Before they made the decision to deploy the so-called nuclear option, Democratic senators were well aware that their vote Thursday to end the filibuster for most nominations could be the dagger that ultimately killed what was left of the routinely used blocking tactic.

It’s the first time filibuster rules were substantially altered by a simple-majority vote, setting a bold new precedent that a future Senate majority can take advantage of. Just months ago, Republican Leader Mitch McConnell threatened to kill the filibuster for legislation — which would all but send it to the dustbin of history — if Democrats scrapped it for nominations, should he become majority leader in 2015.

“There is not a doubt in my mind that if the majority breaks the rules of the Senate to change the rules of the Senate with regard to nominations, the next majority will do it for everything,” McConnell said on June 18 during a floor speech. “I wouldn’t be able to argue, a year and a half from now if I were the majority leader, to my colleagues that we shouldn’t enact our legislative agenda with a simple 51 votes, having seen what the previous majority just did. I mean there would be no rational basis for that.”

Rich Arenberg, a professor at Brown University and former top aide to Sen. Carl Levin (D-MI) who wrote a book called Defending the Filibuster: Soul of the Senate, posited that Democrats’ move makes the death of the filibuster “inevitable.”

“In my view, the majority having now established the precedent that a majority can at any time change any rule makes it near inevitable that the filibuster will be eliminated in the Senate,” Arenberg told TPM in an email. “Over time, the majority will do what majorities do, take control. This will lead to the abandonment of the keystones of the U.S. Senate, the protection of debate and the right to offer amendments.”

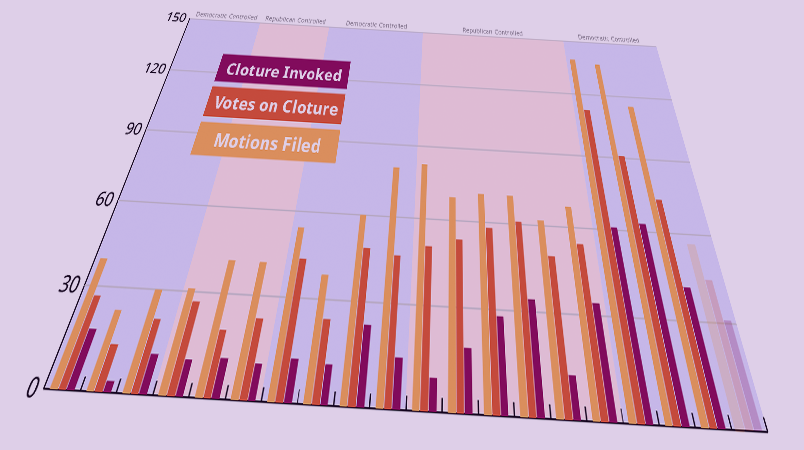

Filibuster use has grown dramatically in recent decades regardless of which party held the minority. The second chart details the growth in filibusters of executive branch nominees. In the 2000s, Democrats ramped up judicial filibusters by blocking a series of President George W. Bush’s appellate court nominees whom they labeled extreme. Republicans this year perfected the tactic with a mass blockade of three nominees put forth by President Barack Obama to the D.C. Circuit court, without taking issue with any of their qualifications.

Beyond nominees, the current Senate minority has taken stalling and obstruction to an unprecedented level, motivating Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid to finally pull the nuclear trigger. His Democratic caucus only ended the filibuster for executive nominations and most judicial nominees — not legislation or Supreme Court nominees. It is close to conventional wisdom among Democrats that McConnell would eliminate the filibuster regardless of whether this majority went nuclear, if Republicans were to take the majority in 2014 and face anything like the legislative obstruction he has incubated for seven years.

Reid shrugged off McConnell’s threat when TPM asked if it concerns him.

“Let him do it,” said the Democratic leader. “Why in the world would we care?”

The filibuster arms race in recent decades puts the Senate on a path to total dysfunction and leaves little room for a detente, lest one side unilaterally surrender. “The need for change is obvious. In the history of the Republic, there have been 168 filibusters of executive and judicial nominations,” Reid said Thursday, teeing up the rule change. “Half of them have occurred during the Obama administration — during the last four and a half years. … It’s time to change the Senate, before this institution becomes obsolete.”

While McConnell did not immediately threaten to retaliate after Democrats partially repealed the filibuster last week, his chief spokesman Don Stewart signaled that it may soon be dead.

For now. RT @toddzwillich @cbellantoni all judicial but SCOTUS. not all bills or even all noms

— Stew (@StewSays) November 21, 2013

The filibuster is not protected by the Constitution. It began as a historical accident in the early 1800s when the Senate made a rule tweak that unintentionally stripped leaders’ ability to cut off debate, according to congressional scholar Sarah Binder. As a result, any lone senator could stall and delay indefinitely, but that rarely happened for a century. In 1917, when a small minority of senators began abusing the tactic, the “cloture” threshold to end debate was reduced to two-thirds, or 67 votes. Then in 1975, in the aftermath of the Civil Rights era when the minority again escalated its use of the tactic, the Senate majority changed the rules to lower the threshold to 60 votes. At the time, the majority initially triggered the “nuclear option” but then quickly reversed the move and cut a bipartisan deal to change the rules via regular order. Now, four decades later, even though the filibuster change was partial, applying to only nominations, the precedent of altering the rules with a bare majority has been firmly enshrined.

“The Senate is a living thing,” Reid said. “And to survive, it must change.”

First chart by TPM’s Christopher O’Driscoll; second chart via Senate Democrats