While Republicans spent the last several months threatening to filibuster the Democrats’ health care reform bill in the Senate, and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid scrambled to secure 60 votes — only to have the whole fragile arrangement blow up when Republican Scott Brown won the Massachusetts senate election last week — we kept hearing that the relatively recent rise in filibuster threats was a bipartisan phenomenon. Both parties are guilty of this when they’re in the minority, we heard.

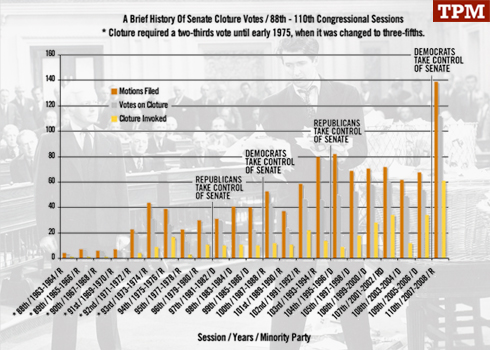

It’s true that there has been a decades-long uptick in the use of cloture filings — often to overcome filibuster threats — by whichever party is in the majority, but the best measurement of that trend shows an explosion since Republicans were consigned to minority status after the 2006 election.

Check this out:

These are the numbers on cloture over the last several decades. Often, but not always, cloture is employed by senate majority leaders in response to filibuster threats from the minority. Cloture isn’t always necessarily correlated with filibusters, but broadly speaking, the two often go hand in hand.

What’s particularly striking here is the GOP’s use of filibuster threats, and the correlated increase in Democratic cloture motions. Take, for instance, the huge spike in cloture motions filed from the Republican-led 109th Congress in 2005-2006 to the Democratic-majority 110th in 2007-2008.

“It is the most striking in history,” American Enterprise Institute resident scholar Norm Ornstein told TPM.

What happened, Ornstein says, is that during the last two years of President George W. Bush’s second term, Republicans offered “no initiatives to speak of.”

The initiatives were coming from the Democrats, and the Republicans wanted to kill ’em, or slow things down.

Republican filibuster threats, Ornstein said, were “like throwing molasses in the road.”

Of course, not all cloture motions are direct responses to explicit filibuster threats. Sometimes majority leaders use cloture filings to do preliminary headcounts and try to avoid wasted time on legislation that can’t muster enough votes.

Still, Ornstein largely attributes the stark rise in cloture motions in the 110th Congress to Republican delay and obstruction tactics.

“You’re not gonna see that sharp jump up just because you’re tracking heads,” he said.

This is a very real change in the culture of the Senate.

Sarah Binder, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a professor at George Washington University, told us that it’s not just Republicans who employ delaying and obstructionist tactics that the Democratic majority tries to overcome with cloture.

“Both Democratic and Republican minorities have been willing to exploit the rules pretty aggressively,” she said, adding that “it certainly seems that Republicans are more aggressive with it.”

Filibusters in the Senate require a 60-senator cloture vote to overcome — before the mid-1970s, cloture required a 67-senator cloture vote.

For decades, beginning with the introduction of cloture as a formal procedure more than 90 years ago, it was rare for senate majority leaders to file for cloture. As Senate historian Donald A. Ritchie told us Monday, it was just too tough to secure 67 votes — and thus very difficult to force the end of filibusters through cloture. From 1919 to 1970, cloture was never filed for more than seven times in a two-year Congress. You can see the Senate’s breakdown of the numbers here.

Things heated up about 35 years ago, when the Senate voted to change its cloture rules, lowering the filibuster-ending requirement from 67 votes to 60.

At the same time, the Senate was becoming more partisan than it had ever been, Ritchie said. Before the cloture change, strict party-line votes were relatively rare. But in the years that followed, the ideological spectrum of each party began to shrink, leading up to today, when, as Ritchie put it, “we have much more party discipline right now than we’ve ever had.”

With senators closely toeing the party line in a way that Ritchie said they rarely had before, senate majority leaders of both parties have in recent decades begun filing for cloture more and more frequently — largely as a way to gauge whether they have 60 votes for a bill before they expend time and effort on it on the Senate floor.

While Ritchie went to great pains in our discussion Monday to paint the rise of cloture as a bipartisan phenomenon, it’s not entirely clear that’s true. For instance, the two largest spikes in cloture filings in the last 20 years seem to be motivated, at least in part, by Republican obstructionism.

When Republicans were a Senate minority in 1991-1992, there were 59 cloture filings. When President Clinton took office, with Republicans remaining the minority in the Senate, that number shot up to 80 in 1993-1994.

When Democrats reclaimed the Senate majority in the 2006 midterm elections, cloture filings shot up from 68 in 2005-2006 to a record 139 in 2007-2008.

It’s important to note that there’s not a direct and complete correlation between cloture and filibusters.

“We don’t know, always, whether these jumps in cloture are because there’s more obstruction or because majority leaders need it to lend some degree of predictability to the floor,” Binder said. “In reality, it’s probably a bit of both.”

But clearly, Binder said, “the behavior of the minority is largely responsible for what the majority is doing here.”

So while it isn’t the whole picture, the rise of party-line filibuster threats has at least contributed to the increasing frequency with which majority leaders have employed cloture.

“Nothing in the Senate changed,” Ritchie said. “It’s just that the people that voters elected have changed.”