When it comes to education, family engagement is a good thing. Or, rather, it’s a Good Thing. It’s one of those hallowed variables rumored to be potent enough to make or break the success of a student, class, or school entirely on its own. For instance, when analysis shows that charter schools outperform district schools serving similar students, many charter skeptics respond that this simply reflects the “fact” that charters have more engaged parents.

Furthermore, family engagement fits well with our notion of schools as democratic institutions, as places where families come together to share in the common project of educating the next generation. Obviously public institutions, with a public mission, should be places where the public remains actively engaged. This is particularly important when schools aren’t working — shouldn’t parents have a way to pressure schools to make changes when they feel as though their children aren’t being served?

And yet, as good as all this sounds, when you run the numbers, family engagement doesn’t appear to matter much for students’ academic success. Or, rather, engagement for the sake of engagement doesn’t make much of a difference. Believe it or not, parents staffing the refreshment stand at football games don’t make a difference for their school’s effectiveness. There are lots of ways for families to get involved in schools, and they’re not all helpful.

Is there a way to encourage more and better family engagement by making parents a powerful force? In 2010, California passed a law giving parents the opportunity to organize and assert some control over the future of persistently low-performing schools. If they collect signatures from over 50 percent of parents with children at the school, they can force the district to take remedial action to change the school — by replacing the staff, bringing in a charter operator, or closing it entirely (among other options).

The politics of the “Parent Trigger”law are fraught. Unions have long opposed the idea as one that demonizes school staff and splits school communities into factions. When parents successfully used the law to force changes at one school, prominent education reform opponent Diane Ravitch consigned the community organizers involved to “a special place in Hell.” Meanwhile, at Desert Trails Elementary, the law was used to replace the district school with a charter school. Still, the vote was close and sparked acrimony in the community and vandalism in the building.

There’s no question that wholesale school overhaul is a dramatic move. It’s pretty far from a PTA bake sale. But aren’t dramatic changes appropriate when it comes to consistently ineffective schools? Should we tinker around the edges while students continue to attend so-called “failure factories”?

Recently, a group of parents at South Los Angeles’ West Athens Elementary School showed another way to use the law. Families concerned about persistent bullying and what they saw as an unsafe school environment recently formed a parents union — the “Aguilas de West Athens” (Eagles of West Athens). Lerina Cordero, a parent at West Athens, told LA School Report that parents had been pushing for changes for years, but “it wasn’t until we said we were going to use the Parent Trigger law, that the principal finally sat down to meet with us.”

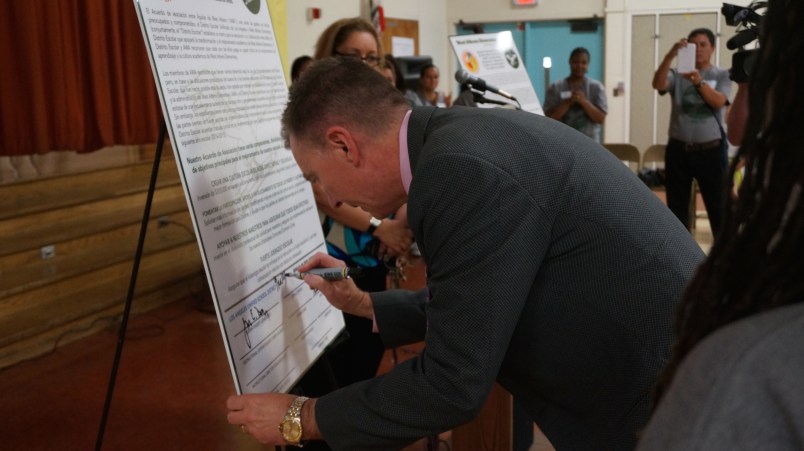

Once the school realized that the parents were considering that option, the doors opened. The ensuing discussions culminated in a public ceremony last Friday: LA Unified School District Superintendent John Deasy visited West Athens Elementary to sign an agreement committing the school and district to a series of actions aimed at improving Common Core implementation, school culture, and school safety.

Given the tempestuous politics of past uses of the parent trigger law, I asked United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) president Warren Fletcher for his perspective. He argued that the situation in West Athens wasn’t about the parent trigger, since it wasn’t actually “pulled.” To Fletcher, this seemed like a straightforward case of parents organizing to improve a school — something which he believes could work better without the current law. He also expressed concern that the final agreement was too general to be meaningful. It commits the district to add a school psychologist, but also to “creating an environment that motivates and fosters learning.” After reading that line, Fletcher said, “The last thing UTLA would want to do is discourage parents from being involved … but most of the stuff in there is very general. I don’t know if it requires an agreement.”

Perhaps this is why members of the parents union see the agreement as the beginning of their work, not the end. West Athens parent Angelina Jauregui told me, “I’d like [the school] to change its practices to improve … First of all, it’s about security. But I want my children to go far—to college and beyond. That means that we have to stay involved in the school, volunteer, and support the teachers.” Jauregui also noted that she saw the law as a way of holding the district accountable to the agreement.

Sadly, most families stuck sending their children to failing California schools come from the bottom of the American socio-economic ladder. Too often, these families face enormous economic, social, and health challenges. For some, school involvement is a heavier lift than it is for wealthy families in the suburbs. This isn’t because they don’t care about their children or are somehow prisoners of a “tailspin of culture” — it’s because they’re often overworked, underpaid, and already stretched to the breaking point. Worse still, parents who are interested in getting involved at their schools often find — as Cordero did — that school leaders aren’t open to their feedback, let alone big changes.

When I asked Gabe Rose, one of the community organizers working with the parents, if he agreed with Fletcher that the parents could have been successful without the parent trigger, he laughed. He then pointed out that the agreement specifically identifies the parents’ rights under California’s parent trigger law. “I mean, you can get tied up in the metaphysics of whether the parents actually ‘used’ the trigger, I guess,” he said. “But it’s mentioned right there on page two.”

Perhaps the parents in West Athens are illustrating the way the parent trigger should really work: it gives parents more leverage than moral outrage when it comes to improving their children’s schools, but it also gives administrators, teachers, and districts a chance to take their concerns seriously. If so, that would be a Very Good Thing.

Conor P. Williams, PhD is a Senior Researcher in New America’s Early Education Initiative. Follow him on Twitter: @conorpwilliams.

—

Photo of agreement signing ceremony in West Athens, courtesy Parent Revolution.

It’s a little sad when that’s what it takes to make administrators pay attention.

Sad, but not surprising. When people are virtually impossible to fire, they act like it.

Once again, all responsibility for a child’s academic success is placed on the school - whether administrators or teachers. Once again, those who don’t actually teach complain when children don’t succeed.

Here’s a few questions you might want to ask: 1. How many children are English Language Learners? 2. How many children have parents who were not successful in school? 3. How many children have parents who are not helping their child succeed in school. 4. How many children have parents who don’t know how to help their child succeed in school? 5. How many children have parents who think erroneously, as so many others do, that their child’s academic success is solely the responsibility of the schools? 6. How many children have inadequate nutrition, health care, and/or dental care? 7. How many children are being abused, terrorized, or are afraid in their homes or communities? 8. How many children have already fallen into the cycle of failure because of social promotion?

Are you aware that children who don’t master the curriculum in 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc., grades are moved along to the next grade and NOT given remedial instruction? Are you aware that children in some California school districts receive grammar education only in the 3rd grade, and never again? Are you aware that science and social studies education in elementary and middle schools is practically non-existent because of the pressures of standardized testing, especially the CAHSEE being concentrated on English Literature and Math?

Teachers can only do so much. Without parents letting their children know that they are expected to work hard to succeed, the child learns early that they can sit back and relax and still move along to the next grade. Until they get to high school, of course, and then they don’t believe it when we tell them they must get passing grades in order to graduate.

There’s a lot wrong with public education, mainly caused by all the attempts to “reform” it, compounded by the idea of standardized testing to ‘hold teachers accountable’. Who is holding the student accountable?

Laying the blame on anything but the child and the parents for the child’s failure to succeed is counter-productive and will only erode the schools even more.

Oh, and BTW, stop with the “impossible to fire” garbage. Teachers must also meet standards, and can be removed from their jobs just as easily as anyone else. Stop listening to those who want to privatize education.

I have two kids, one already graduated from Public Schools in Southern California, and one in the fifth grade.

My youngest made second high honors for all three quarters, and looks likely to finish the 4th quarter with all A’s and B’s as well. And yes, there are many nights where me and his mother are up until 9 or 10 o’clock at night helping with his homework. However, here is a key difference you fail to mention.in your screed.

My son doesn’t get paid or get a pension for going to school. Me and my wife don’t get paid for all the hours we put in. THE TEACHER GETS PAID! BECAUSE THAT IS SUPPOSED TO BE THEIR JOB!

Second, your stuff about passing kids along is nonsense. After the first grade, they can, and do retain kids who don’t master the curriculum. The school district my kids go to threatened to retain my oldest son when he was in second grade if he did not pass the standardized State tests.

Your last comment, is just too much to stomach.

If Teachers are as easy to remove from their jobs as anybody else, then why did the LAUSD pay Mark Brendt $40,000 to resign?

This is the same teacher who feed his semen to blind folded students as part of the “tasting game”.

Here is your answer. Because it is easier to convict a child predator in a court of law, than to fire them for lewd acts in the LAUSD.

.

Why pay a criminal to resign rather than go through the due process required to fire them? Perhaps because convening the right people, including the lawyer for the school, would have cost more than $40K, and they wanted to get the process over with as quickly as possible?