As you may know we’re in the midst of an burgeoning era of email newsletters. We have two new or upgraded ones ourselves: The Franchise (on voting rights and democracy) and The Weekender. (You can sign up for both here.) There’s also Substack, a newsletter platform which now hosts a substantial number of established journalists (and newcomers) who are striking out on their own as one-man/-woman shops with revenue from recurring subscriptions. There’s even been some controversy in the case of Substack because they have basically fronted a year of guaranteed revenue to a number of journalists with established followings. Substack thinks it will make money on those advances and does so because it wants as many proofs of concept on the platform as possible. Nothing surprising or controversial there, though some think otherwise.

A key part of the newsletter revival is the subscription model, one which I’ve discussed at great length as a key to TPM’s survival and current vitality. That is a key part of their attractiveness. The greatest financial challenge to journalism today is the dominating role occupied by platform monopolies which take from publications their longstanding role as gatekeepers and profit centers for commercial speech. Direct relationships with readers via subscriptions cuts right through that existential challenge.

But it’s not the business model of newsletters that brings me to write about them today. It’s the more intangible or elusive qualities that makes them attractive to readers. The apparently viable business model makes them attractive to independent journalists and publications. But none of it would work if there wasn’t demonstrable demand. And that demand very clearly exists.

One window into this came to me recently from an odd source. I was talking to someone from the advertising world about newsletter advertising in the very distinct Washington D.C. market. It used to be that if an advertiser was trying to announce their presence and make sure they were heard there were two or three publications where they’d place big print ads in addition to whatever more targeted, subject-matter specific placements they might do. This pattern lived on into the digital era. You do this or that targeting online but there are a handful of places you’d do a big print ad too. It’s more tangible. It is also very much not targeted.

What I was interested to hear was that email newsletters have to a significant extent taken the place of those print ads.

Now why would that be?

After all, email is one of the most ephemeral of media – stripped down, rapidly deleted in most cases. It seems like the furthest thing from print. And yet it makes a certain sense. Email is very fixed. If you don’t delete it, that email will still be sitting in your inbox a decade later. It won’t be revised or taken off line or moved to a new address. One advertisement is usually fixed to one edition of an email newsletter. And an email is fixed in other ways. It doesn’t keep evolving each time you read it. You might get sent another. But each one is set, fixed in much the way print is. They are fixed themselves and fixed in their connection to a specific advertisement.

Then there’s another aspect to newsletters which I think is central to the attraction for both readers and publishers. It’s sent. That seems like the most obvious and unremarkable thing. But it’s not. If you sign up for a daily newsletter it comes to you every day. It shows up at your virtual doorstep. The entire economy of the web relies on you the reader coming to the publisher each day, something that leaves publishers reliant on something they can’t really control.

Then finally there’s another aspect of fixity. When you arrive at a website the offerings are by nature and design almost limitless. If you show up at TPM in the morning there’s a bunch of new articles and if you follow links or search the archives there are hundreds of thousands of things you could read. Newsletters have a beginning and a fixed end. They are a report. In most cases they aim for a sort of concision or compression of information. They require choices. Here are things that matter. Others that don’t are left out.

Here I think we get to the heart of the attraction. If you really like one writer or commentator it makes sense you’ll want to read or subscribe to what they write. But you can already do that on the web. With email newsletters on every front there is fixity, limits, boundedness. It has a beginning and an end. You can lose a whole day surfing Twitter. A daily or weekly newsletter will take a finite amount of time to read and then you’re done. If you’re just looking to fritter away time you’ll need to find something else. This fixity and limitedness is recreating something that is paradoxically hard to find on the web.

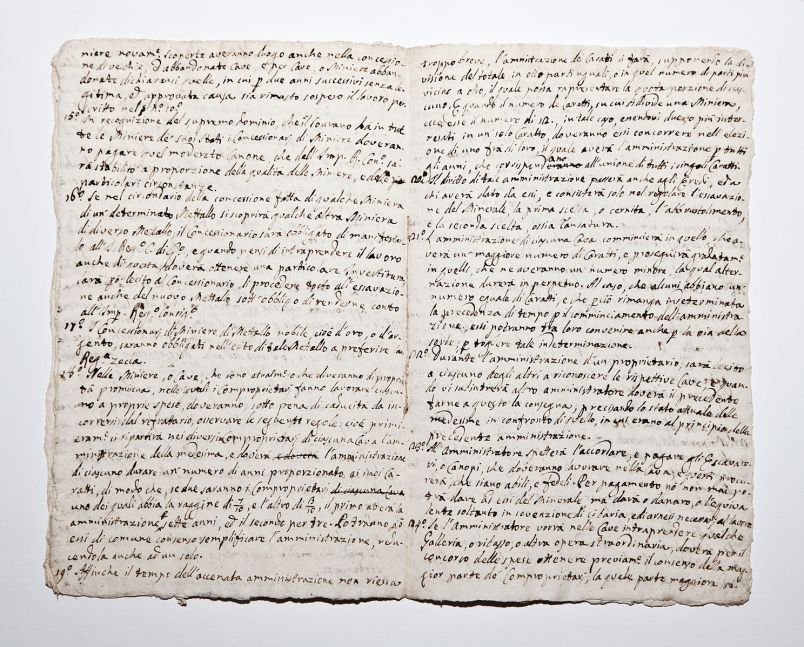

For a number of years I’ve been deeply interested in the Early Modern phenomenon of “Avvisi.” These were handwritten newsletters which have their origin and reach their apogee in late Renaissance and early modern Italy. They are the progenitors of what we know as newspapers and they existed in most of the key political and commercial capitals of the era. Given the limits of distribution and – originally – handwriting, they are necessarily to the point. They are closer to what we might think of as intelligence reports than news. (You can see some of this in the earliest newspapers and well into the early 19th century when newspapers tended to focus on advertisements and commercial information.) They tended to focus on commercial information and political and military news, all of which would be actionable news. They come from an era which we would consider information-starved. What is happening in the neighboring country or city-state? Are prices for essential goods rising or falling? Are their preparations for war? The most essential information is hard to come by. Princes and Kings tended to have ambassadors or confidantes who kept them abreast of such information. And while heads of state and government relied on the avvisi as well, what was new and notable about them is that they provided this information, for a fee, to a wider selection of people.

I’ve run fairly far afield here. But to me these are all related. We live in an information-drenched era. That is because of the fulsome technology of information, the ubiquity of surveillance which generates information and the commercial value of holding our attention. The attraction of email newsletters is that they recreate a degree of boundedness and scarcity. They make compression and concision more valuable.