On the surface, the lyrics of our National Anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” seem very clear —that Georgetown lawyer and part-time poet and songwriter Francis Scott Key saw the American flag flying over Fort McHenry at the entrance to Baltimore harbor during the British Royal Navy’s bombardment of September 13–14, 1814. Because the lyrics say that, it must be the truth. Right?

As usual, like much in history, the full reality about the circumstances of how Key’s composition came about is not quite as straightforward as it appears. Moreover, the religious, gentlemanly Key, a songwriter who truth to say is somewhat of a “one-hit wonder,” said very little about writing the song and whether he really did see the American garrison flag through the two stormy days of smoke and rain during which the British onslaught took place.

Thankfully, Frank Key’s ardent hopes that Baltimore would be spared a mauling by the British as had happened with the enemy’s burning of the public buildings of Washington, D.C., only three weeks earlier, were fully realized. The city was saved! On the morning of September 15, the British fleet of up to 70 vessels upped anchor, after re-embarking their Redcoats, and began down the Chesapeake Bay, never to threaten the city again.

The British commander who superintended the re-embarkation of the troops was Colonel Arthur Brooke, who had taken over from fellow Irishman Major General Robert Ross, who was mortally wounded in a skirmish preceding the Battle of North Point of the afternoon of September 12. Ross was the British commander who had burned the White House. He was also the man who inadvertently set into motion the train of events that would lead to Key writing the lyrics to the future U.S. National Anthem. (Key’s song remained one of a number of popular patriotic songs for the remainder of the 19th century and the first three decades of the 20th until signed into law as this nation’s official anthem by President Herbert Hoover in March 1931.)

The situation in which the lawyer came to write the famous song are fairly well known: Key and U.S. Agent for Prisoner Exchange Colonel John S. Skinner had sailed out from Baltimore aboard a truce vessel in early September to find the British fleet. The two Americans had been sent on a special mission by President James Madison himself, to negotiate the freedom of a captured American. Dr. William Beanes had been detained by the British after he had been involved in the arrest of some British stragglers after the sack of Washington.

Perhaps less well known is that Beanes, who allowed General Ross to use his house on Academy Hill in Upper Marlboro as headquarters prior to the attack on Washington, had been party to an agreement by the town elders to not act with hostility toward the invaders. In return, the British promised to spare the town and to respect the citizens’ property. While the British were in Upper Marlboro, moreover, Dr. Beanes seemed sympathetic to the British cause, in Revolutionary War terms a “Tory” or Anglophile, a British-oriented American. Given the hospitality he displayed to his British guests, the good doctor seemed to the Irish-born general an honorable and excellent fellow. The apparent sudden change in character by the Upper Marlboro physician within a matter of days angered General Ross who felt that the doctor had acted dishonorably by breaking a gentlemen’s agreement. Despite the misbehavior of some of Ross’s own Redcoats, in the general’s view, Beanes had acted treacherously toward his former guests.

In the end, the elderly doctor was let go by the British because Key and Skinner had brought along with them letters from wounded British officers who had been left at Bladensburg. The letters were full of praise for the kind treatment the wounded Brits were getting from their American hosts. This testimony impressed both the general and the admirals. The general agreed that Beanes could be released but only on condition that Beanes, Skinner, and Key would accompany the fleet north to Baltimore for the planned offensive against that city. The three Americans simply could not be allowed to divulge to their fellow countrymen the British plans to assault the city. Note though that, as the British army commander would write to General John Mason, U.S. Commissary General of Prisoners, it was not in the least because of any change in attitude toward Beanes on Ross’s part — he still viewed the Upper Marlboro doctor as a rascal.

Thus Key witnessed the terrifying 25-hour bombardment of the fort by five British bomb ships and a rocket ship firing fiery Congreve rockets (“the rockets’ red glare”). The bomb ships could hurl an iron mortar shell packed with black powder some two miles — in fact, the distance to the star fort from the present-day Francis Scott Key Bridge that carries traffic on the Baltimore Beltway I-695 over the Patapsco River. Moreover, to the Royal Navy’s advantage, at that distance these specialized mortar platforms were safely out of range of the fort’s best artillery. The song, first titled “The Defense of Fort McHenry” and published originally without Key’s name attached to it, was rushed into print by Key’s brother-in-law, Judge Joseph Hopper Nicholson, a militia artillery captain at Fort McHenry during the bombardment. Because the song so perfectly captured the triumph felt by Americans at the great defensive victory, it became an instant hit and, set to the music of a popular song of the day, “To Anacreon in Heaven,” it was sung by an actor named Hardinge in the city’s Holliday Street Theatre within a month after the bombardment.

|

| The original Star Spangled Banner “Museum” (Library of Congress) |

Now, not too many people are aware that Frank Key had written a song in 1805 following the Tripoli War called “The Warrior Returns” which also references the American flag and that was also set to the same music, often characterized as a British drinking song, but actually more the song of a gentlemen’s social and cultural society. The music for “To Anacreon in Heaven” had been used for the popular campaign song “Adams and Liberty” to support incumbent Federalist John Adams in the 1800 U.S. presidential election in which Adams lost to Republican Thomas Jefferson. To me, this is a strong reason to think that Key didn’t need to see the flag, because he already had a prototype for the new song in mind, and also that he already knew the music to which to set the new lyrics.

How far was Key from Fort McHenry? Despite early illustrations showing an American vessel among or near the British bombardment fleet, is it likely that the British would have allowed the Americans to be that close to their war vessels, and possibly endanger their lives? More likely, Key’s truce vessel, if he was aboard it during the bombardment, was either behind the British bombardment squadron or else all the way back at Old Roads Bay where the British troopships were anchored, some 15 miles downriver.

Thus, whatever distance Key was from the fort, on a stormy and rainy day and night, it would have made it difficult for him to see the flag. To this day, the National Park Service rangers at Fort McHenry don’t fly the big flag during stormy weather. Instead, at such times, they fly a much smaller “storm flag.” The giant, famous 30- by 42-foot flag now treasured at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History on the Mall in Washington did not fly during the bombardment. Rather, it was raised on the morning September 15 as the British ships began to leave the Patapsco. That would have also been when Key on board the truce vessel would have sailed toward the city and seen the big flag flying. There is agreement among historians about that at least—although, as we have discussed, the traditional story, and the words of the song itself, imply that Key wrote the song as the battle was ongoing.

Years ago, historian and NPS Ranger Scott S. Sheads at Fort McHenry told the present writer that the lyrics to the anthem reveal the truth: “The bombs gave proof thro’ the night that our flag was still there.” In other words, because the bombardment was still going on, Key knew it must mean that the American flag was still flying. Yet recently Ranger Sheads has changed his tune (excuse the pun!) citing a contemporary rather naive painting which shows, among the British bombardment fleet, a small sailing vessel with an American flag. And, indeed, there is also some evidence that the British may have wanted Key close to hand in case there were negotiations over a possible surrender of the fort. Perhaps then this rather neat video of the British attack on Baltimore does in fact show the position of Key’s vessel. Look at the blue vessel just behind the British bombardment fleet toward the end of the video.

Dr. John McCavitt, my Northern Irish co-author for our forthcoming book on General Ross — surprisingly, perhaps, the first such book in 200 years about the man who captured Washington! — found an interesting nugget of information that might give us a clue as to where Key was located. Dr. McCavitt, who actually lives in Rostrevor, Northern Ireland, General Ross’s home village, runs a website about Ross. He discovered in an obscure magazine a reminiscence written by a Frederick lawyer who knew Key. The lawyer’s recollection might tell us the Georgetown man’s location during the bombardment.

Lewis Penn Witherspoon Balch (1787–1868), later a judge on the State Circuit Court of West Virginia, wrote in an 1863 magazine article that he recalled that Key told him that he had been on board British Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane’s flagship, and that he saw the corpse of General Ross being carried solemnly on board. This would have been on the afternoon or evening of September 12, before the famous bombardment began the very next morning. It is known that the body of the dead British commander was taken back to the original landing place of the British in Old Roads Bay, that is, present-day Fort Howard south of Edgemere, Baltimore County.

Does that mean that Key stayed at that location aboard the British flagship the entire time? Or did the Georgetown lawyer, the composer of the lyrics for America’s most iconic song, in fact move closer to the bombardment squadron aboard his truce ship to negotiate the surrender of the fort, if that unfortunate-for-America development should have taken place? In which case, he probably would have had a perfect view of the famous bombardment, and of the flag, be it the small storm flag or the larger, giant flag now at the Smithsonian.

Christopher T. George is the author of Terror on the Chesapeake: The War of 1812 on the Bay published by White Mane in 2001. He has written a biography of British Major General Robert Ross with Dr. John McCavitt of Rostrevor, Northern Ireland. The book will be published by the University of Oklahoma Press in their “Campaigns and Commanders” series next year. As a historian, Chris is featured in an hour-long Maryland Public Television documentary, “F. S. Key and the Song that Built America,” which is running in syndication on Public Television stations across the country.

—

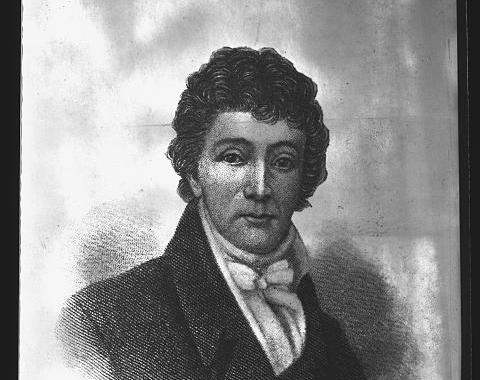

Photo: Francis Scott Key (Library of Congress)

Interesting timing in that I just saw the original flag three days ago while vacationing here in D.C. Not sure I buy some of e speculative leaps in the article, but an interesting read.

You lose the the story in extraneous details.

I think it’s padding. How else do you write long-form article about almost nothing?

More importantly, why did he write a song with a 4 octave (at least) range that is almost impossible to sing?

National Anthem should be American the Beautiful.

I just have to point out that cannon shells in 1813 were not “filled with dynamite.” They were filled with black powder (“gun powder”) which is less powerful than dynamite which wouldn’t be invented for another half century.

Where did you read the ‘filled with dynamite’ quote you are referencing? I didn’t find that in the story.