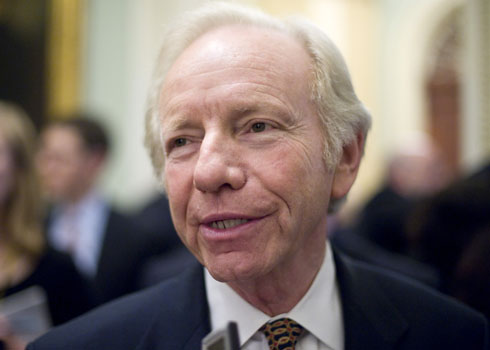

It’s no secret that Senator Joe Lieberman (I-CT) isn’t the most popular guy in the Senate, or that his rather conservative positions on national security have left many people suspicious of his motives when it comes to national security legislation. So it should have come as no surprise when CNET chief political correspondent Declan McCullagh wrote that Lieberman intended to give the President the power of an “Internet kill switch” in the event of a national emergency — and sparked an uproar.

But, surprising it was — especially to Lieberman and his staff on the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs. They argued that, in fact, the bill limited the powers already invested in the President to shut down telecommunications providers. Leslie Phillips, the communications director for the committee, said, “The very purpose of this legislation is to replace the sledgehammer of the 1934 Communications Act with a scalpel.” So, who is right?

A review of the 1934 Telecommunications Act (as amended in 1996) does indicate that the President has broad powers to simply shut off any and all regulated telecommunications if he deems it necessary for national security. Section 706 of the Act, entitled “War Emergency — Powers of the President” says:

(c) Upon proclamation by the President that there exists war or a threat of war, or a state of public peril or disaster or other national emergency, or in order to preserve the neutrality of the United States, the President, if he deems it necessary in the interest of national security or defense, may suspend or amend, for such time as he may see fit, the rules and regulations applicable to any or all stations or devices capable of emitting electromagnetic radiations within the jurisdiction of the United States as prescribed by the Commission, and may cause the closing of any station for radio communication, or any device capable of emitting electromagnetic radiations between 10 kilocycles and 100,000 megacycles, which is suitable for use as a navigational aid beyond five miles, and the removal therefrom of its apparatus and equipment, or he may authorize the use or control of any such station or device and/or its apparatus and equipment, by any department of the Government under such regulations as he may prescribe upon Communications Act of 1934 just compensation to the owners. The authority granted to the President, under this subsection, to cause the closing of any station or device and the removal therefrom of its apparatus and equipment, or to authorize the use or control of any station or device and/or its apparatus and equipment, may be exercised in the Canal Zone.

(d) Upon proclamation by the President that there exists a state or threat of war involving the United States, the President, if he deems it necessary in the interest of the national security and defense, may, during a period ending not later than six months after the termination of such state or threat of war and not later than such earlier date as the Congress by concurrent resolution may designate, (1) suspend or amend the rules and regulations applicable to any or all facilities or stations for wire communication within the jurisdiction of the United States as prescribed by the Commission, (2) cause the closing of any facility or station for wire communication and the removal therefrom of its apparatus and equipment, or (3) authorize the use or control of any such facility or station and its apparatus and equipment by any department of the Government under such regulations as he may prescribe, upon just compensation to the owners.

In other words, as Phillips told us, the President already has an Internet kill switch: he can’t shut off a website, but he can shut off any and all wireless or wired Internet access.

Lieberman’s Protecting Cyberspace as a National Asset Act of 2010 (S. 3480) is, thankfully, somewhat more complex than that. It requires that owners of critical infrastructure, a definition that dates to the PATRIOT Act, work with the newly created director of the National Center for Cybersecurity and Communications within the Department of Homeland Security, to develop a risk assessment and a plan to mitigate their risks in the case of a national cyber emergency. If an emergency is declared, that director will:

(A) immediately direct the owners and operators of covered critical infrastructure subject to the declaration under paragraph (1) to implement response plans required under section 248(b)(2)(C);

(B) develop and coordinate emergency measures or actions necessary to preserve the reliable operation, and mitigate or remediate the consequences of the potential disruption, of covered critical infrastructure;

(C) ensure that emergency measures or actions directed under this section represent the least disruptive means feasible to the operations of the covered critical infrastructure

None of those response plans expressly require that telecommunications providers develop a kill switch; in fact, the director is prohibited from requiring an critical infrastructure owner or operators from using any specific mechanism.

The owners and operators of covered critical infrastructure shall have flexibility to implement any security measure, or combination thereof, to satisfy the security performance requirements described in subparagraph (A) and the Director may not disapprove under this section any proposed security measures, or combination thereof, based on the presence or absence of any particular security measure if the proposed security measures, or combination thereof, satisfy the security performance requirements established by the Director under this section.

Phillips reiterated this point with TPMDC: “There is not a ‘kill switch.'” When asked what measures might be envisioned by the legislation, she said, “A software patch, or a way to deny traffic from a certain country. All these measures were be developed with the private sector, not imposed on it.”

In addition to the measures that allow companies to come up with their own ways to mitigate the risks to their companies (and customers) from cyber attacks, and the requirement that they use the least disruptive means possible and attempt to mitigate larger impacts, the legislation also only allows the President to impose the state of emergency for 30 days, with a potential extension of 30 days. Under current law, he is allowed to shut down any and all telecommunications infrastructure for as long as he likes.

McCullagh said, in his initial analysis, that “The legislation announced Thursday says that companies such as broadband providers, search engines, or software firms that the government selects ‘shall immediately comply with any emergency measure or action developed’ by the Department of Homeland Security.” That is slightly misleading, as owners and operators of critical infrastructure have already been identified by the Department of Homeland Security as part of the PATRIOT Act and the 2002 Homeland Security Act.

Although the full list of pieces of critical infrastructure isn’t available for download for obvious reasons, the membership of the Critical Infrastructure Partnership Advisory Council — which is designed to give those owner-operators a chance to work closely with DHS when they are developing their regulations and assessing the ways to best protect critical infrastructure — is publicly available. And, if gives a pretty comprehensive look at what, exactly, DHS considers “critical infrastructure.”

There are 17 sector committees — everything from chemical companies to nuclear facilities and shipping companies to dam operators. There is also one committee for communications infrastructure and another for information technology. The Communications Committee and Information Technology Committee have some overlap in terms of membership, but the exclusively consist of Internet infrastructure providers, telecommunications companies, some hardware companies and software companies that work in the security area. They do not include search engines, news web sites or anything of the kind — sorry, folks, the government just doesn’t consider you “critical” enough.

Phillips told TPMDC, “This language was developed with the companies who would be affected by it… The Senator [Lieberman] discussed the bill with privacy experts, civil liberties experts, companies affected by it, the Administration and the House.” She expressed a certain level of shock about the backlash, pointing us to the committee’s statements of support, which includes quotes from McAfee and Symantec executives (both members of the DHS Information Technology Committee); from the Center for Democracy and Technology — which gave a quote seemingly not in support of the bill to CNET; and from the regulation-hating U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

On the one hand, yes, it does appear that this gives the government power over marginally more companies than it has now: there are critical infrastructure owners and operators not covered by the 1934 law that would be required to come up with a plan to respond to cyber attacks that meets certain standards set by the government. On the other hand, the Emergency Broadcast System, which requires that all television and radio stations interrupt their programming with a loud buzzing noise and carry the emergency message from the government might become a thing of the past if owners and operators could find better (and less disruptive) ways to alert Americans that there is an emergency. And, regardless, the President would only have 30 days to impose the state of emergency with little oversight, and the companies would be required to be as minimally disruptive to the rest of us as possible in the emergency plans they develop.

The “kill switch,” though, won’t be coming to the underside of the President’s desk anytime soon, though. In fact, Lieberman’s people seem to be correct: their bill actually just takes it away. The bill, by the way, faces a committee mark-up on Wednesday.