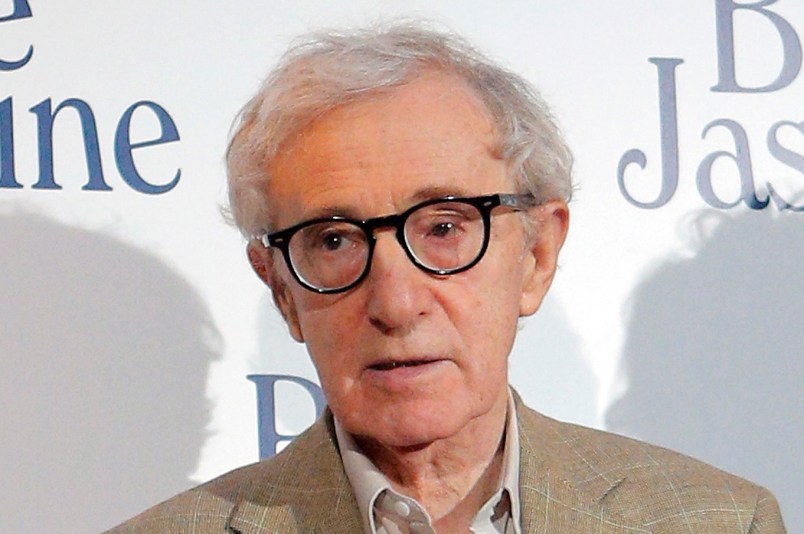

Woody Allen’s critics see his continued achievements as an affront. The chorus calling for his banishment from social influence has grown louder since last year, when Dylan Farrow wrote publicly about her sexual abuse allegations just as Allen received a lifetime achievement award at the Golden Globes. From the right, such criticism is to be expected as he has been mocking their mores and heroes on stage, page and screen for five decades. His well-intentioned critics on the left, however, are ignoring his decades of contributions to progressive thinking in the United States.

In these pages, Amanda Marcotte explored the question of why Allen has flourished professionally while Bill Cosby’s career has taken a late-in-life shellacking. Jessica Goldstein at ThinkProgress asked the same, linking to a tweet by Jeet Heer that compares Allen to Roman Polanski. If you think Allen is a child molester, either the conversation ends or you invoke the difference between “the artist and the man” (the theme Allen’s Bullets Over Broadway). Very few who think he’s guilty are willing to do the latter.

I’m disinterested in adjudicating the matter. We’ll never know whether or not he did those things. And reducing the question of whether or not Allen deserves his social prominence and accolades to “did he or didn’t he?” tosses out decades of artistic accomplishment and service to progressive ideas too rashly. For the left, Woody Allen has long been a force for good. Particularly in the 1960s and 70s, and throughout his body of work, he has advocated for peace and tolerance with singular panache.

Allen’s work typically is informed by psychology, sociology and philosophy. Broadly speaking, those all are aspects of politics, so while Allen is not an explicitly political filmmaker or writer, his work adds up to a political worldview that should appeal to secular progressives. During the Vietnam era, when he had reached prominence in American culture, he was overtly political, speaking out against the war on The Dick Cavett Show and humorously (but effectively) debating William F. Buckley in multiple forums, including Firing Line.

In Woody Allen on Woody Allen, a book of interviews with journalist Stig Björkman, Allen recalls: “I campaigned for Adlai Stevenson and George McGovern and Eugene McCarthy. All those guys who have lost.” He later campaigned for Jimmy Carter, Michael Dukakis and Bill Clinton.

During the era of his early, screwball comedies, Allen’s political ideas were overt. Bananas is a send-up of the mess that American foreign policy had made in Latin America. Love and Death, a pastiche parody of Russian literature also is a hyperparody of the Vietnam War and of the draft. When Boris (played by Allen) is conscripted to fight Napoleon, he argues that his mother would never allow it. “He’ll go and he’ll fight,” his mother announces. “And I hope that they will send him to the front lines!” A gag, sure, but pointed given how many American parents at the time supported the draft and sent their own children to fight an unnecessary war.

In a great visual gag, during a battle Boris finds himself near one of the generals on the hill where he can see the combatants from their perspective. We see two opposing herds of sheep crashing into one another.

As an autodidact in film, writing, philosophy and art, Allen is exemplar of the middlebrow intellectual urban liberal—an iconic type in the 70s and 80s. He never finished college. He taught himself by reading. He learned to write by practicing, performing stand-up comedy at The Bitter End and the Duplex in Greenwich Village and going head-to-head with the wits of Sid Caesar’s writer’s room. He learned to direct by watching movies. Allen’s journey from World War II-era working class Brooklyn to Oscar winning movies and essays in The New Yorker is what gives his films their middlebrow voice, giving them the simultaneous qualities of intellectualism and accessibility. Middlebrow isn’t as appreciated now as it was back in the “book of the month club” decades. Critics of Allen’s prominence now might not realize that his voice was much louder back then, as he lampooned Vietnam against a backdrop of Tolstoy.

Around this time, Allen lent his acting talents to a live television production of The Front, a comedy about the McCarthy era blacklist that featured formerly banned talent in numerous capacities. Though the movie received mixed reviews, it was a big deal at the time—Hollywood’s decades-late rebuke of the conservative McCarthy era and of contemporary anti-communist paranoia.

After Love and Death, we get Annie Hall and the start of the more realistic, more sophisticated relationship movies that have continued to define his style through the present day. Here we enter the world of the hyperintellectual, often neurotic, usually upper middle class or wealthy characters dealing with society and each other. Allen’s moral tone, taken in aggregate, is extremely forgiving of the improvisations that people have to make in the search for happiness. This is why Blue Jasmine is such a unique movie. Cate Blanchett plays a formerly wealthy socialite who had been married to a hedge fund Ponzi schemer. In life, Bernie Madoff’s wife Ruth was gleefully attacked in the city tabloids for years after Madoff’s fund unraveled. In Blue Jasmine, the former wife is presented as a sympathetic fish out of water, trying to rebuild her life.

Most Hollywood movies take a morally conservative view of good and evil. Audiences are meant to delight in the punishment of villainy and the standards of morality expressed typically lack nuance. Such black-and-white standards rarely show up in Allen’s oeuvre. In Crimes and Misdemeanors (and several other later Allen films)murder goes unpunished. In Manhattan, a 40-something man dates a brilliant 18-year-old high school student and the only punishment he receives is the heartbreak of her leaving for college abroad. In Deconstructing Harry, a troubled writer comes to terms with the people he perceives as his life’s antagonists by ultimately forgiving them for everything even as they continue to despise him.

The worldview here is deeply progressive. This is art that takes no glee in punishing sin. It recognizes that life is hard and that compassion for others, as well as giving people the benefit of the doubt, are life’s paramount virtues, followed closely by pleasure seeking.

Yes, this has manifested in the artist’s life. He married the adopted daughter of his ex-lover, Mia Farrow. That is not exactly standard operating procedure, to say the least. To some, this is deeply disturbing, though I have a hard time understanding why anybody outside of their orbit should care. Allen and Soon-Yi Previn have been together since 1992 and married since 1997. By most accounts, they seem to be a normal, happy couple. As in one of his movies, what outsiders might consider wicked turns out to be something that works. Life is messy.

Allen’s collaborations with Diane Keaton, Mia Farrow, Dianne Wiest, Helena Bonham Carter, Mira Sorvino, Scarlett Johansson and Emma Stone (the list is not endless, but it’s long) have resulted in major awards for the actors, even in cases where the films were not widely celebrated and Allen has earned a reputation for writing uncommonly well-rounded and interesting female roles. Like anything, these characters are not for everybody, but year after year we have seen important woman actors take lower-than-their-typical pay (Allen’s movies are relatively low budget) to work with him. The degree of loyalty perplexes Allen’s detractors but it persists. To me, these endorsements speak better of Allen’s character than his critics are willing to allow.

As a progressive, I’ll take my cue from a progressive artist, look at Allen’s life and decide to not judge. The country is better off with him as a cultural force and his ideas about politics and how we should treat each other are ones that his critics on the left would do well to embrace and to extend to the auteur.I’m looking forward to a Woody Allen movie a year for as long as he can, and this Amazon series, as well.

Michael Maiello is a playwright, author and essayist. He has written

for Esquire, McSweeney’s, The Daily Beast, Reuters, Forbes and

theNewerYork.

Why is Woody Allen’s life as a progressive is worth saving and Bill Cosby’s is not? Cosby did many things that progressives cheered at the time. I remember a couple of days after 300 Hollywood celebrites signed a full page ad in the LA Times declaring their support for beleguered Gov. Ronald Reagan that Bill Cosby took out two facing full pages ads declaring that he didn’t.

But then again, Allen does deserve reassessment.

TL;DR - The white guy should get the benefit of the doubt while the black dude gets lynched.

Well, if you believe the worst about Allen (not saying I do) he appears to have offended exactly once (taking up with Soon Yi is unusual, but not criminal). That’s the worst that accusers–who hate him for other reasons–are saying about him (Allen does not appear to have disinterested accusers).

Cosby has been accused of serial offenses, by many different women who have no or little connection to each other. Many of the accusers have no other reason to attack Cosby. To many, it seems pretty unambiguous, and disturbingly central to Cosby’s character.

Cosby also isn’t a progressive icon in the way Allen is. Cosby’s contribution was putting an acceptable black face into mainstream white culture. But he did it, in part, by denying and attacking some aspects of black culture. He seldom if ever challenged white culture to examine its own hypocrisy and flaws, and instead appeared as a safe, non-challenging black person.

Which had importance. Simply creating the idea of middle-class black families was something of a revolution, at the time.

But that idea goes no further than its immediate effect on culture. Cosby’s contribution doesn’t lead to a lot of deeper understanding of America’s take, progress and reaction to race relations. It just portrays a nice black family that a lot of white people felt comfortable with.

Thanks for a well-written and well-reasoned article. I think you have made many valid points about the value of Allen’s contributions over the years. I take no position regarding the allegations made against him and think they are really irrelevant to the value of his art.

I don’t know what to make of the allegations against Allen, and don’t intend this to be a comment upon them one way or another.

I think that Allen’s heart is in the right place, but that as a practical matter it’s very hard to get progressive politics right if you don’t hang out with people who have normal jobs. I mean, people who live in mansions and have many millions of dollars, and only associate with extremely accomplished and successful people aren’t going to have an easy time getting the priorities right, even when they’re good, compassionate people.