It’s 20-20 hindsight time for pols and pundits, so naturally we are hearing a lot of woulda-shoulda-coulda about the Democratic Party. Never mind that the last election was a second-term midterm with a crazy-positive landscape for the GOP: The defeat was totally avoidable, we are asked to believe, if only Barack Obama and/or the Democratic Party had behaved differently!

Interestingly enough, both “centrist” and progressive critics of Obama and the Democrats seem to agree that they blew it by failing to pay enough attention to the economy, thereby alienating white working class (i.e., non-college educated) voters. Beyond that, accounts begin to differ.

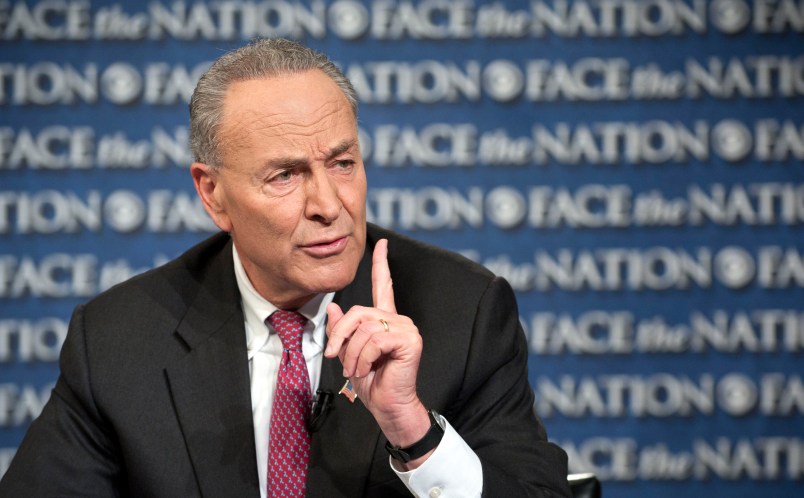

In a much-discussed National Press Club speech last week, Sen. Charles Schumer of New York argued that by prioritizing health care reform, Democrats had elevated the interests of “a small percentage of the electorate”—the uninsured—at the expense of the interests of middle class voters who wanted economic magic. Schumer did not identify exactly what sort of proposals Democrats might have embraced to meet that demand, leading one to suspect he thinks agitating the air on behalf of the desired constituency and its demands might be enough, particularly if combined with a conspicuous decision to abandon the decades-long progressive project of health care reform as a sort of propitiatory sacrifice.

In support of Schumer’s complaint, super-pundit Charlie Cook goes further, arguing that the entire Democratic agenda after the auto industry bailout was a big mistake:

In 2008, we faced the Great Recession, and like other financial meltdowns, it was deep and painful. At the tail end of the George W. Bush administration and in the early Obama years, financial markets were stabilized (the overwhelming majority of the Troubled Asset Relief Program funds have been repaid, with many of the investments yielding profits for Uncle Sam), and the Obama administration should be applauded for rescuing the automobile industry. But while those actions can be legitimately seen as a good start, we then saw a grand pivot to the environment and health care, with grave consequences for the party. At another time and in different fashion, both are important priorities, but the focus on these issues has effectively decimated the Democratic Party in specific areas and among specific voter blocs.

The “rescuing of the automobile industry” both preceded and succeeded the economic stimulus package of 2009, so it’s not clear whether Cook thinks the stimulus legislation is part of the “good” work prior to the “grand pivot,” or not significant enough to be mentioned. In any event, the struggle over the stimulus bill effectively showed the limits of what Democrats could accomplish on the middle-class-economic rescue front even with the swollen congressional majorities they earned in 2008. So again, you have to wonder if the argument is that Democrats should have abandoned their health care and their environmental agendas—both of them longstanding parts of the party’s game plan for governance—in order to “focus on the economy.” But how? Cook’s no clearer on that little detail than is Schumer.

Some left-bent critics of Obama and the Democratic Party do have a specific parallel economic agenda in mind, mostly involving the financial sector: breaking up the largest banks, for example, and perhaps jailing some bankers for their role in the pain and suffering of the Great Recession. That may well represent good policy. And yes, this sort of agenda may have exerted some political appeal. But would financial shock-treatment have had any immediate effect on middle-class incomes? Would it have reduced inequality? And would it have sped up the recovery from the Great Recession? That’s all unlikely. The most-discussed positive policy prescription among progressives, an expansion of Social Security benefits, had less than a snowball’s chance in hell of being enacted by Congress even before, much less after, 2010. And it, too, like the much-derided minimum wage increase proposals of Democrats in the 2014 cycle, and like Obamacare, would have appealed to a relatively small share of voters.

If the point is simply that Democrats would have benefited from a more “populist” political message, that’s easy to agree upon, though it’s not so easy to agree on the components of such a message. You can certainly make a strong case that Democrats were incompetent in conveying their actual accomplishments in economic policy, and the threat Republicans pose to their preservation and extension. For example: how often or well did Democrats explain the Affordable Care Act as an economic initiative? When did they focus on the economic calamities risked by excessive reliance of fossil fuel energy? And in discussing poll-tested policy proposals like a minimum wage increase, to what extent did Democrats nestle these commitments in a broader agenda–that most certainly did exist–of measures aimed at boosting wages and real incomes?

In sum, there are too many variables involved, many of them having nothing to do with policy, to conclude with any degree of precision that a different economic agenda or subordinating health care and the environment to “jobs” would have made a big difference in 2014. And this entire debate is a distraction from what Democrats can do to win in 2016 when they will be in a much better position to hold a comparative “two futures” debate over economic policies instead of a “referendum” on hard times.

Ed Kilgore is the principal blogger for Washington Monthly’s Political Animal blog, Managing Editor of The Democratic Strategist, and a Senior Fellow at theProgressive Policy Institute. Earlier he worked for three governors and a U.S. Senator. He can be followed on Twitter at @ed_kilgore.

Pretty good analysis. Schumer is being a tool, of course.

Our biggest problem is the lack of Democratic voter interest in the mid-terms, which is an institutional, rather than a policy-specific problem.

If the message about how well the economy is improving, and how the Repugnicants threaten that improvement could be broadcast better, that would certainly help, but we face a lot of opposition from a corrupt (Fox) and myopic (the rest) Mediacracy in that effort.

Fear tactics over Ebola and ISIL were highly effective in shutting out good news about the economy and the progress of ObamaCare.

Backstabbing, bitter recrimination, camera-whoring, and above all, many different people contradictorily insisting that if only they had done what the speaker claimed to have said they should do all along, are the traditional Democratic responses to a defeat. Because what is a defeat but an opportunity for self-aggrandizement and self-promotion? (Sadly “we should have listened to what Bob Shrum said we should do and then done the exact opposite” never seemed to make it to the top of the list of “things we shoulda done.”)

Among Republicans, of course, at least since 1976, there are only two approved and acceptable explanations for defeat: a) our positions or candidates were insufficiently conservative and/or b) the election was stolen from us through Democratic voter fraud (i.e. single women and black people were permitted to cast votes in places where their votes mattered).

Wish I could like this 10 times.

Of course, what the Dems really needed was Peggy Noonan blathering on about yard signs.

" this entire debate is a distraction from what Democrats can do to win in 2016 when they will be in a much better position to hold a comparative “two futures” debate over economic policies instead of a “referendum” on hard times."

This. People want to vote for something, the Democrats need to be the positive choice, but not be all wimpy about it. They need to fight back hard on the inevitable wingnut smears.

America is awash in marketing. The Democrats need to hire the best firm and get a coherent campaign going.

Schumer and his corporate pals are not being helpful.

Presidential elections are, by default at least, elections about what one is for. That’s a narrative and motovational frame that generally conforms to the Democratic mindset and thus drives them to the polls where their numerical superiority will make a difference. Midterm elections are necessarily about what you are against and what you are afraid of, a narrative and motivational frame that generally conforms to the Republican mindset and weakens Democratic resolve because they usually just don’t feel fear or rage with the kind of intensity that drives conservatives to the polls.

Republicans always try to turn every presidential election into an election about what you’re afraid of and what you’re against. With the possible exceptions of 1952 and 1956 (though McCarthyism and fear of the USSR loomed in the background of both), Republicans generally only succeed in presidential elections when they succeed, or external events cause, a presidential election to be an election about what voters are against and what they’re afraid of.

It does not seem possible, however, for Democrats to turn a midterm into an election about what people are for, even when that thing is “more of the same.” It just doesn’t motivate their voters because, to the extent things have already been done, they are either disappointed that the ideal they voted for in the last presidential election was tainted by contact with reality or upset that every single thing they wanted done didn’t get done during the preceding two years. Nor do Democrats seem to be able to turn midterms into elections about what Democrats are angry about or what Democrats fear.

Instead, Democrats only seem to be able to prevail in midterms when Republicans, through actions taken by them in the seven to nine months immediately preceding the election and only when they control one or both political branches, manage to turn the election into one about what Democrats are against and what Democrats fear.