This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

The massacre of ten Black people in a Buffalo, New York, supermarket by a racist gunman earlier this month has prompted renewed discussion about the white supremacist great replacement theory, which the shooter espoused, and the ways in which it is becoming mainstream on the American right. Replacement theory is not so much a “theory” as a racist ideology used to stoke rage that white Christian culture is under threat by an invasion, engineered by Jews, of non-white foreigners who will both pollute and dilute a nation’s heritage and culture. It is, in other words, standard fare if you watch Tucker Carlson or a Donald Trump campaign rally.

But neither Trump nor Carlson are singularly responsible for bringing it into the mainstream of GOP politics. That was done, decades before, by the architects of the “New Right,” who sought to remake the Republican Party in the wake of the civil rights movement. Several of them were fans of The Camp of the Saints, the racist 1973 novel by the French writer Jean Raspail. The book, which depicts nonwhite migration to France as an “invasion” that overwhelms the white population, has become a bible of sorts for today’s great replacement enthusiasts, including former Trump strategists Steven K. Bannon and Stephen Miller.

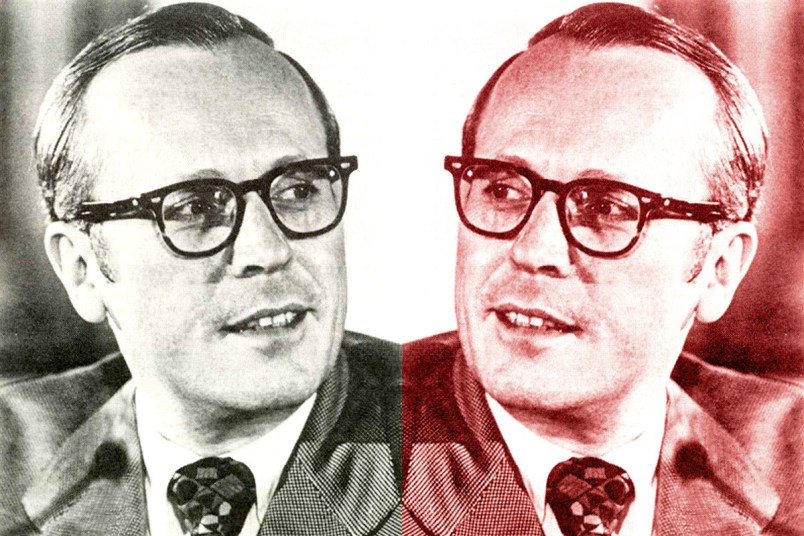

One of the central figures in mainstreaming great replacement theory was William Rusher, who from 1957 to 1988 was the publisher of the iconic conservative magazine National Review. Rusher advocated for a coalition between establishment Republicans and right-wing populists in his 1975 book, The Making of a New Majority Party, which was admired by Paul Weyrich, the top architect of the New Right — and its descendant, the modern conservative movement. With other New Right leaders, Rusher saw the segregationist former governor of Alabama, George Wallace, as an admirable prototype for a presidential candidate.

During this time, Rusher also befriended and advanced the careers of two men who adhered to these ideas, and would go on to become key figures in the later emergence of the alt-right in the early 2000s. This history shows how these ideas were baked into New Right ideology, even as there were episodic efforts by Republican and conservative leaders over the decades to sideline people who expressed them. One more recent example of this whack-a-mole approach is when House GOP Leader Kevin McCarthy stripped former Iowa GOP Congressman Steve King of his committee assignments in 2019 after his long history of racist remarks came to a head. Just a few short years later, Elise Stefanik, the third ranking House Republican whose district includes Buffalo, and who was once considered a “moderate,” has been unapologetically promoting these tropes, even after the Buffalo shooting.

Rusher played a key role in the ascent of Peter Brimelow, founder of the white nationalist website VDare, and a highly visible figure during Trump’s 2016 primary and general election run, when the alt-right cheered on the future president’s nativist campaign. Rusher met Brimelow in the mid-1970s, and the pair kept up a regular correspondence, and saw each other for lunch, dinner, and the opera. In 1978, Brimelow, who at the time was living in Canada, spent a summer in New York City while working as guest editorial writer for the Wall Street Journal, a post he believed Rusher recommended him for.

But Brimelow did not relish multicultural Manhattan, where whites, he complained in a column for a Canadian newspaper, were a minority in the public school system. In the column, Brimelow argued that The Camp of the Saints was predictive of America’s future. To Brimelow, Raspail portrayed “an effete West unable to prevent itself from being overwhelmed by an unarmed invasion of third world immigrants.”

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Brimelow rose through the ranks of conservative politics, working as a policy aide and speechwriter to the late Utah Senator Orrin Hatch, writing for Forbes magazine, and holding a nearly decade-long perch at National Review. Brimelow, himself an immigrant from England, argued that U.S. immigration policy “discriminated against Europeans,” and had “opened the Third World floodgates,” which had “upset” the “ethnic mix” of the country. He warned ominously in a 1992 National Review cover story that by 2020 “the proportion of whites could fall as low as 61 percent.” Many of these arguments were gathered in his 1995 book, Alien Nation: Common Sense About America’s Immigration Disaster. He wrote for National Review until 1997, when William F. Buckley, its editor who had once recommended Brimelow to Rupert Murdoch, vouching for “his solid conservatism,” let him go. Buckley’s betrayal fueled Brimelow’s ongoing resentments of what he calls “Conservatism, Inc.” While he has assailed Buckley, in contrast Brimelow still sees Rusher as a highly effective “nursemaid” of the conservative movement, he told me in 2019.

Brimelow wasn’t a one-off for Rusher. On a spring day in 1975, he met at Washington, D.C.’s Metropolitan Club with Robert Whitaker, a right-wing populist agitator who had a book he wanted to publish. Rusher offered to help Whitaker find a publisher for his racist and eugenicist screed, A Plague On Both Your Houses, for which Rusher wrote the foreword. In the book, Whitaker argued, among other things, that The Camp of the Saints showed that whites would be “doomed to extinction through racial mixture.” Rusher also used his nationally syndicated column to promote the book, at one time calling Whitaker populism’s “spokesman of the first rank,” and citing the book on multiple occasions to argue for a conservative takeover of the judiciary, which he complained “continues to order forced busing.”

Whitaker would go on to work for the late Republican congressman John Ashbrook, and, in 1982, serve as the editor of The New Right Papers, a collection of essays by New Right strategists, including Rusher, Weyrich, and Sam Francis, an avowed racist widely considered to be the intellectual godfather of the alt-right. In a chiling passage in his essay, Francis wrote that the New Right appealed to voters who believed they had a “threatened future and an insulted past,” and that it was “therefore understandable” that they “sometimes fantasize that the cartridge box is a not unsatisfactory substitute for the ballot box.”

Whitaker would go on to work in the Reagan administration’s Office of Management and Budget, and then, in the 1990s, support the Louisiana Senate candidacy of former Grand Wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan David Duke. He faded from public view, only to reemerge in 2006 with his “mantra,” a screed against immigration that claimed there was an “ongoing program of genocide against my race, the white race.” The “mantra” made Whitaker a hero of white supremacists and neo-Nazis. He ran for president in 2016 on the white supremacist American Freedom Party ticket, and died in 2017.

In 2016, I interviewed Brimelow at an alt-right event at the Willard Hotel in downtown Washington. “My key alt-right writers all live here, in the belly of the beast,” he told me. “They work in politics and elsewhere” and in “the government industry,” maintaining “a low profile,” he said vaguely, refusing to elaborate. In the intervening six years it has become apparent that, for the Republican Party, keeping a low profile is no longer required — it is now a big tent for great replacement theory adherents everywhere.

Now do the part where the Zombie Fourth Estate fails utterly from the 1970s onward, not only allowing, but actively facilitating, the GOP’s Southern Strategy/Great Replacement/white supremacist Christian dominionist project of establishing permanent minority-rules hegemony to prevent realization of their wild-eyed existential fears of Mocha Dystopia, including their LITERAL planning for culmination in an End Game whereby victory would be won, come hell or high water, by either rigging the entire system or widespread violence.

Do not forget Murdoch and FOX.

True, but Rusher preceded them and arguably laid the groundwork. Rusher published op-eds (I remember reading him in the Seventies), where he revealed himself to be a complete POS.

While this article does a great job showing is that Donald Trump did not create his base but rather the base of today’s Republican Party created Donald Trump.

However, this article for whatever reasons fails to mention the links between racists and religion, in particular the “Moral” Majority whose founder, Jerry Falwell first rose to prominence in the 1950s for being a staunch segregationist claiming that Black people had “the Mark of Kane” and therefore where by Gods design were inferior to Whites.

The Fucking “MARK OF KANE”.

Falwell continued his screed into the 1960s opposing Civil Rights and school integration, disappeared for a time only to reappear at the 1980 Republican convention where the Party of Lincoln changed its stance on the very issue it was created and changed from being the Party of Lincoln into the Party of Jerry Falwell. That is what caused Falwell to come out of hiding was his anger over Jimmy Carter ending all federal funding for schools that practiced segregation.

Or as has been said many times, the overwhelming support for Donald “grab her by the …” Trump proves that words like “morals” and “values” in front of the word voter is and has always been code for race.

Wait, National Review was a white supremacist publication? My mind is blown.