With a Republican Senate majority increasingly plausible, there’s more talk about what will actually happen in an all-GOP-run Capitol next year. What should the Republicans do? House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy suggested they will “prove they can govern.” But many more anticipate the same old standoffs between the Republicans and the president whose second term they tried and failed to prevent.

We may just end up with the worst of both worlds: Republicans will govern by forcing unnecessary crisis. And the deal we’ll get is a pretty bad one.

If you want to know what they will do, look at what they’ve done, and what they’ve said they’re going to do. In 2015 and beyond, a Republican Congress is going to slash the social safety net, or at least attempt to, and they’ll use the same cynical methods they’ve been using to make it happen.

In a great piece on a potential Republican Senate, Molly Ball speaks to Ohio’s Sen. Rob Portman, who insists there’s room for bipartisan agreement and “getting things done” between a Republican Congress and President Obama — including “a ‘grand bargain’ on the budget.”

The term “grand bargain” sounds awfully nice. Here’s what it means, in practice: putting a shiv to the social safety net and getting both parties’ fingerprints on the weapon.

Even though the term sounds polite, a “grand bargain” isn’t incompatible with the kind of loud, showy confrontation that Sen. Mitch McConnell has promised. Remember, the first attempt at a “grand bargain” during the Obama presidency came out of the debt-ceiling standoff of the summer of 2011. Not just big cuts to government programs in general, but big changes to the social safety net, were on the table, including a higher Medicare eligibility age and a new calculation of inflation that would reduce Social Security benefits.

Indeed, whenever you hear murmurings of a “grand bargain,” it’s because some avoidable, manufactured crisis is forcing it — whether it’s funding the government, raising the debt ceiling or averting a fiscal cliff. Republicans are likely to use government-funding showdowns as a weapon to extract safety-net cuts because they already have.

And with a Republican majority, they’ll have lots of avenues to do it, with chairmen like Orrin Hatch at the Finance Committee and Jeff Sessions at the Budget Committee, both strong advocates of policies to privatize, cut and reshape safety-net programs like Medicare. And a Republican majority would include Republican House members like Steve Daines, Tom Cotton, Bill Cassidy and Cory Gardner, who have all voted for budgets that gut Medicare and Medicaid. That’s what they’ve been trying to “get done” for a long time. It’s what they mean by “govern.”

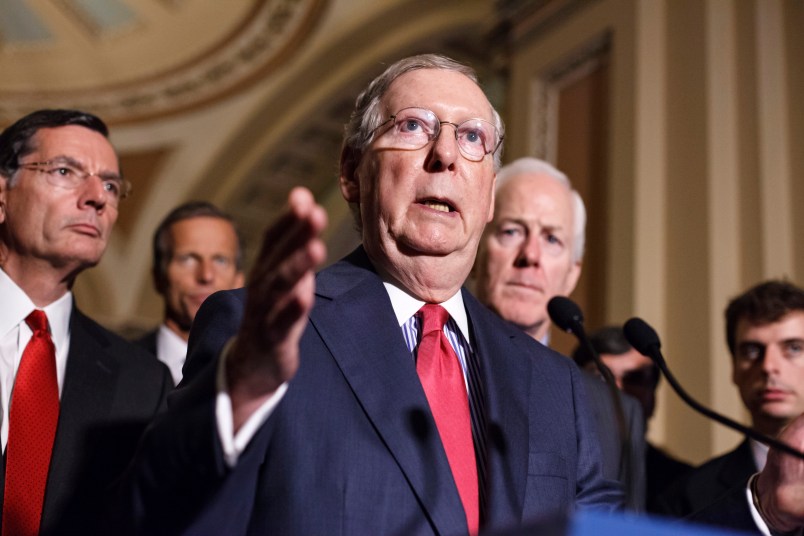

Mitch McConnell is frank about how Republicans are going to get their way:

asked about the potential that his approach could spark another shutdown, McConnell said it would be up to the president to decide whether to veto spending bills that would keep the government open.

Obama “needs to be challenged, and the best way to do that is through the funding process,” McConnell said.

We have to fund government and raise the debt ceiling, and McConnell considers these basic acts of functional governing to be a compromise on his part, so he’ll extract concessions.

For McConnell, using the mechanisms of governing to create crisis points is not inconsistent with “getting things done.” It is “getting things done.”

The reason Republicans need to create crises to attack Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security — and the reason they want President Obama’s signature on the changes — is because what they’re trying to do is incredibly unpopular.

So the next two years under McConnell will be an endless parade of trying to wedge through policies voters don’t want, using the kind of tactics that really turn off voters.

You’d think, then, that the self-appointed guardians of centrism, decency and common sense would be trying to stave off a McConnell Senate. You’d be wrong.

“No Labels,” a group that styles itself as advocates for a “politics of problem-solving,” has endorsed Rep. Gardner for Colorado’s U.S. Senate race, and they’re putting on-the-ground effort behind their endorsement. Gardner, of course, comes from the ever-so-problem-solving Republican House majority, and he’s among the House’s most conservative members. His entry into the race this year has been a vital part of Republican efforts to gain a majority. He’s been a loyal soldier in the strategy of confrontation and crisis, and there’s no reason to think he won’t continue to be.

But there are two reasons why a group like No Labels would put real effort behind Gardner and, by extension, an aggressive Republican Senate.

The first is that, since being anti-gridlock is their brand, gridlock fuels them. “The group is banking on more political dysfunction in an attempt to find ‘opportunity’ and relevance for itself,” reports Meredith Shiner, in an excellent investigation into how the group has become part of the problem it ostensibly intends to solve. No Labels takes in huge amounts of money, gives out meaningless “problem solvers” awards, and strategizes about the “opportunity” created by a Republican takeover of the Senate, all without solving any actual problems.

The second is that, by and large, these groups aren’t really “moderate” in any reasonable sense of the word, and they’re definitely not “non-ideological.” What they represent, instead, is the ideology of elite Washington, which is obsessed with deficits and “tough choices,” and indifferent or hostile to the social safety net. The “bipartisan consensus” that the professional centrists adore is consensus around cutting away Medicare, Social Security and Medicaid.

The point of No Labels and groups like it is to use Americans’ stylistic and procedural moderation as a brand identity for unpopular conservative fiscal policy. They want to cast an ideological position against the social safety net as non-ideological “common sense.”

The “moderation” industry doesn’t want politeness in Washington. They want a set of political outcomes well to the right of what voters want. So it makes sense for them to endorse a conservative Republican who will support a confrontational, crisis-provoking majority leader.

Unfortunately, a Republican Congress might be able to “get things done” on Medicare and other critical programs, and it won’t just be Cory Gardner’s fault.

Republican congressional leaders could “manage to hold things together well enough to cut deals with a weakened Obama,” notes Brian Beutler. “The question is whether moving negotiations between Congress and the White House to the right would make agreements—bad agreements, perhaps, but agreements nonetheless—easier to reach. And there are decent reasons to think it might.”

Molly Ball notes that President Obama “loves the idea of bipartisanship and has been frustrated by a GOP he sees as unwilling to come to the table. He has agreed in principle, in the past, to ideas like the grand bargain.” She also quotes one Democratic aide: “What scares me the most is what Obama will agree to.”

Indeed, Obama almost gave away a huge amount, in principle and in the details, during the 2011 debt-ceiling showdown, and it was only the fanatical intransigence of House Republicans that prevented the deal from going through. “Gridlock,” in that case, prevented a much worse policy outcome from a manufactured crisis.

In order to protect the social safety net in 2015 and 216, we’re going to need some of that gridlock again. Either we have root for the Republican clown-show fringe to disrupt the process (“We as Republicans have a real challenge to get the diversity of our ranks to work together,” Sen. Portman told Ball), or we have to hope that President Obama is willing to stand alone with his veto pen and reject Republican demands.

Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security are some of the great achievements of the 20th century; they keep millions of people healthy and out of poverty. A Republican Congress is dead-certain to go after them aggressively, and ostensibly “centrist” establishment groups are encouraging them.

The best way to avert this spectacle is to get out and vote on Tuesday.

Seth D. Michaels is a freelance writer in Washington, D.C. He’s on Twitter as @sethdmichaels.

Is going from a glacial pace to an absolute standstill the new getting things done?

I’m curious to see how long it will take for Mitch McConnell to eliminate the filibuster completely. It will probably happen the first time Democrats attempt to block legislation.

I’ll put the over/under at March 1.

Must reading!!!

McConnell is what’s wrong with Washington!

Go, Grimes!!!

The only thing we can count on from a GOP congress is political drama that will never end.

If McConnell causes harm to my family, I’m coming for him.