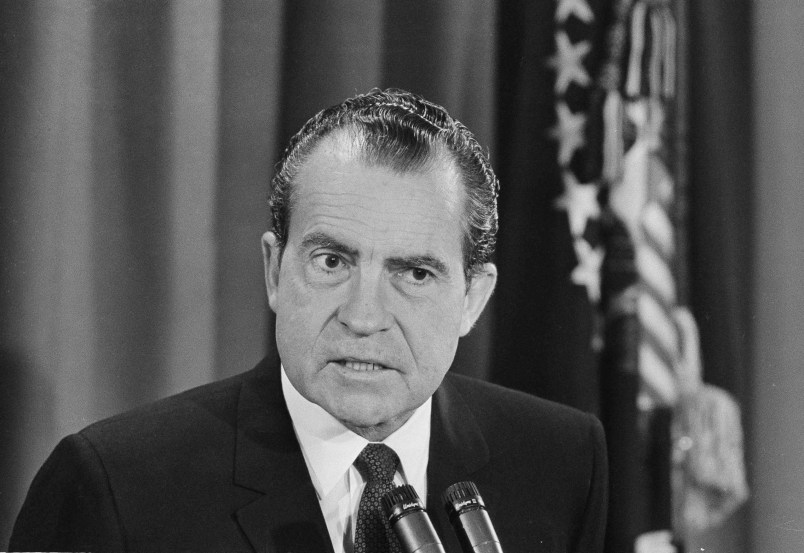

Back in 1971, President Richard Nixon vetoed a bipartisan bill that would have established comprehensive child care centers across the country. To Nixon, this sounded a whole lot like committing “the vast moral authority of the National Government to the side of communal approaches to child rearing.”

Would that Nixon’s rhetoric were just a relic of the Cold War. But less than three years ago, Rick Santorum called early education programs socialists’ attempts to “indoctrinate your children.”

Many conservatives find it intuitive to think of early education programs as something straight out of the European big-state playbook. They hear pre-K and jump straight to French crèches and écoles maternelles. It starts with pre-K, they think, and the next thing you know, American kids will be coming home all over the country preferring Histoire de Babar to The Little Engine That Could.

Yet in reality, early education programs are very much in line with American preferences for market-modeled policies. These days, lots of very prominent people argue that pre-K is an effective public “investment,” because it pays off with gaudy individual and social benefits that can be modeled—and monetized. These comprehensive early education programs are actually hyper-capitalist. They’re neo-liberal. They’re part of a strategy for supporting workers and building a labor force.

Consider the empirical case for expanding investments in early education: these programs increase students’ adulthood salaries, increase students’ likelihood of being stably employed as adults, and make it easier for their parents to work in the short term. The programs also save parents child care costs and decrease the chance that students will make use of public assistance as adults. Some high-quality early education programs make it less likely that their students will grow up to have children out of wedlock, get divorced, or be arrested. Some programs, like Head Start, support better health for their graduates.

Sure, there are structural similarities to other social programs: universal pre-K is to education as a universal single-payer system is to health care. Both are “entitlements” in the sense that they involve government in the project of guaranteeing a social good. Both are, to some degree, in the social democratic project of sustaining meaningful human dignity and freedom by means of government programs. Through this lens, comprehensive early education programs sound a whole lot like Old World big-state socialism.

But there’s a subtle difference between early education investments and other social programs. Look back at the glittering outcomes I listed above: when researchers talk about early education’s “return on investment,” they’re often referring to cost savings that sound relatively friendly to capitalism. These programs support working parents today and lead to more and better work for students tomorrow. They support reduced welfare rolls, smaller prison populations, and healthier workers. In a strange—and welcome—way, early education investments undermine other core priorities of social democratic movements. To put it pithily, more and better pre-K programs can make public assistance less necessary.

The market friendliness of these programs is embedded in the language. High-quality early education investments decrease reliance on other social programs by building human capital. Economists frame the consequences in terms of “return on investment.”

This isn’t a new way of thinking about American education—in 1991, Johns Hopkins University professor Lester Salamon wrote,

For the first time in our history, the nation’s social agenda and its economic agenda seem to have converged. Policies to deal with poverty, drug abuse, employment discrimination, and related problems, which formerly could be justified only in terms of morality or political expediency, have now come to be seen as essential for the nation’s economic progress, as critical investments in its ‘human capital.’

Nor, for that matter, was Salamon the first to appropriate economic framing for public education investments. But forget tracing the rhetoric—we’ve actually tried comprehensive early education investments as part of an economic strategy before.

And guess what? It worked. To borrow Nixon’s evocative language, the United States had already bestowed the federal imprimatur on these programs—just short of 30 years before his 1971 veto.

During World War II, the United States ran a child care system that served over half-a-million children and their parents under the Lanham Act. In particular, the law was designed to support mothers’ contribution to the war effort. If you’ve heard of Rosie the Riveter, that’s some proof of its success. Without someone to watch her children, she never would have made it to the factory.

Child care helped: mom work, the economy boom, and the nation win the war. All in all, a pretty nice haul. But recent research shows that that’s not all. Data suggest that the Lanham Act also contributed to long-term economic returns for students who participated in the program. They were more likely to graduate from high school and reap the increased earnings that come with earning that diploma.

One more thing: there’s a relatively common ethical argument lurking behind fiscal attacks on social programs. Many of these critiques stem from the worry that anti-poverty efforts encourage “moral hazard.” For instance, if these programs ease the indignity of indigence, there’s a chance that they could valorize unproductive, risky, or otherwise bad behavior. What, after all, have high school dropouts or recidivist criminals done to “deserve” support from scarce public resources?

Whatever you think about the validity of this claim or the logic of the arguments it supports (for the record, I find both unconvincing), comprehensive early education programs occupy an entirely different ethical orbit. These serve moral innocents — vulnerable children — long before they make any choices that could legitimate suffering in poverty. No starving five-year-old is to blame for his family’s lack of food. No toddler bears responsibility for her parents’ inability to provide her with picture books. There is no moral hazard for investing public resources in giving children an opportunity to escape from poverty.

So sure, if we look at proposals to expand and align our early education investments in isolation, we can distort them to sounds like any other large public program. But that ignores what makes them unique: high-quality early education actually decreases the size of, and necessity for, other major social investments. They help students grow into healthier, more capable individuals who are prepared to enter the workforce and provide for themselves (and their families). And that sort of self-reliance isn’t socialist, it’s as American and capitalist as the hundreds of businesses supporting increased early education funding through the ReadyNation partnership. If that’s “indoctrination,” then pass the Kool-Aid (and the bipartisan pre-K expansion bill).

Conor P. Williams, PhD is a Senior Researcher in New America’s Early Education Initiative. Follow him on Twitter: @conorpwilliams.