Republicans might have control of the House, the Senate and the White House, but control of all three branches of government hardly guarantees the next two years are going to harmonious for a party that has years of differences to litigate.

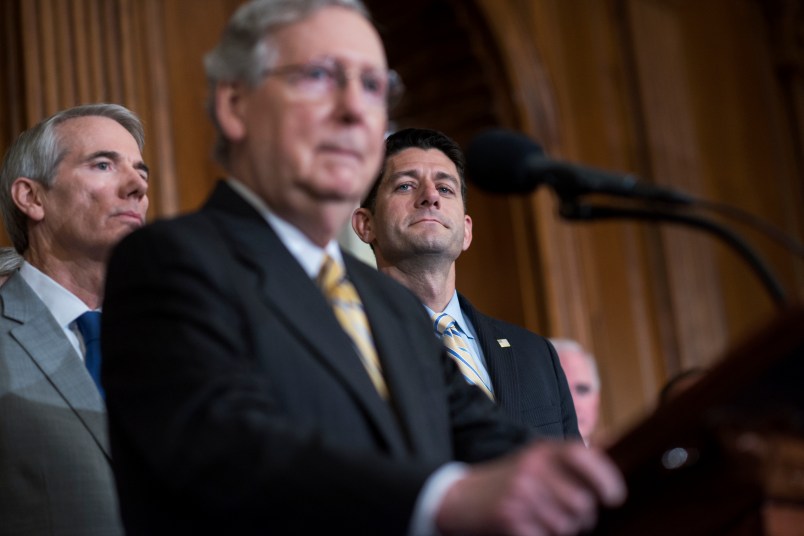

Already, the lame-duck Congress has revealed deep schisms between the vast wide-ranging agenda House Republicans hope to push through and the more limited one Senate Republicans are eyeing. For House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI), this election is his big chance to implement an agenda he’s been tinkering with for decades. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), meanwhile, warns against over-reading the party’s mandate.

The Senate, called the “cooling saucer of Democracy,” is slower in part because until recently the modern use of the filibuster created a scenario where 60 votes was required to do most anything. But by temperament and disposition – and the under the gun of having to run statewide – Republican senators have already shown themselves to more careful about tackling sweeping changes than their faster-moving colleagues in the House.

When asked last week during a press conference if the Senate was a graveyard for his ideas, Paul Ryan laughed and then responded. “I can think of a few other words.”

“We can move pretty fast. We play rugby, they play golf,” Ryan said.

The joke has long been in Washington that the enemy of Republicans in the Senate isn’t Democrats, it’s House Republicans.

“I hate the House, they’re a bunch of jerks,” Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) joked, before adding that there were some priorities like Obamacare and national defense they could compromise on.

But already Senate Republicans have tried to rein in the House’s far-reaching agenda and at times thrown their colleagues under the bus. And this comes before the new Congress is sworn in.

Experts agree that the reality is that the Senate is still likely to have the final say in many of the upcoming fights. It’s the Senate where Republicans need 60 votes to pass most any major legislative changes. That means Senate Republicans are going to need Democrats to push their agenda through.

“The House will just accept whatever the best deal the Senate can get is,” said Michael DiNiscia, an associate director at the John Brademas Center at New York University. “Trying to shove something down the Senate’s throat will never work.”

In the lame duck session, Senators have already aggressively rebuffed calls from Ryan and House Budget Committee Chairman Tom Price (R-GA) to overhaul Medicare and privatize it as they try to focus on overhauling the Affordable Care Act.

It was just days after the election that Ryan told Fox News host Bret Baier he wanted to make changes to the program. Senate Republicans quickly came out against the plan.

“I think we should leave Medicare for another day,” said Senate HELP Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander (R-TN). “Medicare has solvency problems. We need to address those, but trying to do that at the same time we deal with Obamacare falls in the category of biting off more than we can chew.”

“I think we got a pretty full agenda,” said Sen. John Thune (R-SD).

“Doing anything that is going to change Medicare will probably still scare enough Republicans in the Senate,” DiNiscia said. “There is going to be Susan Collins and two other Republicans somewhere who are just not going to go along with changes to Medicare because they are just going to be too scared.”

Medicare isn’t the only tension point, however. The House and the Senate also had a disagreement in November over how long the continuing resolution – a must-pass spending bill– should go until. House Republicans and Trump wanted the CR to run through March. They wanted the new president to make his mark on the spending agenda. Meanwhile, Senate Republicans had hoped to extend it all the way through the fiscal year to ensure their own legislative agenda wasn’t interrupted in the first months of the year by intra-party squabbles over fiscal matters.

But the fights of the lame duck may pale in comparison to what is to come.

Republicans have been campaigning on repealing and replacing Obamacare for seven years, but how to execute that promise could highlight major differences between the House and Senate. Health care experts who have spent time on Capitol Hill discussing the issues with staffers told TPM that the Senate has settled on a strategy to follow the 2015 repeal model. That keeps senators who might be nervous about repealing Obamacare on board because they already voted for the measure before and it ensures that much of the law is overhauled. Senate Republicans will take up the already-passed bill that was vetoed by Obama. It would have repealed the individual mandate, subsidies for insurers and taken away funding for the Medicaid expansion despite.

But some conservative health care advocates want more. They want to not only do away with the parts of Obamacare that affect the budget, but also want to take away the regulatory reforms, that is something that would require the Senate Republicans to override their Senate parliamentarian’s decision in order to sidestep a Democratic filibuster and pass repeal with only a simply majority.

There is also tension over whether the transition from Obamacare should take two or three years. Republicans in the Freedom Caucus want the change to happen as soon as possible to make good on their campaign promise to their more conservative constituents while senators warn that it would be better not to take away Obamacare until after the mid-term elections.

Republicans will also have to agree on FY17 and FY18 budgets next year, something House Republicans failed to do in 2016 despite the fact that Republicans had long argued that passing a budget was the cornerstone of good governance. Disagreements in the House between Freedom Caucus members and leadership halted the process. Republicans will also have to raise the debt ceiling sometime between March and June.

Adding even more confusion to the Senate and House’s power struggles will be the fact that neither Republicans in the House nor Republicans in the Senate are entirely sure of what President-elect Donald Trump’s agenda looks like. On the campaign trail, Trump shunned traditional Republican orthodoxy on trade and foreign policy. He promised not to touch Medicare and Social Security – programs that have long been considered top targets of fiscal conservatives looking to balance the budget. Trump also made an trillion dollar infrastructure bill and building a border wall a key rallying cry even though many Republicans in Congress dismissed it as untenable.

“This is unprecedented. We have never been in a situation where we have an incoming president and we have no real idea of what his legislative agenda is going to be except that it is going to be tremendous and we are going to make America great again,” said Kenneth Gold, the director of Georgetown’s Government Affairs Institute.