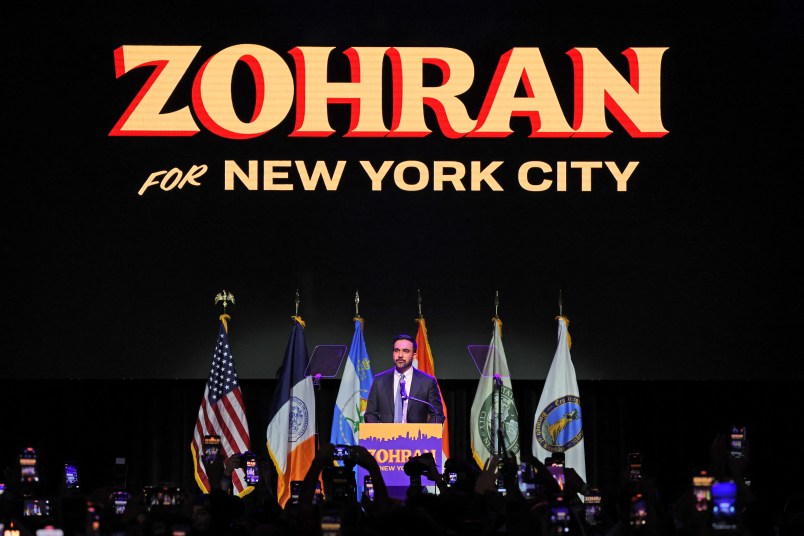

I was excited by Zohran Mamdani’s candidacy, which brought many young and minority voters, who had been turned off by the Biden-Harris years, back into the fold. I have been a democratic socialist since the late 1960s, so I also welcomed his attempt to run as one. That said, I wasn’t crazy about his victory speech.

A winning mayoral and gubernatorial victory speech is the first step in a candidate’s transition from campaigning to governing. His was angry. It lacked his smile and the whimsical humor of his videos. The speech also overpromised what he could accomplish as mayor, and it failed to acknowledge those politicians he will need at his side to accomplish anything.

There are three things that candidates use victory speeches to do: thank supporters, reconcile with opponents and their supporters, and indicate thematically, if not substantively, what lies ahead. Mamdani did effusively thank his campaign workers, his parents and wife, but he didn’t thank local Democrats like Brad Lander and Jerrold Nadler who were important to his campaign, or Kathy Hochul or Hakeem Jeffries who will be important to getting things done.

Mamdani didn’t mention Curtis Sliwa, and he was downright nasty toward Andrew Cuomo. Sure, they said harsh things about him, but that’s politics — unless you are Donald Trump. When you win, you give your opponents a nod. That’s a way of speaking to the 49 percent of New Yorkers who didn’t vote for you. I suspect, but don’t know, that Mamdani deeply resented Cuomo’s refusal to accept his defeat in the primary and his and his supporters’ attempts to insinuate that Mamdani, as a Muslim, could not give Jews or Israel a fair shake.

It is as clear as day that Mamdani will have a hell of a time achieving those of his campaign promises that require, based on the 1975 agreement during the city’s debt crisis, approval by Albany. That includes taxes on the rich and free buses and childcare. In his victory speech, Mamdani highlighted these promises — they were his refrain reminiscent of Trump’s “build the wall” in 2016 — without making clear the huge obstacles that lie ahead. Those Mamdani campaign speeches I heard, including his primary victory speech, were pitch perfect; his victory speech was not.

There was one other disquieting note to Mamdani’s performance on Tuesday. Mamdani, like Bernie Sanders, is a “democratic socialist,” and unlike Sanders, who acknowledged this identity when asked, but had said before his 2016 campaign that he preferred his policies to be described as a “progressive,” Mamdani enthusiastically embraced democratic socialism in his campaign literature and in his victory speech.

That’s fine — I’m happy to call myself a “democratic socialist” — but it depends on what it means, and Mamdani needs to be clear that it doesn’t mean the traditional Marxist conception of socialism as a new stage of history that as a result of a revolution displaces capitalism and the capitalist class. Marx and the other 19th and early 20th century socialists, including American Eugene Debs, embraced this view of socialism, which subsequent history has abundantly discredited, and which most Europeans socialists have abandoned.

Sanders himself abandoned it after the collapse of the Soviet Union and after his first unsuccessful congressional campaign in 1990 for a view that sees an American socialism building on the New Deal and on the achievements of Scandinavian socialists. It’s socialism as arising within capitalism the way capitalism itself arose within feudalism. It’s Medicare for All, worker co-determination, a wealth tax, public campaign finance — things like that.

Mamdani seemed to embrace this model during his campaign. That put him at odds with the leaders of the Democratic Socialists of America, America’s largest socialist organization, of which Mamdani is a member and upon whom he depended for campaign support. They are for the most part traditional Marxists and even Marxist-Leninists. There were two minor occurrences on Tuesday that worried me on this account.

First, Mamdani put out a video celebrating socialist congressman Vito Marcantonio. Marcantonio, who represented East Harlem in the 1930s and 1940s, was an early supporter of organized labor and of civil rights for Blacks and Puerto Ricans. But if Marcantonio wasn’t a member of the Communist Party, he was close to them — not just on their commendable support for workers’ rights, but on their subordination to Stalin and Soviet communism. For instance, Marcantonio defended the infamous Hitler-Stalin pact in 1940 and called for the United States to exempt itself from the “imperialist war” that had begun raging in Europe. He’s not someone that a “democratic socialist,” eager for the public to understand his politics, should put forth as a model.

Secondly, in his victory speech, Mamdani began by quoting Debs. Debs was a great American. He was an early champion of industrial unionism and of economic and political equality in the age of the Robber Barons. But he held an apocalyptical (Daniel Bell’s term was “eschatological”) view of the stages of capitalism and socialism that meant he opposed progressive reforms short of revolution. In Mamdani’s victory speech in the primary, he cited Nelson Mandela and Franklin Roosevelt, heroic figures who, politics aside, would also be far better known to a large television audience than Debs. If he wants Americans to accept a benign view of democratic socialism, it’s probably better to begin a speech with them.

To repeat: these are not big issues, but slightly troubling instances that could suggest that as mayor he will abandon the smile and laughter of his campaign, the liberal and centrist the Democratic officials he needs to run City Hall, and the definition of democratic socialism that many voters could understand and accept. Still, I remain hopeful and excited about his mayoralty.