The great global pandemic of the modern age is the 1918 “Spanish flu” pandemic. More than a quarter of the world’s population is estimated to have contracted the disease and tens of millions died. In recent weeks, many have pointed to it as a model for how bad COVID-19 could get. The case fatality ratio of the Spanish flu is estimated to have been between 2% and 3% of those infected. That’s roughly comparable to mortality in the epidemic in Wuhan, China.

In 1918 the world had little of what we would today consider modern medicine. There were no anti-virals, though there is yet no anti-viral approved for treating COVID-19. There were no antibiotics, which don’t directly combat a virus but can assist with secondary infections. There were no ventilators. So the world was mostly dependent on public health strategies that go back centuries or even millennia: canceling public events, closing schools, quarantining the sick.

Lack of effective communication from government or simple denial that anything was happening played a big role in exacerbating the crisis. This was at the height of War World One. Governments actively censored reporting on the spread of the global pandemic to preserve wartime morale.

Here’s the point I want to get to. What impact did this have? The failure to communicate, the speed of interventions?

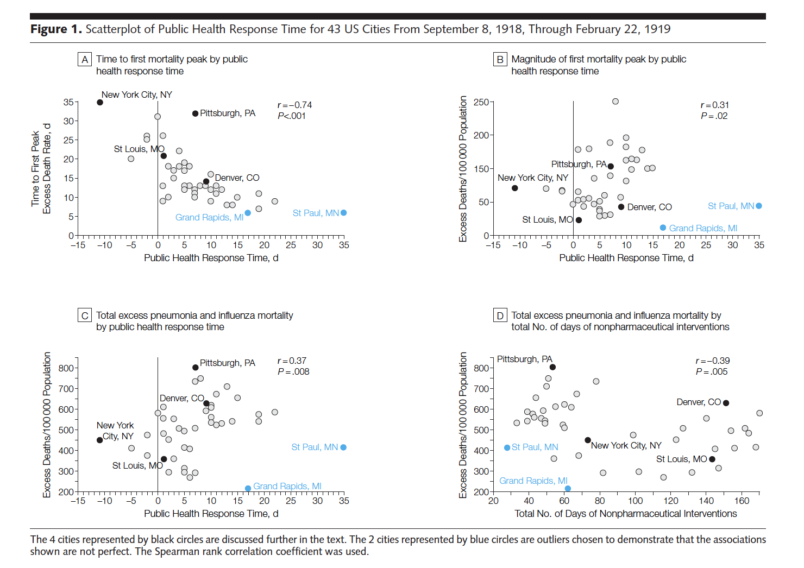

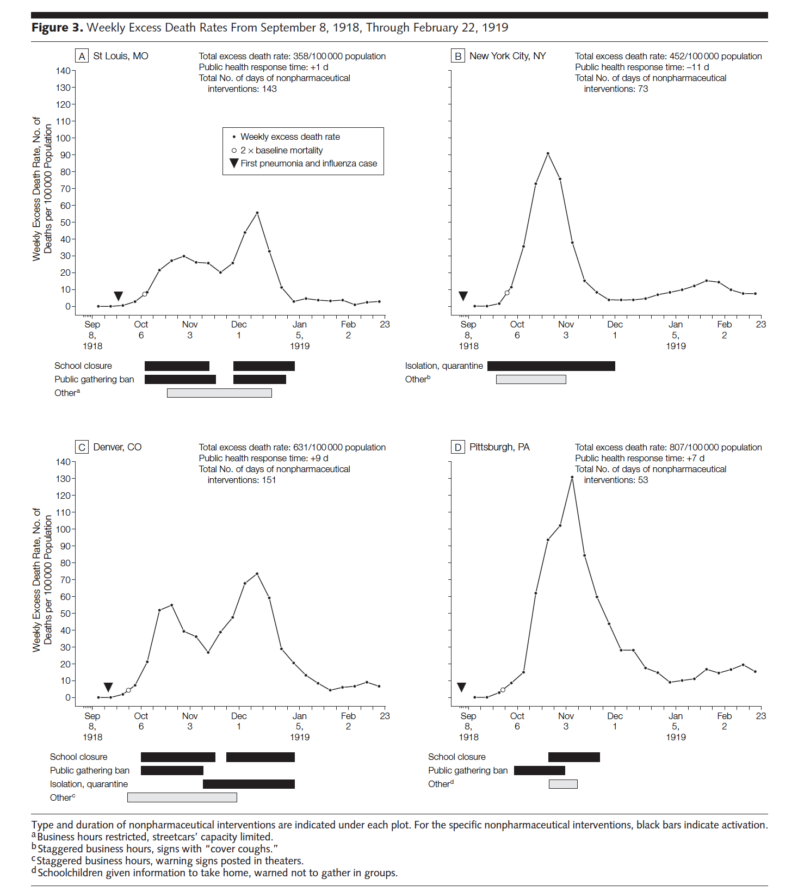

A 2007 study used modern methods to look at 43 cities in the United States that used non-pharmaceutical interventions (various kinds of social distancing) and measure when they intervened and whether this correlated with the subsequent death tolls. The gist is that the timing had a big effect on mortality in the city. Quote from the abstract: “These findings contrast with the conventional wisdom that the 1918 pandemic rapidly spread through each community killing everyone in its path. Although these urban communities had neither effective vaccines nor antivirals, cities that were able to organize and execute a suite of classic public health interventions before the pandemic swept fully through the city appeared to have an associated mitigated epidemic experience.”

The details are technical. You can make a free account at JAMANetwork and download the PDF of the full study if you want or just read the abstract. But these two sets of charts tell a lot of the story (click the image to get a full sized image if the text or numbers are too small.)

The gist is that for cities to limit the death toll they needed to act early and have a good mix of interventions. If they waited too long it basically didn’t matter what they did. The death toll would be dramatically higher.

One final point. We should not take this to mean that cities should be banning public events or closing schools now. There is a whole methodology about when it made sense to act, how long after the virus first appeared in the city, etc. That’s a question for epidemiologists and spread models. What the study makes clear though is that non-pharmaceutical public health interventions made a big difference and even relatively brief delays had big consequences measured in much higher death tolls.

[ed.note: Some readers have written in to say that the case fatality rate of 2% or 3% for the Spanish Flu can’t be right, that it must be 2% or 3% of world population. The estimates of those infected and those who died do seem to point to a significantly higher number. But this WHO publication (see page 13) says the WHO estimates the case fatality rate at 2% to 3%. So I’m sticking with that number.]