The Global Islamic Media Front Technical Center is a group of mysterious programmers with links to Al Qaeda who claim to be trying to arm jihadists with digital weaponry. These high tech terrorists have released a series of plugins that purportedly encrypt instant messages to help mujahideen avoid surveillance while communicating online. However, it’s unclear if this Jihadi cryptography software is effective. In fact, experts said these programs may do would-be terrorists more harm than good by leaving behind traceable, digital breadcrumbs and even possibly exposing them to dangerous trojan horse downloads planted by law enforcement.

In February, the “Global Islamic Media Front Technical Center” released a program called “Asrar al-Dardashah,” or “Chat Secret.” It was billed as “the first Islamic program for encrypted instant messaging.”

“Allah has facilitated in the technical field its designing of the program Asrar al-Mujahideen. It is a program for encrypted text conversations, thereby recording a distinct development in Jihadi media,” declared a press release on the GIMF Technical Center website. “Asrar al-Dardashah offers the highest levels of encryption for secure communication through instant messaging.”

Asrar al-Dardashah works with an earlier piece of software released by the GIMF Technical Center in 2007, “Asrar al-Mujahideen,” or “Mujahideen Secret.” All of the GIMF Technical Center messaging programs employ so-called public-key encryption. This method involves users maintaining two sets of digital keys, a public one they exchange with those they are messaging with and a private key they do not expose to anyone else. A person sending a message will encrypt it with the intended recipient’s public key and it can only be decrypted using the corresponding private key. Public-key encryption is one of the most common forms of cryptography currently used for internet communications.

“Most cryptography applications today use public-key cryptography. Every web browser has public key cryptography, so when you do your online banking, you go through SSL and that uses pub key cryptography,” explained Phil Zimmermann president and co-founder of the encrypted communications company Silent Circle and the creator of PGP, one of the earliest and most widely used pieces of data encryption software.

Bruce Schneier, an internet security expert and author, also described the GIMF Technical Center’s use of public-key encryption as fairly standard practice.

“It’s not weird, it’s not revolutionary, it’s not interesting. The only thing here is probably the manual’s in Arabic. Other than that, it’s the same math,” Schneier said.

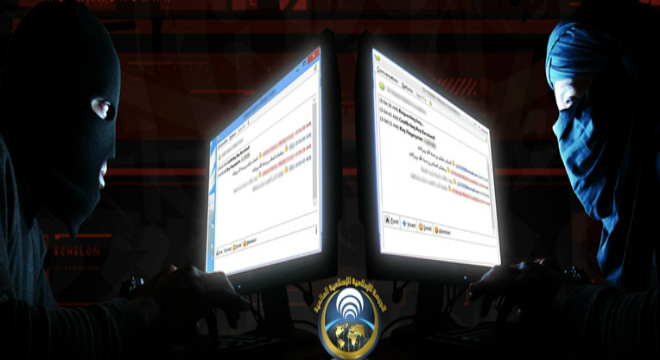

Indeed, according to the GIMF webpage where the plugin can be downloaded, Asrar al-Dardashah is based on Pidgin, an open-source messaging program used by millions of people. However, its branding was designed to appeal to the jihadist audience. GIMF’s announcement of Asrar al-Dardashah featured a lengthy statement characterizing the software as a weapon to fight the “Crusader campaign from the West” complete with splashy visuals including a dramatic image of a man in a ski mask exchanging messages with a man whose face was equally hidden by a turban and scarf (pictured above).

Both Zimmermann and Schneier agreed that, though public-key cryptography is common, it can be effective when done well. They also said it would be impossible to determine whether Asrar al-Dardashah was a quality program without conducting a thorough analysis.

“The devil is in the details,” said Zimmermann. “There’s just so many ways to do public-key cryptography and there are so many ways that you can screw this up.”

Zimmermann added that, if he did analyze Asrar al-Dardashah, given its terrorist ties, he would not want to publicly disclose whether or not he thought it was well-made.

“Whatever I found I wouldn’t tell anybody,” said Zimmermann with a laugh. “If I discovered that it wasn’t good I wouldn’t tell a soul.”

Law enforcement officials were also tight-lipped about their knowledge of the GIMF Technical Center’s work. The FBI did not respond to multiple requests for comment on this story. One former agent who worked in the FBI’s counterterrorism division told us they were “well aware of GIMF,” but did not want to comment because their knowledge of the group was “classified.”

Schneier shed some light on why law enforcement might be reluctant to discuss the GIMF Technical Center and whether or not they’ve cracked the code to Asrar al-Dardashah.

“They’re either embarrassed that they can’t break it, or they don’t want to tell you that they can,” Schneier said.

Dr. Christopher Swift, a Georgetown University professor, lawyer, and former Treasury Department official who researches terrorist organizations, suggested the effectiveness of the program may be irrelevant and that the purpose of the Global Islamic Media Front Technical Center may be “more about the propaganda of jhadi operations than it is about actual jihadi operations.” He argued the fact the software was publicly launched online shows it was designed more for potential recruits and sympathizers engaging with jihadist content on the internet than for real-world mujahideen.

“To the extent that the Islamic Media Front is, you know, putting out these capabilities at a central location and drawing attention to itself, what it’s really doing is just drawing attention to itself. It’s not necessarily the capabilities that people can use,” Swift said. “In fact, if I were a hardcore jihadi and I was sophisticated in this realm, my first thought would be that this was a false flag to get me and my buddies to buy into something that’s just going to get us rolled up by law enforcement. … A site like this its essentially a propaganda site masquerading as a resource site. … The resources are really not that helpful to a hardcore jihadi.”

It may advertise its software, but the GIMF Technical Center has no information about the group’s members is listed on its website. We did not receive a response to a message left on the contact page.

Prior to making messaging software, GIMF made a name for itself by releasing and translating jihadist videos, including some from Al Qaeda. Swift told TPM there are “probably” some members of the GIMF who are part of Al Qaeda groups, but he said it’s difficult to identify verifiable links between online activity and armed terrorist operations.

“They have been a conduit for Al Qaeda material in the past there are probably some common people between the two organizations,” said Swift of GIMF. “But, operationally … If I email something to you does that mean that I’m working for Talking Points Memo? Ideologically, they’re very close, but the operational linkages, because this is primarily an online forum there’s a lot of attenuation there. That makes it hard to tie them to operations by Al Qaeda syndicates in various places.”

Whether or not the GIMF Technical Center has strong ties to Al Qaeda, their work certainly hasn’t gone without notice in the jihadi community. In 2010, the first issue of Inspire, the mujahideen-themed magazine linked to the late Al Qaeda cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, contained an article describing Asrar al-Mujahideen. The article noted the program’s potential usefulness–and its dangers:

“Sending an important message in the old days only required a piece of paper, a writing utensil, and a trustworthy messenger that knows the location of the party you need to reach. … However, for the most part, this method has slowly evaporated and is now replaced with the Internet. Its benefit is that if there is no messenger that exists, access to the other party is only a few clicks of a mouse button away. Its harm is that the spies are actively paying attention to the Emails, especially if you are an individual that is known to be jihadi-minded,” the article said. “So how does one go about sending important messages without it being noticed by the enemy? Following is one method and that is by using an encryption software. One such software is a program created by our brothers called Asrar al-Mujahideen 2.0.”

Along with describing how to use the software, the Inspire article claimed “the enemy has created an Asrar program identical to what the brothers created … that would allow them to spy on your program.” The article advised potential users to run a check on the program’s “fingerprint” to determine if it was a “fraudulent” version. Along with warning against trojan horse versions of the program created by law enforcement, Inspire advised more old school methods of communication are more secure than encrypted online messaging.

“Don’t trust the program 100% even though it’s been proven to be effective and safe,” the article said. “Strive to use other means such as writing letters or leaving messages using special symbols in uninhabited areas.”

Swift agreed with the idea these analog means of secretive communication, known in the intelligence community as “tradecraft” are more secure for jihadists. To prove his point, he referenced the wealth of information that became known about the Tsarnaev brothers through their digital trails in the days immediately following the Boston Marathon bombing.

“The old-fashioned tradecraft is harder to track. It requires more resources in order to trace,” said Swift. “Let’s just do a comparison. How long did it take to get the Tsarnaevs’ Facebook pages, and Myspace, and all the rest versus how long did it take us to track down Osama bin Laden?”

Even if Asrar al-Dardashah is an effective encryption program, it seems the spread of the program could hurt the efforts of jihadists. Downloading false copies of software loaded with spyware isn’t the only way users seeking secrecy can potentially expose themselves to law enforcement by interacting with the GIMF Technical Center. Zimmermann said investigators often track activity on the websites of groups they are following. By visiting the GIMF homepage and other sites where its software is being promoted, jihadists may be helping law enforcement track and map their relationships — information that coulde be at least as important as what’s contained in their conversations.

“The government usually does track IPÂ addresses when they’re trying to study the behavior of an extremist group. That’s called traffic analysis,” Zimmermann said. “Traffic analysis is a very useful tool for learning about who’s talking to who. You might not be able to read the messages, but you can see who’s talking to who, and when they talk, and how long they talk. That usually yields intelligence that is as useful as knowing the content.”

Swift said, because of the potential benefits this online activity can provide to law enforcement agencies, the government has generally decided not to intervene with sites that have American roots.

“When I was at the Treasury Department, we had … an internal debate about using U.S. sanctions policy to shut down some of these websites. When I was there, I argued that it was better to have these sites open and know where they were, so then we could see what’s going on,” explained Swift. “The U.S. hasn’t made an effort to shut down jihadi websites all over the planet because those websites are a source of intelligence. They’re a source of insight into what our adversary’s thinking. Why would we ever shut them down?”