote wasn’t coming in.”

Sanders’s issues in the caucus began well before the Iowa Democratic Party’s app crashed, and many stemmed from his long-standing frustration with the Democratic Party itself.

The candidate’s 2020 launch speech framed his campaign as dedicated to fighting the “powerful special interests who control so much of our economic and political life.” Such “special interests” included the supposedly liberal party, which he felt protected the advantages enjoyed by the elites through mechanisms designed to frustrate the will of the voters, like the arcane superdelegate system that allowed insiders to pick presidential nominees at the national convention. The Iowa caucus, with its complex counting system and weighted delegates, was another party apparatus that thwarted majority rule.

Sanders and Weaver had little patience for the complicated formula and how it could weigh votes from rural caucus sites more heavily than the bigger cities and college towns. They were confident the popular vote numbers would make him a clear winner now that the totals would be public.

The disdain for the arcane delegate math set the stage for a dangerously close night. While Sanders had fixated on the popular vote, some of his staff feared that this had created an opening for a rival. Sanders would no doubt run up big margins in Iowa’s cities and college towns, but a competitor could outflank him in more sparsely populated corners of the state and earn a victory in the delegate count.

Indeed, in the weeks leading up to the caucus, one of his opponents, Pete Buttigieg, had gained in the polls with a barnstorming rural bus tour. With a crew cut, Rhodes Scholarship, and twinkling blue eyes, the former Naval intelligence officer was the fully evolved apex version of the typical, chipper Democratic staffer. Buttigieg’s position as the chief executive of South Bend, Indiana, earned him the nickname “Mayor Pete.”

Voters were charmed by Buttigieg. The first openly gay candidate to mount a serious primary bid, Buttigieg carved a clear lane for himself as a moderate alternative to Sanders. Mayor Pete leapt from relative obscurity to averaging just a few points behind Sanders—and at times leading the polls—in the weeks before the caucus.

Sanders also had his own strategies for exploiting the process in Iowa.

Matt Berg was an election lawyer whose official title was “director of delegates and ballot access” for Sanders’s campaign in 2020. A thin, soft-spoken man, Berg doesn’t come off as a political street fighter. However, his subdued nature belies his effectiveness. Berg’s ability to game various electoral systems was so significant that he was one of the only Sanders staffers Clinton brought on to her general election operation after their bitter primary fight in 2016.

Ahead of the caucus, Berg had a pet project. As part of its changes to the 2020 process, the Iowa Democratic Party created a remote caucus plan with sites around the country—and even abroad. Berg quickly realized there was “an edge to be gained” by focusing on those so-called satellite caucus sites. Worried the race was closer than the campaign realized, Berg went to Weaver.

“I realize the goal is to win Iowa by like five points, Jeff,” Berg said. “But, if Iowa is a one- or two-point race, this is one or two percentage points.”

Weaver let Berg hire an operative to find Sanders supporters from Iowa who lived out of state and could organize satellite caucuses in Sanders-friendly territory.

The first votes were cast in the former Soviet bloc at a satellite site in the living room of a freelance foreign policy journalist in Tbilisi, Georgia. It turned out that Iowa expats tended to like Bernie. All three voters there went for Sanders, netting him approximately one-one-hundredth of a percentage point of a state delegate equivalent. Berg’s plan had given Sanders a strong start to caucus night.

As the voting rolled westward past Europe and over the Atlantic, it was all going his way.

The voting at these early events concluded before the majority of the caucuses in Iowa began. There were no apparent issues with the results. When the main event began, the party’s app cratered and a backup phone system became jammed. At this point, the Iowa caucus broke down.

Sanders’s official headquarters was largely deserted. Local staff were out working at caucus sites and the main area of the office was strewn with signs and other election detritus.

Inside, tables were set up facing a television to watch the coverage. About a dozen senior aides filed in and out throughout the night. The caucus was well underway and it was obvious things were not going as planned.

Berg had been texting with Patrice Taylor, director of party affairs for the Democratic National Committee, and Dave Huynh, who is better known in political circles as “Delegate Dave.” Huynh was Berg’s counterpart working ballot access for Joe Biden’s campaign. Berg and the other aides initially were “cracking jokes at each other.”

As one hour stretched into two, the text thread turned serious.

“The app crashed didn’t it?” Berg asked the DNC official.

There was no answer. According to Berg, Taylor “went dead.”

As the evening wore on, the Iowa Democratic Party leadership finally announced it would be having a conference call with all of the campaigns.

“That’s when we knew that it was, like, bad,” Berg said.

On that call, the officials admitted the party’s own app had failed. Nevertheless, the state party insisted the integrity of the results would not be impacted and that they would ultimately be able to declare a winner after recovering all the hand-counted results from the caucus sites. The campaign staffers were indignant and began to vent their frustrations. But the party leadership hung up. There would be no final results on caucus night.

That delay was critical. Tim Tagaris—Sanders’s fundraiser—was waiting for the final numbers to send out a mass email requesting donations. Every hour that fundraising message didn’t go out meant less cash would come in. It was agony.

“He knows that the later he sends out his fundraising email, the less money he raises,” Berg said. “The life is slowly draining out of Tim Tagaris as the night wears on.”

And the money was just one of the problems generated by the lack of a definitive result. There was also the question of The Narrative—and that led to a full-scale blowup in Sanders’s war room.

Ben Tulchin, the campaign’s pollster and one of its key strategists, was adamant Sanders should simply declare victory. The Iowa Democratic Party wasn’t the only one whose technology had failed. A broken app and issues with shared spreadsheets had prevented many of Sanders’ teams in the field from reporting in their numbers. Nevertheless, based on the partial data the campaign had received, they were certain Sanders was in a strong position—particularly when it came to the popular vote—and Buttigieg was in second. Tulchin wanted Sanders to get on stage, go on air, and claim a win before Buttigieg might do the same.

With official results not only inconclusive but wholly unavailable, Weaver was insistent that Sanders refrain from making what might be an inaccurate victory speech. When he called into the war room, Sanders was also reluctant to plant a triumphant flag on the night without official numbers. Residual trauma from 2016, when many establishment Democrats accused Sanders of being a bad actor, weighed on him.

Weaver was on the same page with Shakir and Sanders. He told an increasingly agitated Tulchin that, in the absence of official results, a victory speech was not happening.

As the caucus fiasco unspooled, the pollster was apoplectic. Weaver eventually lost his patience. His standard war-room calm shattered.

“I’ve never in my life seen Jeff Weaver scream at someone the way he screamed at Ben Tulchin that night,” Arianna Jones, the deputy campaign manager, said.

Bald head beet red, Weaver ordered Tulchin out of the room.

“At that point Ben took a step back like he was going to exit the room and sort of stood in the doorway but then continued to argue his points,” Berg said. “There was a lot of cursing and name-calling going on.”

Weaver got out of his chair. “Get out of the room now!” he bellowed.

“Ben’s flight instinct kicked in,” said Berg. “I think Ben thought Jeff was going to shove him through the door.”

Weaver, ever the Sanders loyalist, offered a decidedly sparse assessment of the shouting match. “It was fine,” Weaver said. “He’s excitable.”

Excitable or not, Tulchin had a point. Buttigieg ultimately seized on the exact stratagem Tulchin had envisioned.

“We knew that we needed to meet reporters’ deadlines for the morning,” said Lis Smith, Buttigieg’s campaign manager, in an interview. “We also had to make a plane to New Hampshire because we had a full day of campaign events in New Hampshire the next day starting in the early morning, and so we had to get on that plane. … And we did want that visual for the next morning, and for newspapers, of Pete in front of a throng of supporters claiming—not claiming victory, but claiming . . . a strong showing.”

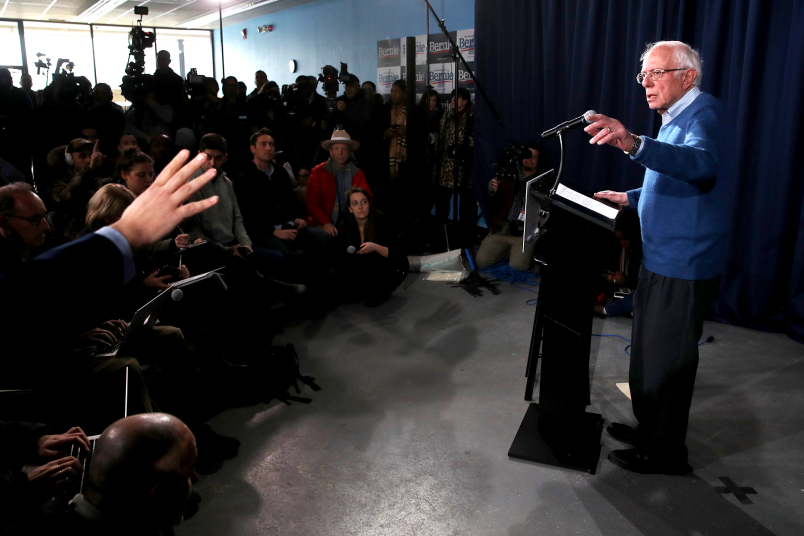

Shortly before eleven, Sanders took the stage at the campaign’s election-night party. As he approached the microphone, he quickly pumped his fist before taking a deep, frustrated breath and biting the inside of his lip. He stared down at the podium and gripped its sides for a moment before looking up to survey the crowd. Seeing the faithful gave Sanders a boost. He broke into a genuine smile.

“I imagine, I have a strong feeling that, at some point, the results will be announced,” Sanders said, dragging out each word in exasperation. “And when those results are announced I have a good feeling we’re going to be doing very, very well here in Iowa.”

Buttigieg — who had detailed numbers from his own team — was far less circumspect. After Sanders spoke, he took to Twitter and declared, “By all indications, we are going on to New Hampshire victorious.” Soon after, on stage at his own event, Buttigieg reiterated his claim.

Smith pointed out that Buttigieg had used artful language, saying he was going to “emerge victorious,” which the campaign felt more comfortable defending, even though they weren’t sure whether Buttigieg would come out ahead of Sanders or not.

They were shaping The Narrative.

“We didn’t claim outright victory . . . but, by any standard, the fact the . . . thirty-eight-year-old openly gay mayor of a town of 100,000 people was either in first or really close second place, that’s victorious in anyone’s book,” Smith said.

Sanders didn’t watch Buttigieg’s speech.

Questions remained about every aspect of the actual result.

“We get robbed of the opportunity to say that we won and we get robbed of the opportunity to stick daggers into the Biden campaign.”

While some news outlets followed the state party’s lead and declared Buttigieg the winner, the New York Times, the Associated Press, and others declined to name a victor due to issues with the party’s underlying data. The Democratic National Committee and the state party would proceed to battle in a blame game that went on for months.

Even more than Buttigieg, the aspect of the fiasco that truly worried Sanders’s team was the way coverage of the chaos distracted from the fact Biden, once a front-runner, finished a dismal fourth place. In hindsight, it was the first of many strokes of luck for Biden.

“The person it saved was Joe Biden,” Tagaris said. “Just spared him from coverage of what should have been just an absolute, unmitigated disaster of a result.”

Shakir, the campaign manager, agreed that losing focus on Biden’s poor showing cost Sanders. “We get robbed of the opportunity to say that we won and we get robbed of the opportunity to stick daggers into the Biden campaign.”

Sanders’s Iowa implosion played a pivotal part in Biden’s ultimate ascendancy to the presidency. But Sanders still ended up getting his victory in the Hawkeye State—technically.

Though the party’s official results were questionable, they still dictated the makeup of Iowa’s delegation to the Democratic National Convention, which took place six months after the caucus. The razor-thin lead the official results gave Buttigieg meant he would get two more delegates than Sanders on the floor of the party’s nominating convention. Sanders and his team disputed one of these delegates and argued he earned the same number as Buttigieg in Iowa.

As Biden secured the Democratic nomination, Sanders was his sole remaining challenger. The pair took pains to avoid a reprise of the last election’s infighting, which included Sanders supporters staging protests on the floor of the quadrennial convention. This time, Sanders quickly and unambiguously endorsed. And Biden created a series of unity task forces designed to give Sanders and his allies input on policy. Their teams held talks ironing out every aspect of the convention.

Those calls found Berg back on the phone with “Delegate Dave.” During negotiations over a separate issue, Berg decided to ask for the disputed Iowa delegate. If Berg could pull this off, Sanders would have the same number of Iowa delegates as Buttigieg to go with his popular vote victory.

In other words, Berg was trying to belatedly win (or at least tie) the caucus for Sanders with the exact kind of backroom maneuvering the candidate had always abhorred. It worked.

“I gave him something that he wanted that I didn’t want to give up. And I said, ‘I’ll give this to you. If you give me my statewide delegates in Iowa,” Berg said of his talks with Dave, adding, “I wasn’t even fully serious about it. It was kind of a joke, but he gave it to me, so I took it.”

The caucus came to an end on that call. There was finally a result.

Adapted from The Truce: Progressives, Centrists, and the Future of the Democratic Party by Hunter Walker and Luppe B. Luppen. Copyright © 2024 by Hunter Walker and Luppe B. Luppen. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Great article. Bernie was robbed in Iowa, twice. He was too polite to say so in public. But the narrative was critical, everybody had to see him as a candidate who could win the Presidency.

The fiasco does seem to be the straw that broke the camel’s back for the Democratic Party regarding the Iowa Caucus. The DNC has pushed Iowa (and New Hampshire) back in line (though NH seems to be intent on defying that since they wrote it into state law that they have to be the first primary). But it does bring states with more diverse populations to the fore and while it won’t matter much for 2024 with Biden running practically unopposed, we’ll have to see what the states do in 2028 when the primary is liable to be more open (depending on how popular Kamala Harris is to be the nominee).

Caucuses are just the worst.

Both New Hampshire and Iowa have benefited greatly from their nominating contests being the first. For example it is my understanding that it is the only reason we put corn ethanol in our gas as it may take more energy to make then is saved.

The problem for Democrats is that neither state is representative of the Democratic base. However, there is risk in saying that as New Hampshire that once never voted for Democrats has the last 5 presidential elections and Iowa that used to vote for Democrats seems to now be solidly Republican.

But the point is neither state is truly reflective of the nation and so their having an oversized influence on who is president should be ended.

One other thing, something I read about the Republican debate last night, that I did not watch, pretty much sums up what appears to have happened:

They are. In the 2016 Dem primary my state WA was still a caucus state. I knew my very liberal small town was going to have a caucus where Bernie supporters would just shout down anyone else, so I didn’t bother going. And sure enough, Bernie took the state over Hillary in the caucus by a whopping 73% to 27%.

For the 2020 Dem primary, WA had moved to a conventional balloted primary. Biden beat Bernie by a slim margin of 38% to 37% with Warren and Bloomberg in the single digits. Warren might have pulled a few votes from Bernie, but that 37% was a truer reflection of his support in the state, which wasn’t reflected in the earlier caucus system where he just had the most enthusiastic and fired-up supporters.