This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. The following is an excerpt from A Collective Bargain: Unions, Organizing, and the Fight for Democracy (Ecco, on sale Jan. 7, 2020).

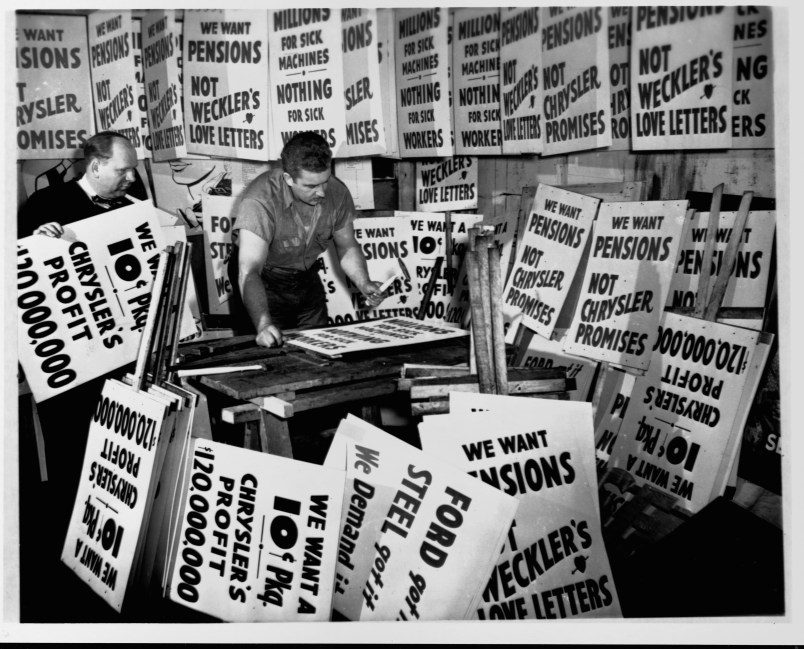

Workers who fought to build strong unions turned horrible jobs in the auto factories into the kind of employment that became the backbone of the American Dream. Liberals yearn nostalgically for a time when corporate leaders seemed more responsible, for an era when CEOs seemed to understand that employees, the people who make the profits, were considered more important than, if not equal to, the shareholders. Elite thinkers today seem to think the CEOs of the inter- and post-war period actually cared about “their” workers. But the “leadership role” CEOs once played, like the corporate culture liberals yearn for, was produced by the power of workers on strike. It’s workers, through their unions, who played the leadership role.

By 1947, just twelve short years into many American workers having the freedom to wage effective strikes, the Northern big business elite chose to ally with Jim Crow racists in Congress, and pooled their money and power into eviscerating those freedoms — outlawing the most effective strike weapon, the solidarity strike — when they passed the Taft–Hartley Act or the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947. Even so, the gains made in just twelve years were so strong that they lasted until the early 1970s, when the employers began a second major offensive, increasing tenfold the number of union-busting firms and weaponizing trade and “globalization” — taking direct aim at the 56 percent unionization rate in American factories.

For another forty years, until the 2010 midterm elections (when Scott Walker passed a series of sweeping laws to systematically dismantle public-sector unions in Wisconsin), public-sector unionization — which also kicked off with a decade of strikes from the late 1960s through the late 1970s — was enough to sustain a decent standard of living for public servants. But we often glance over how public-sector unionization helped all workers because, even as workers in the private sector were being hammered overall, union financial contributions in elections continued to help balance the power of corporate wealth. Even though 1978 was the final year that workers, through their unions, matched big-business donations in national congressional elections, pro-worker Democrats were still receiving sizable union contributions and winning elections. To the Koch brothers and their ilk, this meant that corporations had to find a strategy that could attack the legal system outlined by “states’ rights,” because — unlike private-sector unions — public-sector unions are governed by state, not federal, laws.

Those rights are something in which the Kochs and the right wing believe, except when they don’t: “states’ rights” is the rhetoric first devised by segregationists in the South in defense of slavery, and it’s trotted out whenever convenient, such as in debates about gun rights. But public-sector unions are governed by state laws, not a single national law like the one that controls the private sector. Big corporate interests had to hatch a different strategy, based on a different power analysis.

Thus the Koch brothers and other billionaires launched a plan to maneuver a union attack in states in which the Koch brothers and the right can’t win the kind of slash-and-burn state legislative assault Scott Walker got away with in Wisconsin. A December 2018 article from the right-wing Heritage Foundation read, “Assuming that an average union member pays $600 in annual dues or agency fees, public-sector unions collect around $3 billion a year from the 5 million unionized employees in the 22 states where agency fees were legally permissible. Ninety percent of those employees are located in 11 states — California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Washington,” and Oregon, Illinois, and other states where public-sector unions were strong. Clearly, these billionaires have been scheming to take down today’s public-sector unions.

Taking advantage of the changing Supreme Court, they engineered three successive legal cases, each one nibbling at public-sector union law, each laying the foundation case by case for the coup de grâce, the Janus decision in June 2018. Janus determined that workers in government-sector unions can’t determine, even by majority vote, that their coworkers shall have to contribute either dues or a lesser fee, called agency fees, to their union, fabricating an argument that contributing to the union constrains free speech, as outlined in the First Amendment. Corporations had to manipulate the process to attack the public sector in similarly clever but different ways from when they set out to destroy the private-sector unions. They sought to offshore the most heavily unionized jobs in the 1970s as they increased spending to fight unions workplace by workplace. Today, driven by Silicon Valley, they are weaponizing technology, using AI and robots not only to help rid the country of the remaining unions but — hell — to eliminate the need for workers at all.

The conventional narrative about union decline places most blame on globalization and technological changes. These two forces of change are presented as facts of life and are considered somehow neutral, structural, inevitable. But humans — mostly white, wealthy men who can buy their access to decision makers — are behind every decision regarding robots, trade, workers, and unions (and the planet, too). Like the decision made by executives in Silicon Valley icon Apple, who began the assembly of iPhones in factories in China, where most iPhones are still made and where real unions — that’s independent unions — are forbidden.

A big innovation that’s not pictured in Apple’s slick-hip-cool ads with people dancing with their iPhones is the suicide net. Yes, in China, in the Foxconn factories where one million workers assemble iPhones cheaply so that Apple executives and top shareholders can live like kings, so many distraught workers try to jump to their deaths that the company had to strategically hang nets throughout the plants to prevent suicide. Uber and Lyft can also be dinged with the iSuicide claim: eight taxicab drivers in New York City killed themselves because their once-profitable taxicab medallions are now valued at $200,000, down from $1 million. This kind of despair is the real outcome of the disruptor-billionaire Party of Inequality.

There’s nothing neutral about suicide nets; there’s nothing inevitable about creating a greater climate crisis by offshoring jobs so ships bigger than small towns cross oceans, killing the ecosystem and creating a need for more fuel; there’s nothing comforting about creating millions of close-to-slavery working conditions in faraway lands that Americans can’t see when they happily upgrade to the latest phone. We don’t need robots to care for the aging population. We need the rich to pay their taxes. We need unions to level the power of corporations.

As the Parkland youth say, I call bullshit.

Jane McAlevey is an organizer, author, and scholar. She is currently a Senior Policy Fellow at the University of California at Berkeley’s Labor Center, part of the Institute for Labor & Employment Relations. This piece is excerpted from her new book A Collective Bargain: Unions, Organizing, and the Fight for Democracy (Ecco, 2020).

For Repubs: Communism: Bad, Oligarchy: Good.

While I agree with nearly everything in the author’s take on the history of the mid-late 20th c. labor efforts, and the protracted and organized assault from the right and corporate-capital interests on worker’s rights, having yet another voice - especially such a qualified one - that only berates, but doesn’t provide any insight to how we might make headway toward the stated goals of getting “the rich to pay their taxes” and “unions to level the power of corporations”, is frustrating at best. I still remember the vocal anger toward union and labor action back in the 80’s, when our graduate students were organizing and striking for a decent wage and recognition of their work. The dynamic hasn’t changed, and we haven’t yet seen an effective counter-strategy that is changing the conversation.

Any thoughts on making some “real” change - instead of just ranting at the status quo, and shaking our fists at clouds?

Add to that 70 years the 40 years that “Democrats” have been actively hostile to the needs of workers, beginning with Jimmy Carter in the 1970s with deregulation, through the 2010’s, where Barack Obama still hasn’t found his pair of comfortable picket-walking shoes, and up to Joe Biden, who has assured his CEO friends that his election means that “nothing will change” for them…

The cure would have to involve funneling a lot more money to liberal think tanks to counter the right-wing notions that extreme concentration of wealth is respectable and that workers have no rights. You have to make it respectable again among people high and low to question the system. And you would have to replace doctrinaire right-wing judges in federal courts. It’s going to take time and a considerable investment.

What the author left out was the actual struggles that were the impetus of creating a critical mass of people willing to forswear some immediate compensation for the possibility of better pay in the future. And that history is replete with a significant amount of bloodshed and violence.

In other words, the working conditions of those workers was dire enough that they put their life and limb on the line.

So the question becomes what today is of sufficient magnitude for workers, that they will be of like mind to endure what will be an almost equal power arrayed against those efforts to unionize. Maybe it won’t come in the form of Police goon squads, but as the author alludes to, Corporations have much better tools at their disposal.

Therein lies the rub. The economic dynamics are different enough, that I don’t believe you can expect any true grassroots success of union building. Those efforts are going to have to come externally.

That’s why I look at a Tom Steyer and wonder why someone who has his heart and money being used for progressive causes, doesn’t see how helpful that kind of money could be the difference in providing a floor for a resurrection of unions.

Yes let’s have the rich pay their far share in taxes, but that doesn’t bring up the living standards for the rest of workers.