This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

As the Texas blackouts stretch into their third day, misleading narratives about what went wrong have spread far and wide. One particularly pernicious one you may have heard is that wind and solar are to blame for the outages.

But what so many of these assertions lack is a fundamental understanding of Texas’ electric power supply, and its mutual vulnerabilities with the state’s gas systems. We’re facing an energy systems crisis here in Texas, not just an electricity crisis.

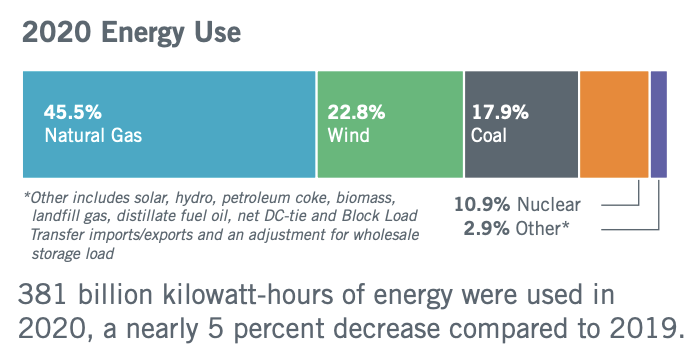

To understand why, we can begin by looking at how the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) — which operates our electrical grid — generated power on average last year. Nearly half of it came from natural gas. Wind surpassed coal for the first time. And four nuclear units and a bit of solar and hydropower supplied the rest.

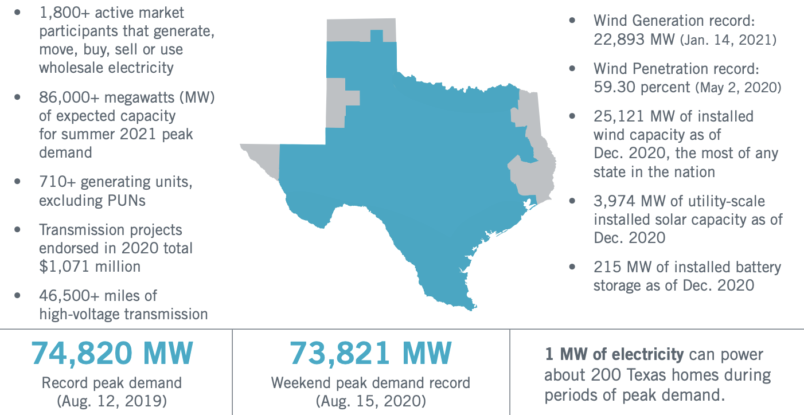

That supply provides power for most but not all of the state. The grid is contained within Texas, with very little transmission linking to the rest of the country or Mexico. So what happens in Texas stays in Texas.

The grid can operate just fine with very high levels of wind — over 50 percent at times. With solar power also variable and nuclear power usually fixed, coal and gas plants flex their output to satisfy remaining demand that itself varies with time.

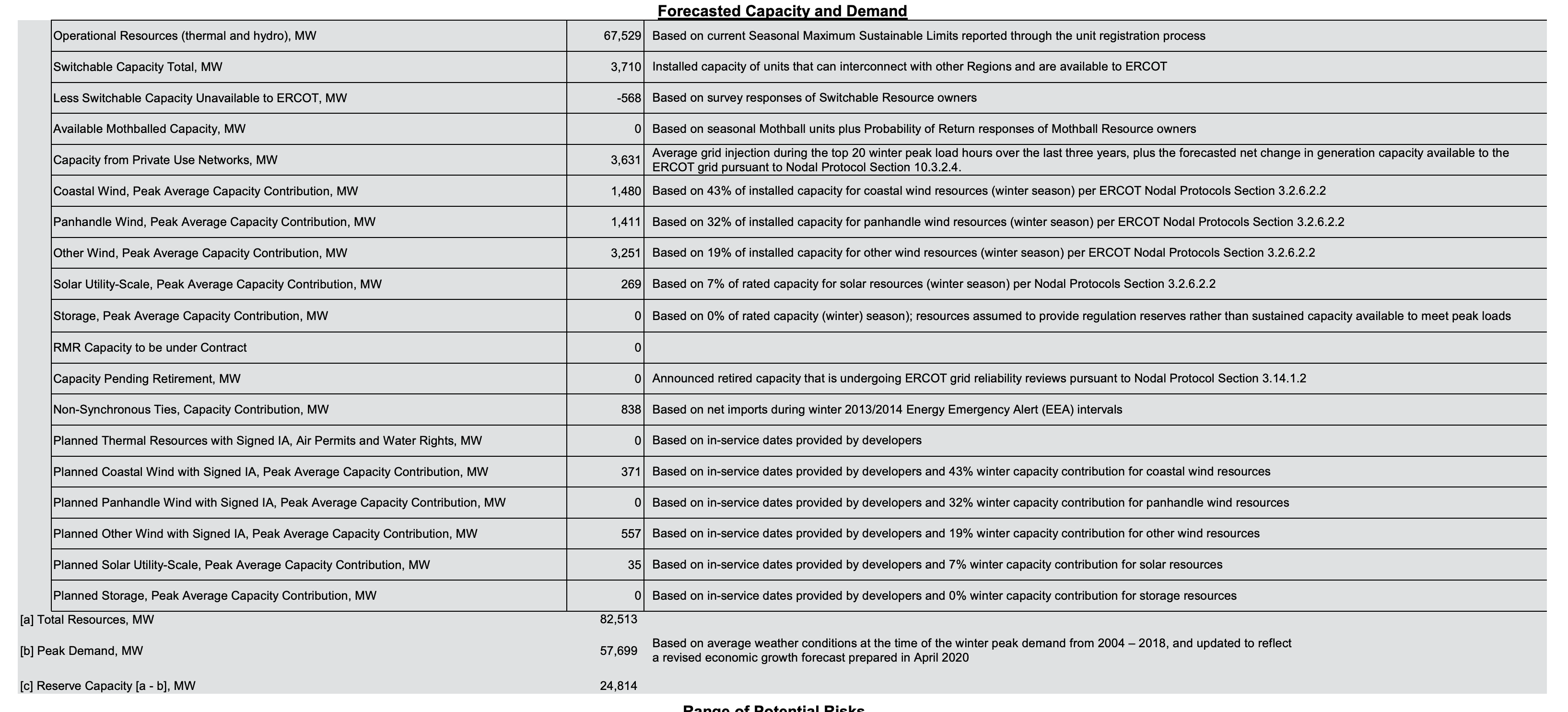

ERCOT knows that those average conditions don’t happen all the time. So before each season, it issues a resource adequacy assessment to be sure the lights stay on when demand peaks. This winter’s plan expected “operational resources” (mostly gas, plus coal, nuclear and hydro) to provide 67 GW of power. Since it’s not always windy or sunny, ERCOT guesstimated just over 6 GW would come from wind and solar combined.

In a “normal” winter, operational resources could have satisfied peak demand, even without any help from wind or solar. Aside from the peak, wind and solar avert emissions while saving costlier fossil fuels for when we’ll need them most.

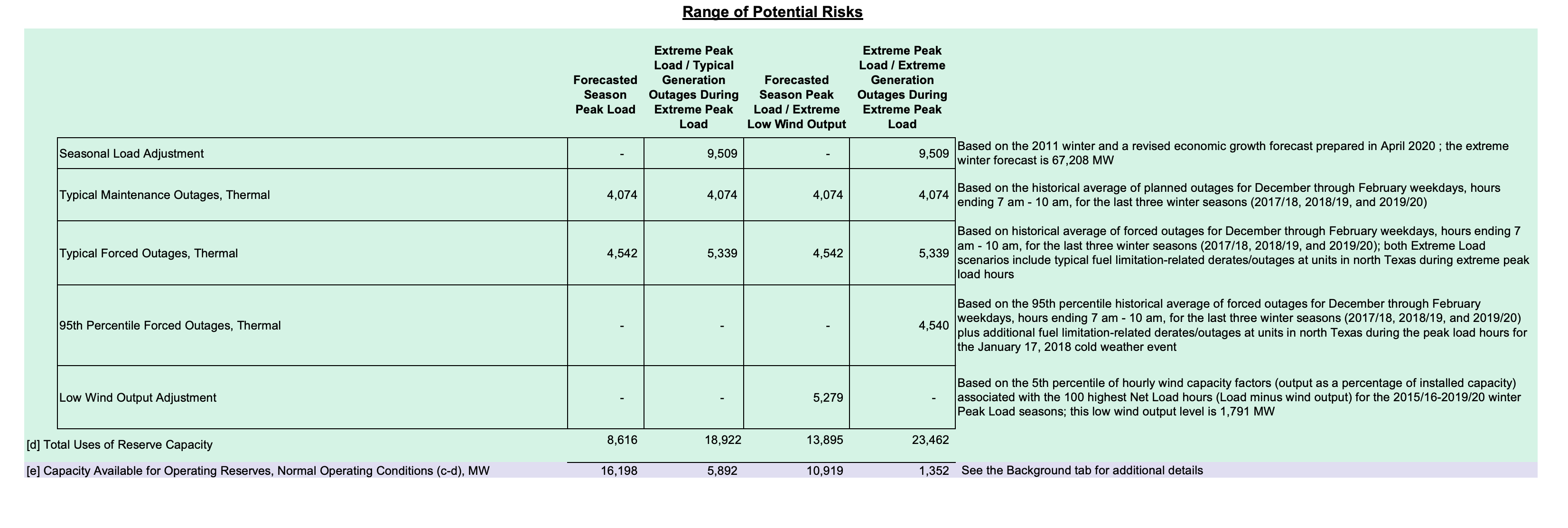

ERCOT realized not every winter is typical, so it planned for several what-if scenarios and associated risks. (All of their estimates are publicly available.)

Those scenarios display the typical temptation to refight the last battle. In this case, that meant planning for a repeat of the 2011 freeze that last caused rolling blackouts. Those lasted just hours, not days, and weren’t nearly as widespread.

Even so, ERCOT didn’t do too badly predicting peak demand — 67 GW in its extreme scenario. We don’t know how high the actual peak would have been without these rolling blackouts, but perhaps around 5 GW higher, with some conservation by industrial consumers.

Scheduled maintenance played a role too, as plants tune up for summer peaks. Why so much of that maintenance continued amid week-ahead forecasts of an Arctic blast deserves a closer look.

But ERCOT’s biggest miss came in preparing for outages at what it thought were “firm” resources — gas, coal, and nuclear. Those outages topped 30 GW, more than double ERCOT’s worst-case scenario. Just one of those gigawatts came from a temporary outage at a nuclear unit. Most of the rest came from gas.

That doesn’t necessarily mean a lot of individual gas power plants broke down. Most outages came because delivery systems failed to supply gas to those plants at the consistent pressures that they need.

These failures highlight the unique vulnerabilities of relying so heavily on natural gas for power. Only gas electricity relies on a continuous supply of a fossil fuel delivered from hundreds of miles away. And that fuel is also needed for heat. So when an Arctic blast drives up demand and drives down supply of heat and electricity at the same time, power plants languish in line while homes and hospitals get the heating fuel they need.

That makes these blackouts an energy systems crisis, not just a power crisis. Every one of our power sources underperformed. Every one of them has unique vulnerabilities that are exacerbated by extreme events. None of them prepared adequately for extreme cold.

But our power system isn’t just failing us in the moment. It’s too costly year-round, not just in dollars but in its impacts on our air, climate, and health. Texas coal plants emit more carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides than in any other state, at a cost of hundreds of lives per year, our research has shown. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has allowed some of those coal plants to avoid installing sulfur dioxide scrubbers, which have been required at all new plants since the early 1980s. Its Regional Haze Plan proposes to do zero about it.

We should be thinking of our electricity supply as a team, or a portfolio of resources. We need that team to collectively be affordable, reliable, resilient, and clean. No single player can do it alone. We don’t necessarily need all players — we can phase out coal with time. But we do need a balanced mix. If we buy into the false narratives of this crisis, we won’t add enough clean sources fast enough to balance the fossil-heavy portfolio of today.

We need investigations into what has become the worst winter blackouts in Texas history, not just uncomfortable but deadly for too many of my fellow Texans. We need to look at systemic failures across energy systems, supply and demand, and the energy-water nexus too. Every one of our sources of power supply underperformed. Every one of them is vulnerable to extreme weather and climate events in different ways. None of them were adequately weatherized or prepared for a full realm of weather and conditions.

We also need to realize that this particular event, an Arctic blast stronger than any in more than three decades, is rare. Climate science is uncertain on the future of extreme freeze events, but on average our winters are getting warmer. Houston gets five times fewer freezing nights than in the 1970s. That means that our next extreme events are more likely to come in the form of heat waves, droughts, hurricanes, and floods, all made worse by climate change.

So whatever we do to improve our energy systems to prepare for the next freeze, we should prioritize measures that add resilience, affordability, and environmental sustainability across a spectrum of typical and not so typical conditions.

With better preparation, rather than political posturing, we’ll be better equipped to keep the lights on and our homes warm whatever weather may come.

Daniel Cohan is an Associate Professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Rice University. His research specializes in the development of photochemical models and their application to air quality management, uncertainty analysis, energy policy, and health impact studies.

They seem to be making progress today according to interview I just heard,seem to be down to 40,000 or so with out power from over a million or so yesterday.

More info

I’ll add this absurdity

No doubt this fact warms the hearts of the remaining 40,000.

Maybe even the heart of Ted Cruz, if he has one.

What is Texas going to do about the billing going forward?

Nice circumspect article. Can’t help but notice the lead is buried a little. Yes all the generating sources faultered, but running out of gas pressure to plants was pretty much what happened. Jeff Skilling is now out of jail, he’s got a new venture started looking for investors in some “digital generation” oil and gas market.

It might only show its white belly when people die, but the crooked pirating and profiteering is baked in.

There has been remarkably little comment on the isolated nature of ERCOT. Most other grid systems have links to broader areas, so the problems in Texas have been more severe than in other places. The isolation of ERCOT is/was a political decision to avoid Federal regulation and dates back to the 1930s and the utility scandals and related regulations. Similarly Texas has had an internal oil and gas market. While Texas is big and somewhat climatically diverse, not enough to counter the systemic risk of an insular market.