With immigration reform likely tabled for the rest of 2014, it’s as good time as any to take stock of what we know about how our current immigrant populations and their children are faring in today’s precarious economy.

In my book I explore how the economic incorporation of contemporary migrants and their offspring – especially those from Mexico and the rest of Latin America – mirror or diverge from those of the European immigrant populations of generations past. The successful economic incorporation of Italians, Poles, Russians, and others rested on a context of reception here in the U.S. that included a rapidly growing labor movement.

The growing labor movement provided millions of low-skill immigrants and their children with jobs that paid comparatively well, thus helping to propel whole populations into the rapidly expanding middle-class by the mid-20th Century.

The context of reception has changed dramatically since then. One of the major transformations has been the decline of private sector unions. What this means is that low-skill newcomers today face a labor market lacking the once-common pathway upward, with a result being a “segmented” assimilation pattern whereby many well-educated immigrants and their children move up the class ladder, while less-educated populations languish in jobs providing low pay and little opportunity for advancement. And what it means for ongoing debates about assimilation patterns of contemporary migrants is that the sometimes implicit, sometimes explicit comparison groups that we reference in these debates – the European migrant populations of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries – the relative success of these populations rested on a pretty particular set of economic and political arrangements that have largely broken down.

The context of reception has changed dramatically since then. One of the major transformations has been the decline of private sector unions. What this means is that low-skill newcomers today face a labor market lacking the once-common pathway upward, with a result being a “segmented” assimilation pattern whereby many well-educated immigrants and their children move up the class ladder, while less-educated populations languish in jobs providing low pay and little opportunity for advancement. And what it means for ongoing debates about assimilation patterns of contemporary migrants is that the sometimes implicit, sometimes explicit comparison groups that we reference in these debates – the European migrant populations of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries – the relative success of these populations rested on a pretty particular set of economic and political arrangements that have largely broken down.

In terms of creating and sustaining these arrangements, unions played an outsized role, in spite of the fact that many unions were bitter opponents of opening the country’s borders. The history of the American labor movement is at once a story of inclusion and upward assimilation of previously marginalized groups, and of xenophobic and discriminatory tendencies.

READ: Rich Yeselson responds with “Even Labor’s Best Campaign Isn’t Good Enough”

Immigrants comprised a disproportionate share of union leadership in the early 20th Century, and yet many of these foreign-born union leaders urged politicians to cut off the flow of migrants into the country, while simultaneously fighting the growing foreign influence inside their own locals. Why would immigrants in the labor movement oppose immigration? Many saw rising up the union ranks as a badge of assimilation – as a core part of becoming American (remember this was back in the day when union membership was common). And, having arrived, they acted just as many other Americans did, and fought to keep non-Americans out.

More practically, many within the labor movement feared the destabilizing influence of foreign workers. After all, some employers used immigrant and minority workers as scabs. And even when not being employed as strikebreakers, recent arrivals sometimes proved harder to organize than their U.S.-born peers, often because the economic conditions immigrants experienced here in America compared favorably to the countries they had fled.

The labor movement’s stance toward immigration policies changed right around the turn of the 21st Century. Spurred on by fast-growing unions such as the SEIU and the rise of dynamic leaders such as Eliseo Medina, in 2000 the AFL-CIO’s executive committee issued a statement calling for general amnesty for illegal immigrants in the United States and ending the practice of sanctioning employers for hiring undocumented workers. Announcing that it “proudly stands on the side of immigrant workers,” the AFL-CIO reversed over a century’s worth of lobbying to curtail migration to the United States.

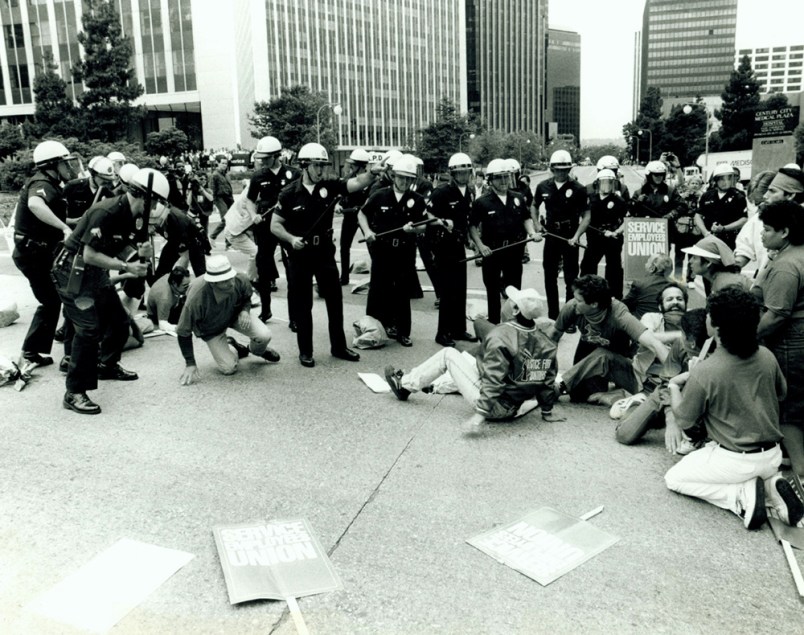

It did so in part because of the rapidly expanding role of Hispanics and Hispanic immigrants in American workplaces, and in unions across the country. And the success of the Justice for Janitors organizing campaign, in particular, where Hispanic migrants – many of them undocumented – proved a formidable force against building owners in downtown L.A. and other U.S. cities convinced many within the movement that new immigrant populations might actually be easier to organize than U.S.-born workers.

And indeed in my book I demonstrate that certain types of immigrants – especially those who have been in the U.S. for at least a few years, and those who have acquired citizenship – have higher probabilities of belonging to unions compared to U.S.-born white workers. Citizenship is a real cleavage, however: comparing workers in the same industry, occupation, and state, I find that the odds of belonging to a union for Hispanic non-citizens, for example, are about a third lower than among U.S.-born whites. Generally, in terms of whether or not you’re likely to belong to a union, it matters much more where you work (public versus private sector; small versus large firm) and what kind of work you do rather than your ethnicity and immigration status.

The Justice for Janitors campaign energized a labor movement desperate for signs of revitalization, and energized progressive forces more broadly (it even lead to a decent film starring Adrien Brody). But here’s the problem: Organizing highly competitive low-skill service industries has always proven exceedingly difficult, all the more so given the country’s broken set of labor laws. This is where the experience of recent immigrants and their children diverges with the experiences of immigrant populations who flooded into unions during the great upsurge in organizing during the 1930s and 1940s. Unlike then, immigrants now encounter a context of reception largely hostile to unionization efforts.

Despite the highly publicized organizing drives of the Justice for Janitors campaigns, the percentage of Hispanic janitors in labor unions has actually declined since 1990, when the campaign scored some of its initial victories, along with the fraction of all janitors who claim union membership. This does not detract from the magnitude of SEIU’s victory, nor should it dampen organizers’ enthusiasms about replicating the tactics and lessons involved in Los Angeles, Houston, and elsewhere.

The union won a series of dramatic victories that resulted in the organization of thousands of disproportionately Hispanic, disproportionately immigrant building cleaners who would not otherwise be unionized. But it ought to temper unions’ and labor researchers’ expectations about what the campaign means for labor’s future, and for what role the labor movement may play in the upward assimilation of Hispanics and other minority and immigrant populations. That these victories failed to reverse the broader trend of union decline simply highlights the challenging organizing environment all unions face in the 21st century. Today, only one in seven Hispanic janitors in the United States belongs to a union, down from one in five back in 1988, when Justice for Janitors began.

Part of TPM Book Club For What Unions No Longer Do by Jake Rosenfeld. Copyright © 2014 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Reprinted by permission of Harvard University Press. All Rights Reserved.

Jake Rosenfeld is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Washington, co-director of the Scholars Strategy Network Northwest (SSN-NW), and a faculty affiliate of the Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology (CSDE), the West Coast Poverty Center (WCPC) and the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies. He received his PhD in Sociology from Princeton University in 2007. For more information, please see www.jakerosenfeld.net.