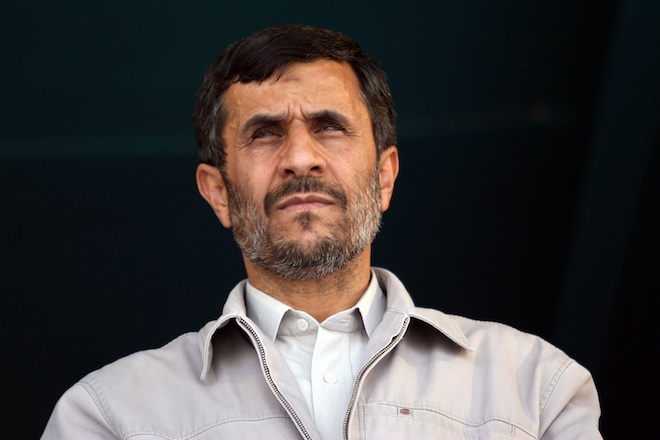

Mitt Romney called for the indictment of Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad for “genocide incitation” at Monday’s debate, a strategy his top adviser suggested might actually result in his arrest.

This wasn’t the first time the “indict Ahmedinejad” idea has been floated by a politician. In 2007, a bipartisan group of 103 House member co-sponsored a resolution demanding similar charges against Ahmadinejad. The movement grew out of Ahmadinejad’s inflammatory rhetoric against Israel, most notably a speech in which he reportedly said the Jewish state should be “wiped off the map” (although the translation later proved to be a point of contention).

So how would this plan to convince global prosecutors to indict Ahmadinejad work in theory? And is there even the slightest chance of applying it in practice?

According to UC-Irvine Law Professor David Kaye, a State Department veteran and expert in international law, there is at least some precedent in the International Criminal Court upon which the United States could theoretically help to build a case. As Romney alluded to in the debate, the ICC does recognize “incitement” as a legitimate charge under the Genocide Convention. In the 1990s, Rwandan politician Jean-Paul Akayesu was arrested, tried, and convicted by the UN International Criminal Tribunal for “direct and public incitement to commit genocide” among other crimes.

While the US does not belong to the ICC themselves, that doesn’t disqualify them from getting involved. The Bush and Obama administrations have both taken an active role in helping build cases against human rights offenders.

That doesn’t mean it would be easy. The first big hurdle is getting Ahmadinejad’s case before the ICC at all. Since Iran does not belong to the ICC, any investigation would have to be approved by the UN Security Council, where Russia and China have veto power. Neither country seems too likely to approve of the idea and Romney has pledged to take a harder diplomatic line against both of them on the campaign trail. There’s actually a relevant test case going on at the Security Council right now. Kaye noted that efforts to refer the ongoing conflict in Syria, where government forces are accused of horrifying war crimes, to the ICC have been stymied by veto threats.

“The Russians and Chinese are very clearly not going to allow a referral of Syria to go through the ICC right now either,” he said. “So it’s difficult to imagine the kind of universe in which there’s an actual referral of Iran to the council.”

Even then, the UN Security Council would not have the authority to refer Ahmadinejad himself to the ICC, only call for an investigation into the broader situation in Iran. The Rwanda charges were tied to widespread, tangible ethnic violence that killed hundreds of thousands of people, making for a clearer case. It would be much harder to argue Ahmadinejad’s quotes meet the same threshold with no ongoing genocide.

But let’s grant Romney’s assumption and imagine that Russia and China side with the United States and that the ICC decides on making Ahmadinejad a test case for a broader definition of the law. The court issues an arrest warrant for Ahmadinejad to stand trial. Provlem solved?

Not really, since arresting Ahmadinejad is a lot easier said than done. Iranian officials are less than likely to turn their sitting president over to a court they don’t even recognize and the UN’s peacekeeping force is limited to peacekeeping. So short of a NATO invasion, there’s not much more the United States can do than wait for him to show up in an ICC member state. That’s the problem facing the international community right now with Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, who remains comfortably in power despite facing an arrest warrant from the ICC since 2009. And there’s no guarantee that ICC countries will actually follow through on an arrest if given the opportunity. Bashir traveled to ICC signatory Chad in 2010 and left without incident, much to the consternation of human rights advocates.

Kaye said these kinds of difficulties are generally considered the “Achilles heel” of international justice.

“There’s no enforcement mechanism so you really have to rely on states to do it for you,” he said. “And you have to rely on the stupidity of the person under an arrest warrant, who has to go to the wrong country.”

This to say nothing of the broader diplomatic implications. Legal proceedings would both be a lengthy process and likely wreck any chances of negotiation over Iran’s nuclear program.

Former NATO Supreme Allied Commander Wesley Clark, an Obama supporter, told TPM after the debate that non-military options would basically be useless at that point.

Correction: A previous version of this post misstated the UN body that tried Jean-Paul Akayesu. TPM regrets the error.