If you ever visit the New Jersey State House in Trenton, something to keep in mind is that there is plenty of free parking. And, of course, this being New Jersey, you’ll never be far from a highway if you need to make a quick getaway.

I learned this in 2002 when I made the rookie mistake of paying for metered parking on West State Street. It seemed like a great spot. New Jersey’s capital isn’t situated on a bucolic hill evocative of the country’s idealized pastoral origins; it’s on a street, and you can’t miss it. The architect who designed the facade was doing his best to keep up with the City Beauty movement of the early 1900s, so it looks nothing like the 19th century Federal and Greek Revival row houses and brownstones just down the block that are today used as lobbyists’ offices.

With the exception of school tours, the building is ordinarily very quiet. Despite the fact that the 120 members of the state assembly and senate are paid $49,000 per year, serving in New Jersey’s legislature is considered to be a part-time gig. Most members have other jobs; many are lawyers and until recently many actually held another elected office. This meant you could be a mayor and state senator and hold down yet another job, all at the same time – something you don’t find in many non-feudal modern states. (The state outlawed the practice of plural office-holding a few years ago. And the only plural officeholders who now remain were grandfathered in as part of the rule change.) Because of this, unless one of the legislative houses is in session, the capital can feel deserted even on a business day; everyone has somewhere better to be.

On this particular Sunday, however, the building hummed. It was early July and Jim McGreevey, the newly-elected Democratic governor, still hadn’t gotten a budget fully approved by the state legislature. Inheriting a $5 billion deficit from Republican Christie Todd Whitman’s administration, McGreevey had come out with tax proposals that fell flat among fellow Democrats. With the fiscal year over, the governor used his powers to call a special session of the legislature on the Sunday before July 4 to force the state senate to approve a funding package. It was hot. It was before a holiday. Everyone wanted to be somewhere else. The assumption was that people would vote for something just so they could go back home.

At the time I was working as a political reporter for PoliticsNJ.com, for an anonymous editor known then as Wally Edge and who we today know as David Wildstein, the former Port Authority director of interstate capital projects who orchestrated the lane closures in the George Washington Bridge. I was at the shore in Cape May County that weekend, driving a car with a failing air conditioner. I drove up to Trenton in khakis and a t-shirt with the windows down and a water bottle packed with ice. I parked on West State, fed the meter, and ducked into the capital through a side door to get properly dressed. Unlike the state assembly, the doorkeepers in the New Jersey senate enforce a dress code on the floor of the chamber. For me, that meant no jacket, no tie, no story.

But it turned out there was an exception being made that day.

George Norcross III, an insurance executive and former chairman of the Camden County Democratic Party in South Jersey, was seen everywhere in the state house. Norcross had gotten rich by selling his insurance business to Commerce Bank, which was then winning accounts with municipalities, state authorities, county governments, and other public entities across the state. He was on the board of directors of Cooper Hospital in Camden. He was a key fundraiser for McGreevey. He recently bought a majority stake in the Philadelphia Inquirer. Norcross was and remains a hand visible and invisible in New Jersey politics, and one cannot understand the state without appreciating the alliances he forged in North Jersey that allowed him to hand-pick the current assembly speaker and senate president while also backing Chris Christie’s 2013 re-election campaign. Those alliances are not grounded in goodwill, but are the product of hard-fought back room politics and are sustained by the lifeblood of all New Jersey political alliances: money.

On this day in July, Norcross knew he had leverage. McGreevey needed votes, and Norcross could deprive him of those votes if the legislators he controlled withheld support for the governor’s plans. His plan was to get McGreevey to support the construction of a $65 million sports arena in Pennsauken, a Camden County suburb. South Jersey legislators like to claim that all the good projects go to North Jersey. They tend to be less enthusiastic, however, when discussing why George Norcross supports the projects he does. In 2002, nobody wanted to mention that Norcross owned a $500,000 stake in the ice hockey team he planned to house at the publicly-funded arena in Pennsauken.

Yet there he was that day, seemingly everywhere. In the assembly chambers. On the senate floor. And breezing in and out of the governor’s office, through the double glass doors, past the state trooper sitting at the front desk, past the receptionists, through the outer office where press conferences are held and where deputies man their desks, and into the inner sanctum of the governor’s private office. Just as if he was member of the staff or a constitutional officer elected by the voters. All so that he could lobby for public funding for an arena that the state didn’t need and couldn’t afford to house an ice hockey team he co-owned.

In Trenton, as in all state capitals, there are rules that lobbyists have to observe. They must wear name tags and register with a state office to disclose who is paying their salaries and on which occasions they officially lobby on behalf of a particular client or for or against a specific piece of legislation. These strictures are meant to contain the influence of lobbyists and force at least some of their activities into the light of day. But they are a feel-good exercise. They fail – utterly and completely – to capture, in any meaningful way, the scope and scale of how influence is exercised and deployed in the construction of public policy in America in the 21st century. Everyone seems to know this in Trenton, as well as in Washington. Disclosure is so yesterday, a relic of the a time not so long ago when it seemed possible to pry public and private interests apart and construct a more perfect union from more noble intentions.

What was interesting to me – and perhaps only to me – that day in 2002 was that George Norcross didn’t have to follow even those insufficient rules. And nobody seemed to expect him to. Whereas I’d put on a jacket and tie to go speak to state senators, Norcross brushed through the chamber’s doors in a golf shirt and summer slacks, headed straight to the senate president’s office behind the rostrum. Then he’d come back out, and rush back to McGreevey’s office. At one point, two or three of us reporters caught him in the hallway outside the governor’s office as he was headed back to the senate. Without missing a beat, Norcross said he’d just been working in his “Trenton row house” – a reference to the nearby buildings lobbyists used because of their proximity to the state house. In this case, Norcross was calling the governor’s office his Trenton row house as he inserted himself into the state’s budget drama to further enrich himself at public expense.

It went on like that. All day. Finally in the evening, as votes were being held up over another arena, this time in Newark, Norcross got into a shouting match with the president of the state senate in the president’s office. It was loud. His people denied it, but I was sitting ten feet away with future governor Richard Codey at the time. We both heard it. It happened.

Statistically New Jersey does not suffer from an unusual amount of corruption. Sure, we put big numbers on the board, but we’re nothing like Louisiana or Illinois or parts of the old Confederacy. We garner an unusual amount of media attention when a scandal comes to light since we’re wedged between the media markets in Philadelphia and New York; nobody wants to pay attention to New Jersey until there’s a freak show to cover, and so those are the stories that the rest of the country hears.

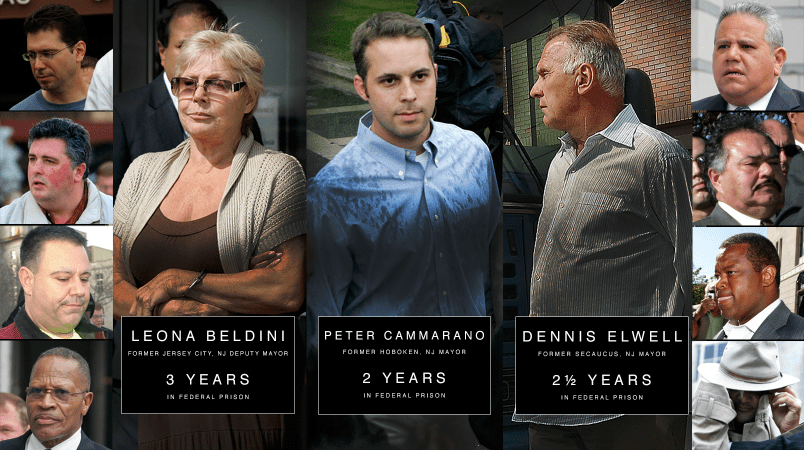

Moreover, those are the stories we remember. In the last 12 years I’ve seen politicians at all levels of government in New Jersey face arrests, trials, and jail. Off the top of my head so many names come to mind that it is hard to remember who’s still doing time and who’s out and who ended up taking a plea bargain.

But these details are distractions. And in many ways those very prosecutions are exceptions. To grasp how endemically corrupt New Jersey politics is you have to understand that shakedowns and private enrichment are so completely mundane that many people in state politics read grand jury indictments to study up on the latest innovations in prosecutorial technology and figure out how someone made the mistake of getting caught.

When I think about this story of George Norcross twelve years later, I come back to it as someone who’s spent a good amount of time thinking about public and private interests and how and why mixed economy institutions were introduced into the nation’s political economy. What’s striking is how cultural and systemic the problems of corruption in New Jersey politics now seem to me.

In retrospect, the high-profile prosecutions of political actors that rooted out ‘bad apples’ in New Jersey look no more effective than the scrutiny directed toward the financial sector in the wake of the 2008 crisis. Bad actors were called out, but those with a stake in the status quo demanded that nothing more be done. The underlying problems and misaligned incentives that caused the financial crisis remain intact. Similarly, Chris Christie succeeded in putting some crooked politicians away during his time as U.S. Attorney for New Jersey, but as governor he (and/or his staff) seems to have succumbed to the same temptation to use his office to extract favors or exact revenge for all the wrong reasons. One of the ways Christie won and maintains power is through his alliance with George Norcross. Christie’s election not only confirmed Norcross’s influence in the state; it intensified it. The onetime prosecutor rode to power promising to be revolutionary, but his administration is now unraveling because of their own counterrevolution.

Now, I don’t mean to lay all of the state’s ethical problems at the feet of George Norcross III. He’s just playing the game as well as anyone can. The problem is that this game is rigged.

The New Jersey constitution makes the office of governor particularly powerful compared to other states; in New Jersey, all state judges and even the attorney general are appointed positions. The office was designed to free its occupant from dependence on county-based political party organizations and their bosses.

In theory, it was a great idea. The only problem is that the county bosses never went away, and once campaigns became expensive (remember those New York and Philadelphia media markets), governors became dependent once again on county parties for fundraising and election day get-out-the-vote operations. By the time they actually take office, statewide elected officials have had to make so many deals with county party chairmen that they’ve already surrendered whatever independence they might have gained from their election. Jim McGreevey simply wasn’t powerful enough to stand up to George Norcross in July 2002. Nobody on his staff could gently suggest to the Camden County Democratic Party chairman that it was unseemly to refer to the governor’s office as his lobbying office. The doorkeepers in the state senate chambers, who are themselves political retainers, dared not risk enforcing the rules on coats and ties. After all, what does a dress code mean to someone who thinks nothing of dressing down a legislative leader within earshot of his peers?

If we think we can constrain this behavior with new laws, or more disclosure, or anything that can go into a box on a quarterly form filed with a state office of ethics, we are mistaken. For although these problems are partly institutional – that is, grounded in inadequately drafted laws and flawed designs of governance – they’re also cultural. Some of the most surprising – and, to be honest, depressing – conversations I’ve had in the last week have related to the accusations Hoboken mayor Dawn Zimmer publicly leveled against the Christie administration last Saturday. Zimmer says that top administration officials linked Hurricane Sandy relief funding to her town’s approval of a redevelopment project that will primarily benefit a client of Christie ally and Port Authority chairman David Samson.

To some, the remarkable thing about this story is how naive they think Zimmer seems. “She doesn’t get it – this is Jersey politics,” one person told me.

Along the same lines, one elected official told me privately that the reason he liked the connection Steve Kornacki and I drew between the George Washington Bridge lane closures and the Area 5 redevelopment project in Fort Lee was that it spoke to a truth about the state’s politics. “You guys see that it’s all about land,” he said, “and you get what politics is really about in this state: wringing as much fucking money out of the system as you possibly can before you get caught.”

We’ve spent centuries thinking about politics as a competition for power. We assume that a thirst for power is what animates almost all political acts. This assumption is so embedded in the vocabulary of government and the rhetoric of electioneering that we have been blinded to the possibility that another motive is exercising equal pull: greed. People can get rich, very rich, by dipping their toe in New Jersey politics.

Until we understand how the linkage between patronage, development, and infrastructure makes that possible, the political culture of the state simply won’t be equipped to make any real reforms.

Brian Murphy (@burrite) is a former political reporter in New Jersey and now an assistant professor of history at Baruch College, where he studies political economy and the politics of banking and infrastructure in the early American republic. He worked for David Wildstein in 2002 as the managing editor of PoliticsNJ.com and is also a friend of Bill Baroni. Both men are intimately involved in the scandal. He has not spoken with either about the scandal. He has never met Wildstein in person, and has not seen Baroni since 2009.

The problem with New Jersey is

George E. Norcross lll and every Governor and AG

That has gone along with him. Norcross is a danger to our national security and safety in America.

His brother in Congress is a danger to our

Military and national defense.

They have conspired with Facebook; twitter; Amazon; Advance Local NJ.com; Gannett Courier Post and a host of companies that have interfered in illegally invading our emails, cell phones, computers and security. They are illegally wiretapping our conversations

Norcross serves on a cyber security

Company board named Delta Risk LLC.

Which is owned and operated by his attorney and friend Michael Chertoff former head of homeland security under bush. There is so much illegal activity going on in that cyber company and with NJIT in NJ

Norcross family, Chertoff, Hayden, Christie, Sweeney, Ayscue, Roger Stone, Manafort, Trump and all his little buddies hatched a cyber organized underbelly to track the world and

Get information on people’s past then create manufactured stories and use them against

them.

It is deeply criminal what they are doing to people

It is so protected by the government, mob and

People in law enforcement; military; lawyers; judges courts and Social Media

Norcross is demonic an anti Christ who has invested in weapons: energy, oil and nuclear control. He’s a drug lord; sex trafficker; world bank owner and director of fake news and online harassment

He MUST be stopped but he and his brother play both sides. His daughter is no better. She too has been the orchestrator of fake news and sex scandals

Steve Ayscue is working with Roger Stone In creating highly negative story telling. They were behind the hundreds of fake Facebook sites that Zuckenberg allowed them to set up

This is a serious cyber crime organization.

Norcross and his entire network must be stopped but he has too many bad people protecting him and profiting off the money

The Jersey devils

Norcross

Sweeney

Ayscue

Christie

Trump

Stone

Manafort

Mayer

Beach