JUGGLING THE EUROPEAN CRISIS, battling with Congress to arm the Allies, and conducting his “softly, softly” campaign for a third term took a tremendous toll on the fifty-eight-year-old Franklin D. Roosevelt’s health. In February 1940, his devoted assistant Missy LeHand and William Bullitt believed he suffered a minor heart attack over dinner in the White House, which he shrugged off as indigestion. Instead of slowing down, he quickened his pace.

In order to work at his desk longer, Roosevelt started going to bed an hour later and reduced the daily swims that eased his polio to three times a week. He appeared immune to the sweltering heat of the Washington summer of 1940, insisting, because of a recurring sinus condition, that instead of air conditioning he should loosen his tie, roll up his sleeves, and be cooled by a single electric fan.

Unable to spare the time to travel to Hyde Park, where he could best relax, and rationing trips to Warm Springs, Georgia, where he frolicked with fellow polio sufferers in the outside pool, he found he could recharge if he slept overnight on board his yacht, sailing up and down the Potomac. “As long as he has this capacity for a quick come-back, there seems to be no limit to his endurance,” said LeHand.

Unable to spare the time to travel to Hyde Park, where he could best relax, and rationing trips to Warm Springs, Georgia, where he frolicked with fellow polio sufferers in the outside pool, he found he could recharge if he slept overnight on board his yacht, sailing up and down the Potomac. “As long as he has this capacity for a quick come-back, there seems to be no limit to his endurance,” said LeHand.

As Hitler was turning his attention to confronting Churchill’s defiance, the president decided to retool his cabinet. Roosevelt and Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau had hit upon a ruse to outflank the remaining neutrality laws and supply Britain and France by having the War Department return “obsolete” warships and warplanes to their suppliers in exchange for new. The out-of-date equipment, including three-year-old B-17 “Flying Fortress” bombers, could then be legally sold to Britain and France.

Secretary of War Harry Woodring, however, an unrepentant isolationist, insisted that such deals be referred to the War Department for assessment, causing delays and often eliciting a verdict that as the equipment was by no means old nor surplus enough to require replacement it could not therefore be sold to the Allies. Matters came to a head on June 17, when Woodring vetoed the sending of a dozen Flying Fortresses to Britain. Roosevelt dismissed him.

In his farewell letter to Woodring, Roosevelt said he needed to make “certain readjustments” that were “not within our personal choice and control.” In a last gesture of defiance, Woodring leaked to isolationist senators a letter he had written to the president deploring the pressure he was being put under to supply Britain with warplanes. Roosevelt responded to Woodring, “The record shows that you have evidently some slight misunderstanding of facts and dates” and warned him off causing further trouble.

“Doubtless many efforts of mere partisanship in these days, when we should be thinking about the country first, will be directed to having you appear before Committees in order to stir up controversy,” Roosevelt wrote. “Partisan efforts of such a nature not only stir up false issues but do much to retard the progress of the defense program.” Woodring declined the president’s offer of the governorship of Puerto Rico and retreated back to Kansas.

That was not quite the end of the matter. The chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee, Senator David I. Walsh, an isolationist from Massachusetts, spurred on by the anti-British sentiments of his Irish American constituents, led Congress to amend the defense appropriations bill to ban the private sale of arms to foreign governments unless the chief of the General Staff (by this time George Marshall), and the chief of Naval Operations (currently Admiral Harold R. Stark) specifically deemed them of no importance to America’s defense. By this ruse, the isolationists managed to interrupt the sale of twenty new torpedo gunboats to Britain.

Polls confirmed Americans’ continued reluctance to enter the war on the British side, a June 25 Gallup poll finding that 64 percent of Americans thought it more important to stay out of the conflict than to help Britain. In Washington, however, Lord Lothian, by now the British ambassador, sensed that the administration was about to offer Britain certain support, even if it meant going to war. It “would take very little to carry them in now—any kind of challenge by Hitler or Mussolini to their own vital interests would do it,” he wrote to Nancy Astor.

To wrong-foot the Republicans, just five days before they gathered in Philadelphia to pick their presidential candidate, Roosevelt reshuffled his cabinet, turning his administration into a bipartisan “national” war government. Woodring was replaced by Henry Stimson, who had been President Taft’s secretary of war and Hoover’s secretary of state—a man of impeccable foreign and military credentials. Frank Knox, the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936 and a staunch and vocal opponent of isolationism, was appointed navy secretary.

The reshuffle only added to the Republicans’ difficulties. The Democratic leadership had scheduled their convention in Chicago for July, allowing them to make their pick knowing whom they would be running against. The Republican race had come down to three: the frontrunner, Thomas E. Dewey, the thirty-seven-year-old district attorney of New York who was an efficient administrator and an internationalist liberal Republican; Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio, fifty, the staunch conservative and committed isolationist son of President William Howard Taft who had led opposition in the Senate to the New Deal; and Wendell Willkie, forty-eight, a liberal Republican internationalist businessman from Indiana who was the head of the country’s largest utility holding company, Commonwealth and Southern. The son of Central European immigrants, with a German-born father, Willkie was a first-class retail politician and a natural broadcaster who enjoyed an easy rapport with delegates.

According to historian Richard Norton Smith, “Willkie looked like a bear. He was a great big larger than life, rumpled, wrinkled figure who nevertheless had an aura.” He was a loyal Woodrow Wilson self-styled “liberal Democrat” until October 1938, when his dislike of the New Deal’s economic interventionism caused him to switch parties. His career as a faux-populist corporate Republican sprang “from the grassroots of 10,000 country clubs,” joked Alice Roosevelt Longworth, Teddy Roosevelt’s isolationist niece. Willkie was a formidable, combative campaigner and, in the words of historian Charles Peters, “the most dynamic Republican nominee since the other Roosevelt.”

With a strong and energetic isolationist faction among the Republican Party’s rank and file, Taft should have walked away with the nomination, but he looked starchy and his stilted speaking style, so suited to the Senate chamber, failed to spark enthusiasm. Dewey’s Michigan background and his successful campaigns against corruption in New York City gave him an early lead. However, his youth and lack of experience—which allowed Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes to crack that he had “thrown his diaper into the ring”—counted against him. By May of election year, 1940, the bloom was coming off Dewey’s campaign and Willkie, backed by Time magazine’s owners, Henry and Clare Boothe Luce, and the Herald Tribune’s Ogden and Helen Reid, started to move up on the outside.

By the time the Republican Convention opened in Philadelphia on June 24, Willkie was gathering momentum. The first ballot was indecisive: Dewey 360 votes, Taft 189, Willkie 105. Strenuous campaigning in the hall by Willkie supporters translated by the fourth ballot into a Willkie lead that by the sixth and final tally, on June 28, saw him crowned Republican champion for 1940. To balance the ticket, Senator Charles L. McNary from Oregon, a progressive, largely pro-New Deal Republican, but, all importantly, an isolationist, was chosen as Willkie’s running mate. Triumphant, Willkie embarked on the yacht of Roy Howard, the isolationist publisher of the Scripps–Howard newspaper chain, which ferried him lazily back to New York.

When the Democrats gathered in Chicago on July 15, Roosevelt had so confused the contest for the nomination that only a couple of competitors remained: John Garner and James Farley. Neither enjoyed anything like the stature, nor had the political skills, to rival the president, whose command of the party appeared absolute. His remaining aloofness from the contest served three purposes. It showed that clamor from the party, not personal ambition, drove his campaign for a third term. It demonstrated that the war in Europe ad reached such a critical point that Roosevelt could not spare time for partisan matters. And it allowed the president to appear lofty and remote, ensuring that he would only accept the candidacy on his terms and with a hand-picked running mate.

A week before the convention opened, Roosevelt took the precaution of inviting Farley, as chairman of the Democratic National Committee, to Hyde Park in the hope that he would stand aside. According to Farley, the president told him, “Jim, I don’t want to run and I’m going to tell the convention so.” Taking the president at his word, Farley said, “If you make it specific, the convention will not nominate you.” Farley told the president that he was against a third term on principle and that there were at least two good candidates ready to take his place. “The smiles were gone,” recalled Farley.

“I said . . . he had permitted, if not encouraged, a situation to develop, under which he would be nominated unless he refused to run . . . [and had] made it impossible for anyone else to be nominated, because . . . leaders were fearful they might be punished if they did not go along with him.” Farley said that Roosevelt should follow the example of William Tecumseh Sherman, who declared in 1884, “If nominated, I will not run. If elected, I will not serve.” Farley gleaned from the president’s face that he had every intention of running. “Jim, if nominated and elected, I could not in these times refuse to take the inaugural oath, even if I knew I would be dead within thirty days.”

When the convention began in the Chicago Stadium, the largest covered arena in the world, those who backed Roosevelt simply wanted to get the deal done. Supporters of Garner, Farley, Cordell Hull, and others, meanwhile, hoped for a feisty debate followed by a series of close ballots. These opponents of the president were irritated to discover that what they were attending was not an election but a coronation masterminded by the invisible hand of Harry Hopkins from a suite in the Blackstone Hotel, where he had installed a direct telephone line to the White House. The president’s loosely arranged strategy team in Chicago consisted of James F. Byrnes, Ickes, and Frances Perkins. A key player was Chicago’s mayor, Edward Kelly, a master machine politician who had been recruited to manipulate conditions in favor of the president.

Early on, Knox’s Chicago Daily News began reporting that the renomination of Roosevelt was likely, but that delegates would back the president “with the enthusiasm of a chain gang.” Hopkins was failing to marshal the president’s allies. “Harry seems to be making all his usual mistakes. He doesn’t seem to know how to make people happy,” said Eleanor, listening to the convention on the radio in her cottage in Val-Kill above Hyde Park.

U.S. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt waves as she acknowledges a standing ovation after she addressed the Democratic National Convention at Chicago, Ill., July 18, 1940. The DNC chairman Alben W. Barkley stands behind her. (AP Photo)

U.S. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt waves as she acknowledges a standing ovation after she addressed the Democratic National Convention at Chicago, Ill., July 18, 1940. The DNC chairman Alben W. Barkley stands behind her. (AP Photo)

Matters took a turn when isolationist senators Wheeler, Walsh, and Bennett Clark, joined by Woodring, proposed an amendment to the party platform that “We will not participate in foreign wars and we will not send our army or navy or air force to fight in foreign lands outside of the Americas.” Through Byrnes, the president insisted that the senators add the key words “except in case of attack.” Hopkins came to the conclusion that only the arrival of Roosevelt himself in Chicago would guarantee his selection.

Roosevelt resisted. The president “expected the convention to be a drab one and was satisfied with the way that it was going,” Hopkins reported to Ickes and Byrnes. “He didn’t want anything done to disturb the regular procedure.” But Ickes soon became anxious that the convention was careening out of control, telling Hopkins that “if the Republicans had been running the convention in the interests of Willkie, they could not have done a better job.”

Ickes sent Roosevelt a cable. “This convention is bleeding to death and your reputation and prestige may bleed to death with it,” he wrote. “There are more than nine hundred leaderless delegates milling around like worried sheep waiting for the inspiration of leadership that only you can give them.” He predicted that if “the Farley–Wheeler clique” had their way, “a ticket will emerge that will assure the election of Willkie, and Willkie means fascism and appeasement.” He appealed to Roosevelt to accept his historic responsibilities. “A world revolution is beating against the final ramparts of democracy in Europe,” he wrote. “No man can fail to respond to the call to serve his country with everything he has.”

Perkins was also anxious and called the president, telling him about “the bitterness and crossness of the delegates, about the difficulties, confusion, and near fights. I told him that if he could come out to Chicago it would be a wonderful help.” Roosevelt was adamant that everything would turn out right. “How would it be if Eleanor came?” he asked. Perkins said it would make “an excellent impression.” “Eleanor always makes people feel right,” he said, and asked Perkins to invite his wife so that the idea did not appear to come solely from him.

Farley, on his way to the hall to be nominated, was alarmed to hear that the first lady wanted him urgently on the telephone, so he returned Eleanor’s call. “Frances Perkins has called me and insists that it’s absolutely necessary I come to Chicago,” the first lady explained. “Frances doesn’t like the looks of things out there and feels that my appearance would do a lot to straighten things out. Now, I don’t want to appear before the convention unless you think it is all right.”

Knowing how powerful a presence the first lady could be, and what her personal intervention on behalf of the president would mean to his own chances, Farley was lost for words. Then he found himself saying, “It’s perfectly all right with me.” Eleanor pressed the point, saying, “Please don’t say so unless you really mean it.” Farley replied, “I do mean it and I am not trying to be polite.” Eleanor set out for Chicago, asking a friend, C. R. Smith, head of American Airlines, to fly her there in his private plane.

Reinforcements for the president’s cause also arrived in the shape of Mayor Kelly. While Farley kept close control of the gallery tickets, which set the tone of the proceedings, the Chicago police, reporting to Kelly, were responsible for securing the hall. Soon Farley and Garner supporters found it increasingly difficult to gain access to the stadium. In their stead were Kelly’s loyal supporters, under strict orders to chant for the president at every turn.

It fell to Senator Alben Barkley of Kentucky to read a message from the president. Craftily written by Roosevelt’s chief speechwriter, Sam Rosenman, it both denied that he was seeking a third term while encouraging the delegates to demand one. At the first mention of Roosevelt’s name, the stadium erupted in cheers that went on for an hour. When demanding silence, banging his gavel, and calling for order had no effect on the cacophony, Barkley claimed a doctor was needed to tend to a woman who had been struck down in the mayhem. The ruse worked and the delegates simmered down.

Barkley spoke for a further thirty minutes before reaching the finely worded message the president had asked him to deliver: “The President has never had and has not today any desire or purpose to continue in the office of President, to be a candidate for that office, or to be nominated by the convention for that office,” he said. “He wishes in all conviction and sincerity to make it clear that all of the delegates at this convention are free to vote for any candidate.” The hall fell silent.

Then, from all corners of the stadium came the refrain, “We want Roosevelt!” Adding to the hubbub, Kelly’s police band marched down the aisle in full dress uniform playing Roosevelt’s campaign theme, “Happy Days Are Here Again,” whose chorus was picked up by the organist on the stadium’s giant Wurlitzer. Chicago firemen joined in with a stirring rendition of “Franklin D. Roosevelt Jones,” a popular song from the 1938 musical Sing Out the News, which included the words, “How can he be a dud or a stick-in-the-mud / When he’s Franklin D. Roosevelt Jones?”

This “spontaneous” display of affection and affirmation was coordinated by Kelly, a former chief sanitary engineer of Chicago, who had ordered Thomas D. Garry, the city’s superintendent of sewers, sitting with a microphone in the basement, to belt out “We Want Roosevelt!” over the public address until directed to stop. The orchestrated acclamation continued for an hour.

The following morning’s ballot reflected the overwhelming support for a Roosevelt third term. The president won 946 votes, Farley seventy-two, Garner sixty-one, Millard Tydings, a senator from Maryland, nine, and Hull, whose name was not on the ballot, five. Eager to seem a good sport, Farley gave way and proposed making the ballot unanimous. With Garner humiliated, the interest now passed to potential running mates. Twice in the previous two weeks, Roosevelt had asked Cordell Hull. He now asked for a third time, and for a third time Hull declined. Roosevelt’s second choice was a surprise: Henry A. Wallace, the secretary of agriculture from Iowa, who recommended himself to the president because, although he had been a Republican until 1936, he was a progressive and came from the Farm Belt, where support for Roosevelt was weak.

President Franklin Roosevelt and his cabinet gave serious attention the afternoon of Sept. 27, 1938 to the war-threatened European situation. In foreground, is the President, and on the left hand side of the table, L to R, are Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Attorney General Homer Cummings, Secretary of the Navy Claude Swanson, Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins. On the right are U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hill and Secretary of War Harry Woodring. (AP Photo)

President Franklin Roosevelt and his cabinet gave serious attention the afternoon of Sept. 27, 1938 to the war-threatened European situation. In foreground, is the President, and on the left hand side of the table, L to R, are Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Attorney General Homer Cummings, Secretary of the Navy Claude Swanson, Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace, Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins. On the right are U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hill and Secretary of War Harry Woodring. (AP Photo)

Wallace had drawbacks. He had never stood for elective office, and while he had proved an innovative agriculture secretary, he dabbled with the occult and was considered eccentric in the extreme. Party elders felt that Wallace would not boost the farm vote but was sure to alarm commonsensical northeasterners. Above all, a concern arose that, in light of the president’s ailing health, Wallace was a rash choice as a president-in-waiting. Who knew whether Roosevelt would last the full term? Farley’s judgment about his own suitability to be president was way off, but he remained a fair judge of character. “I think it would be a terrible thing to have [Wallace] as President if anything happened to you,” he had told Roosevelt during their frosty meeting at Hyde Park earlier that year. “People look on him as a wild-eyed fellow.”

Others lined up to be Roosevelt’s successor, among them failed presidential hopefuls Paul McNutt and Garner, Roosevelt loyalist Byrnes, and high-ranking Democrats including Barkley, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, Speaker of the House William Bankhead, solicitor general Robert H. Jackson, House Majority Leader Sam Rayburn, and Jesse Jones, leader of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Wallace was so unpopular that when his name was mentioned, the convention booed. Asked whether he

would support Wallace, Governor Eurith Rivers of Georgia said, “Why, Henry’s my second choice.” Asked who was his first choice, Rivers replied, “Anyone red, white, black, or yellow that can get the nomination.” But Roosevelt, for reasons which even today remainun clear, insisted on Wallace, and, although Eleanor, too, thought him unsuitable, asked her to fix it.

When the first lady rose to speak on July 18, only Wallace and Bankhead remained in the vice presidential race. “We cannot tell from day to day what may come. This is no ordinary time,” Eleanor declared. “No man who is a candidate or who is president can carry this situation alone. This is only carried by a united people who love their country.” As for Wallace, “If Franklin felt that the strain of a third term might be too much for any man and that Mr. Wallace was the man who could carry on best in times such as we were facing, he was entitled to have his help.”

Roosevelt became so worried he would not get his way that he asked Rosenman to write a speech saying that if he did not get Wallace, he would decline the nomination. The president’s belligerent mood soon transmitted itself to Chicago. Byrnes toured the convention asking, “For God’s sake, do you want a president or vice-president?” On the first ballot, Wallace received only 628 out of 1,100 votes, with 459 cast for his rivals. It was barely half the votes, but it was enough. Still, opposition to Wallace remained so vociferous that he was persuaded not to give an acceptance speech lest the hostility reveal itself to the nation.

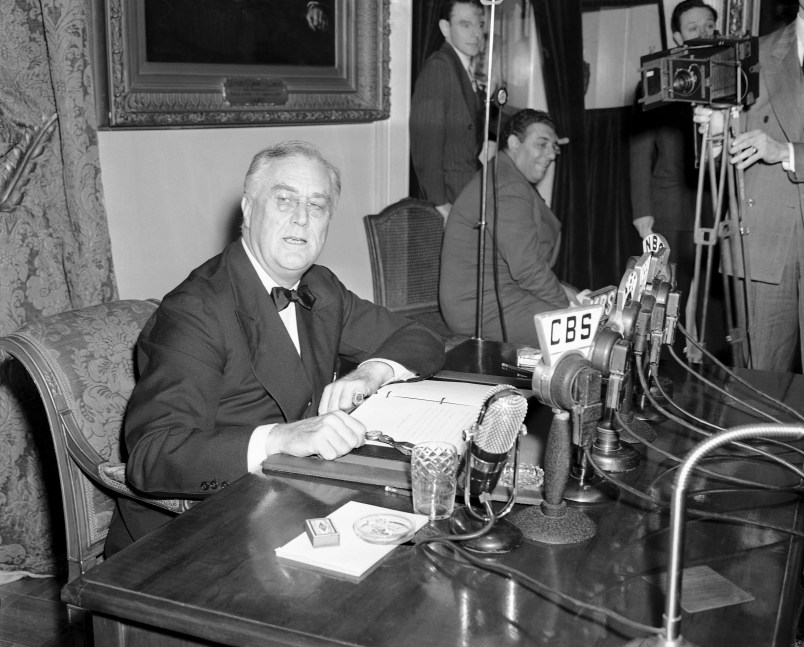

In the White House, long after midnight, a relieved Roosevelt washed, shaved, and dressed, then sat down to deliver his acceptance address by radio to the Chicago delegates. He explained why he needed to stay at the nation’s helm. “During the spring of 1939, world events made it clear to all but the blind or the partisan that a great war in Europe had become not merely a possibility but a probability, and that such a war would of necessity deeply affect the future of this nation.” He said it was “my obvious duty . . . to prevent the spread of war, and to sustain by all legal means those governments threatened by other governments which had rejected the principles of democracy.”

“If our Government should pass to other hands next January—untried hands, inexperienced hands—we can merely hope and pray that they will not substitute appeasement and compromise with those who seek to destroy all democracies everywhere, including here,” he said. As soon as the address was delivered, “everyone got out of Chicago as fast as he could,” recalled Ickes. “What could have been a convention of enthusiasm ended almost like a wake.”’

Reprinted from THE SPHINX: Franklin Roosevelt, the Isolationists, and the Road to World War II by Nicholas Wapshott. Copyright © 2014 by Nicholas Wapshott. With permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Nicholas Wapshott is the author of Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics and Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher: A Political Marriage. A former senior editor at the London Times and the New York Sun, he is now international editor at Newsweek. He lives in New York City.

Just how does this excerpt discuss how FDR “wrangled” the US into WW2? It deals mostly with domestic politics and doesn’t even discuss the efforts to rearm the nation. Besides, FDR never did “wrangle” the US into WW2 but was thrust into by the actions of the Japanese. Even after Pearl Harbor the US did not declare war on Germany until after the Germans had declared war on the US. The Isolationists were mostly winning right up to December 7, 1941. Had Germany done nothing post December 7th, all US attention would have been focused on the Pacific, leaving Germany a much freer hand in the Atlantic and in Europe and Africa. We need either a better excerpt to explain the headline or a headline which describes the excerpt. For now, it’s bait and switch.

Gotta agree, the headline is really crappy click-bait. I wonder how much time Mr. Wapshott spent reading Doris Kearns Goodwin’s far superior “No Ordinary Time,” which should be a must-read for FDR junkies.

Is this long book excerpt meant to be a hint and nudge about how Obama should proceed to revitalize America’s involvement in the Levant and southern Russia?

The isolationists were winning in public opinion, but Roosevelt was winning in terms of supplying Britain and France behind their backs (sometimes in defiance ofthe law or his own cabinet secretaries) prior to Pearl Harbor. Of course, if things had gone worse, he would be reviled as a lawbreaker rather than hailed as a hero for that. US attention was always focused on Europe first and foremost.

Rendezvous with Destiny: How Franklin D. Roosevelt and Five Extraordinary Men Took America into the War and into the World by Michael Fullilove (Author) also addresses this situation and time period.