This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It first appeared at The Conversation.

Four years ago, I traveled around America, visiting historical archives. I was looking for documents that might reveal the hidden history of climate change – and in particular, when the major coal, oil and gas companies became aware of the problem, and what they knew about it.

I pored over boxes of papers, thousands of pages. I began to recognize typewriter fonts from the 1960s and ‘70s and marveled at the legibility of past penmanship, and got used to squinting when it wasn’t so clear.

What those papers revealed is now changing our understanding of how climate change became a crisis.

On Oct. 28, 2021, executives from Exxon, BP, Chevron, Shell and the American Petroleum Institute faced questions from a Congressional subcommittee about the oil industry’s efforts to downplay the role of fossil fuels in climate change. The industry’s own words, as I found in my research, show they knew about the risk long before most of the rest of the world.

Surprising discoveries

At an old gunpowder factory in Delaware – now a museum and archive – I found a transcript of a petroleum conference from 1959 called the “Energy and Man” symposium, held at Columbia University in New York. As I flipped through, I saw a speech from a famous scientist, Edward Teller (who helped invent the hydrogen bomb), warning the industry executives and others assembled of global warming.

“Whenever you burn conventional fuel,” Teller explained, “you create carbon dioxide. … Its presence in the atmosphere causes a greenhouse effect.” If the world kept using fossil fuels, the ice caps would begin to melt, raising sea levels. Eventually, “all the coastal cities would be covered,” he warned.

1959 was before the moon landing, before the Beatles’ first single, before Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, before the first modern aluminum can was ever made. It was decades before I was born. What else was out there?

In Wyoming, I found another speech at the university archives in Laramie – this one from 1965, and from an oil executive himself. That year, at the annual meeting of the American Petroleum Institute, the main organization for the U.S. oil industry, the group’s president, Frank Ikard, mentioning a report called “Restoring the Quality of Our Environment” that had been published just a few days before by President Lyndon Johnson’s team of scientific advisers.

“The substance of the report,” Ikard told the industry audience, “is that there is still time to save the world’s peoples from the catastrophic consequences of pollution, but time is running out.” He continued that “One of the most important predictions of the report is that carbon dioxide is being added to the earth’s atmosphere by the burning of coal, oil, and natural gas at such a rate that by the year 2000 the heat balance will be so modified as possibly to cause marked changes in climate.”

Ikard noted that the report had found that a “nonpolluting means of powering automobiles, buses, and trucks is likely to become a national necessity.”

As I reviewed my findings back in California, I realized that before San Francisco’s Summer of Love, before Woodstock, the peak of the ’60s counterculture and all that stuff that seemed ancient history to me, the heads of the oil industry had been privately informed by their own leaders that their products would eventually alter the climate of the entire planet, with dangerous consequences.

Secret research revealed the risks ahead

While I traveled the country, other researchers were hard at work too. And the documents they found were in some ways even more shocking.

By the late 1970s, the American Petroleum Institute had formed a secret committee called the “CO2 and Climate Task Force,” which included representatives of many of the major oil companies, to privately monitor and discuss the latest developments in climate science.

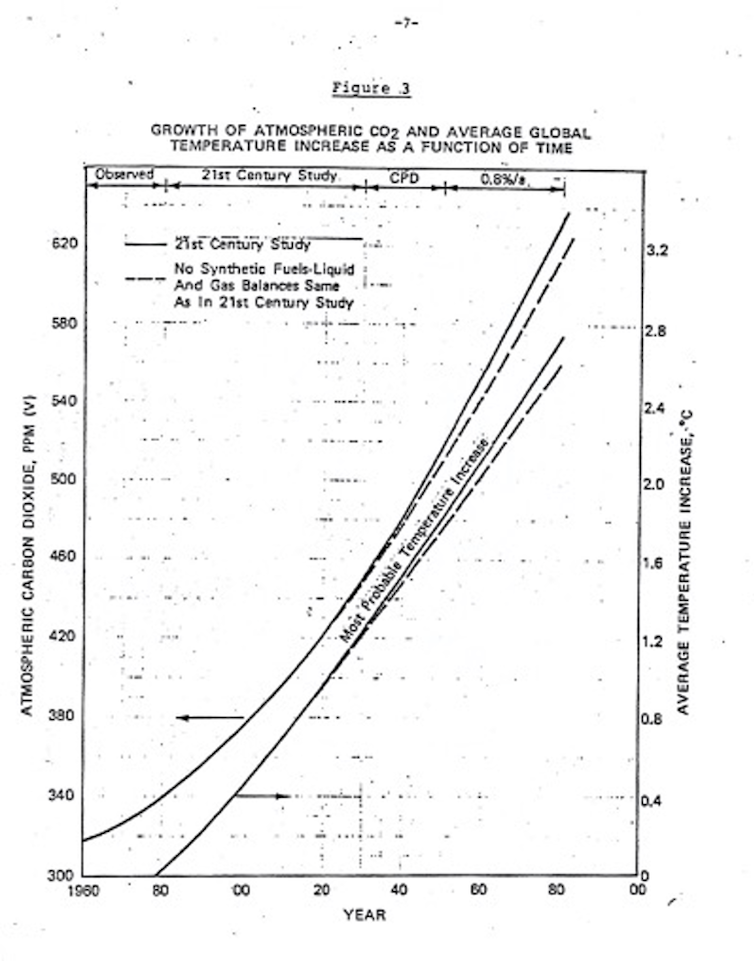

In 1980, the task force invited a scientist from Stanford University, John Laurmann, to brief them on the state of climate science. Today, we have a copy of Laurmann’s presentation, which warned that if fossil fuels continued to be used, global warming would be “barely noticeable” by 2005, but by the 2060s would have “globally catastrophic effects.” That same year, the American Petroleum Institute called on governments to triple coal production worldwide, insisting there would be no negative consequences despite what it knew internally.

Exxon had a secretive research program too. In 1981, one of its managers, Roger Cohen, sent an internal memo observing that the company’s long-term business plans could “produce effects which will indeed be catastrophic (at least for a substantial fraction of the earth’s population).”

The next year, Exxon completed a comprehensive, 40-page internal report on climate change, which predicted almost exactly the amount of global warming we’ve seen, as well as sea level rise, drought and more. According to the front page of the report, it was “given wide circulation to Exxon management” but was “not to be distributed externally.”

And Exxon did keep it secret: We know of the report’s existence only because investigative journalists at Inside Climate News uncovered it in 2015.

Other oil companies knew the effects their products were having on the planet too. In 1986, the Dutch oil company Shell finished an internal report nearly 100 pages long, predicting that global warming from fossil fuels would cause changes that would be “the greatest in recorded history,” including “destructive floods,” abandonment of entire countries and even forced migration around the world. That report was stamped “CONFIDENTIAL” and only brought to light in 2018 by Jelmer Mommers, a Dutch journalist.

In October 2021, I and two French colleagues published another study showing through company documents and interviews how the Paris-based oil major Total was also aware of global warming’s catastrophic potential as early as the 1970s. Despite this awareness, we found that Total then worked with Exxon to spread doubt about climate change.

Big Oil’s PR pivot

These companies had a choice.

Back in 1979, Exxon had privately studied options for avoiding global warming. It found that with immediate action, if the industry moved away from fossil fuels and instead focused on renewable energy, fossil fuel pollution could start to decline in the 1990s and a major climate crisis could be avoided.

But the industry didn’t pursue that path. Instead, colleagues and I recently found that in the late 1980s, Exxon and other oil companies coordinated a global effort to dispute climate science, block fossil fuel controls and keep their products flowing.

We know about it through internal documents and the words of industry insiders, who are now beginning to share what they saw with the public. We also know that in 1989, the fossil fuel industry created something called the Global Climate Coalition – but it wasn’t an environmental group like the name suggests; instead, it worked to sow doubt about climate change and lobbied lawmakers to block clean energy legislation and climate treaties throughout the 1990s.

For example, in 1997, the Global Climate Coalition’s chairman, William O’Keefe, who was also an executive vice president for the American Petroleum Institute, wrote in the Washington Post that “Climate scientists don’t say that burning oil, gas and coal is steadily warming the earth,” contradicting what the industry had known for decades. The fossil fuel industry also funded think tanks and biased studies that helped slow progress to a crawl.

Today, most oil companies shy away from denying climate science outright, but they continue to fight fossil fuel controls and promote themselves as clean energy leaders even though they still put the vast majority of their investments into fossil fuels. As I write this, climate legislation is again being blocked in Congress by a lawmaker with close ties to the fossil fuel industry.

People around the world, meanwhile, are experiencing the effects of global warming: weird weather, shifting seasons, extreme heat waves and even wildfires like they’ve never seen before.

Will the world experience the global catastrophe that the oil companies predicted years before I was born? That depends on what we do now, with our slice of history.

This article was updated Oct. 28, 2021, with the congressional hearing beginning.

Benjamin Franta is a Ph.D. candidate in History at Stanford University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The statute of limitation on fraud begins on date of discovery.

It’s not surprising that the oil companies knew, and knew, and then denied, and denied some more. But what baffles me is that within this time frame of the 50s-80s they also had to know that oil, coal, and natural gas are finite commodities. So why didn’t they get involved in solar farms, wind wind farms, and the like? Wouldn’t not paying a supplier for the raw material needed to create energy make solar and wind cheaper, and thus more profitable for them? And there’s those no pesky oil spills, soot particles, to contend with.

Fraud, criminal or depraved indifference to human life, child endangerment…

Nationalize the fossil fuel companies and subject their assets to civil forfeiture, then do the conversions needed within the government, and be done with it.

‘By then, we’ll be dead and it’s someone else’s problem.’

But, but think of all that money they’d would have made by not paying a second and third party to get the coal or NG to their power plants.

To save that money they’d have needed to spend more money. Corporate executives’ legal obligation to the stockholders means they’re always about the short term.