Nowadays, the power of the Christian Right is a given. But that wasn’t always the case. In the last 35 years, it’s gone from burgeoning movement to the GOP’s bread and butter. And although its power has waned in the past few years, the last three and a half decades have been remarkably successful.

On August 22, 1980, a massive National Affairs Briefing organized by preacher James Robison brought 15,000 evangelicals to Dallas to demonstrate their newfound political clout. Robison, who had been forced off the airwaves after he claimed that gays recruit children for sex, announced that day, “I’m sick and tired of hearing about all of the radicals and the perverts and the liberals and the leftists and the Communists coming out of the closet. It’s time for God’s people to come out of the closet.”

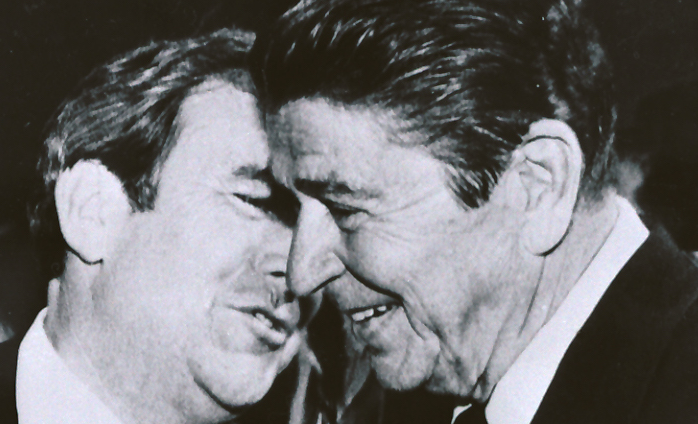

The next speaker was Republican presidential nominee Ronald Reagan, who told the crowd, “I know you can’t endorse me. But…I want you to know that I endorse you.”

This alliance between the Christian Right and the Republican Party has done nothing less than reshape American politics. Here are a few ways it did that.

The Christian Right changed how we talked about race. The Christian Right emerged from school desegregation—and forged a movement around taxes and religious freedom. In 1978, the Internal Revenue Service sought to revoke tax exemptions for schools formed as white-flight havens from the public schools. The backlash was overwhelming. The IRS received more than a quarter of a million letters against the proposed rules. Congressional hearings reframed the issue from an attack on segregation to an attack on religion by meddlesome bureaucrats. As Newt Gingrich, then a freshman representative, explained, “The IRS should collect taxes—not enforce social policy.”

Early in 1979, Jerry Falwell formed Moral Majority, the premier organization for the new Christian Right. Falwell ran a segregated academy that would almost certainly have run afoul of the IRS guidelines. In 1967, the same year the local public schools desegregated, Lynchburg Christian Academy opened its doors. As of the fall of 1979, it had an all-white faculty, and only five African-Americans among the 1,147 students.

In August 1979, Congress inserted riders into the appropriations bill for the Treasury Department to prevent the IRS from implementing the proposed regulations. A fight over desegregation had galvanized white evangelicals to oppose meddlesome bureaucrats, and the movement was born.

It made abortion a partisan issue. The Christian Right made opposition to abortion—which until the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade in 1973 had been a Catholic issue—into an evangelical and Republican cause. The Bible’s text says nothing about abortion per se. Even W. A. Criswell, known as the “Baptist Pope,” initially praised Roe. “It was only after a child was born and had life separate from its mother,” he argued, “that it became an actual person.” Until the mid-1980s, Republicans in the electorate favored fewer restrictions on abortion than did Democrats; in Congress, partisan divides between pro-choice and pro-life votes grew threefold in the two decades after Roe.

The Christian Right found in abortion an issue to bind evangelicals together with conservative Catholics under the Republican banner. Paul Weyrich, a founder of the Heritage Foundation and a deacon in the Eastern Rite Catholic Melkite church, first grasped that a new conservative majority to supplant the teetering New Deal coalition would need white evangelicals—and that opposition to abortion could unite conservative Christians. So Weyrich recruited leading white evangelical ministers to politics, and even coined the term Moral Majority.

As videos of Planned Parenthood discussing the selling of fetal tissue have become flashpoints to shut down the federal government in October, the Christian Right’s legacy still looms large over American politics.

It paved the way for the Tea Party. Since Barry Goldwater’s campaign in 1964, conservative activists have repeatedly overthrown unresponsive Republican organizations and demanded ever-greater ideological purity. The Christian Right provided a useful template for the Tea Party. Just as the Christian Right toppled what a 1980s-era activist termed “Three Martini Episcopalians,” in local Republican parties, the Tea Party has aimed their ire at RINOs (Republicans in Name Only), launching primary attacks against them and making the GOP their own. And just like the Christian Right, grassroots supporters gathered together locally and linked with national-level organizations coordinating across American conservatism.

The Tea Party is not the Christian Right: It does not organize churches or afford a special place for religious communities or their leaders. But it largely shares social conservatives’ goals. White evangelicals make up about 40 percent of Republicans nationally, not to mention a majority of Tea Party identifiers. While the Tea Party has not escaped the central dilemma of the Christian Right, and so many other social movements across American history—how to take a minority viewpoint and make coalitions to forge a national majority – it carries the torch of social conservatism that the Christian Right brought to the Republican Party.

As it turns out, the Christian Right never won the national majority it sought. Instead, social conservatives exercise influence principally inside the confines of Red America. Abortion remains legal—though often inaccessible in conservative states—and school prayer remains illegal. Religious conservatives increasingly emphasize how big government threatens people and communities of faith, whether they are florists who refuse to cut roses for gay weddings or employers who refuse to allow contraceptive coverage for their employees. Christians, Ralph Reed of the Christian Coalition said in 1995, sit at the new “back of the bus.”

Americans have become less Christian and more secular. Around 1990, following a spate of scandals that engulfed leading evangelical pastors, the share of Americans identifying with evangelical denominations began to decline, from its peak at 34 percent to 27 percent. At the same time, public opinion on gay rights started its inexorable shift. New laws and norms around gay rights represent a huge setback for religious conservatives.

The Christian Right has also failed to build permanent institutions. So while it made white evangelicals into Republicans, the preachers and brokers who led the movement now have no role. Direct mail, not billionaires’ checks, sustained the movement, and when the checks stopped, each of the Christian Right’s marquee groups folded.

Without group intermediaries, white evangelicals have failed to build coalitions with other power centers inside the Republican Party and lost influence. Instead, conservative politicians appealed directly to white evangelical voters. Often, they have become niche candidates in presidential elections, winning in caucus states and in the South, but getting nowhere close to nomination. That was the story of Mike Huckabee in 2008 and Rick Santorum in 2012. If Scott Walker, son of an evangelical pastor, breaks that mold in 2016, the Christian Right will finally have elected one of its own as president.

So while there’s no longer a Christian Right with the influence it held in the 1980s and 1990s, without it we’d have a much weaker conservative movement, and a very different Republican Party.

Daniel Schlozman is the author of When Movements Anchor Parties: Electoral Alignments in American History (Princeton: 2015) and a member of the Scholars Strategy Network.

Welcome to the end-game of the Maximal (White) Prosperity Gospel. Donald Trump is the new High Priest. Be wary ye Apostates.

This article is a very good analysis of the history of the evangelical foray into politics beginning in the mid-70’s. I’d be interested in Schlozman’s comments on the rejection of Jimmy Carter by evangelicals, given that he was the most overtly evangelical president we’ve ever had, and whose ascendancy coincided with the rise of the ‘Moral Majority.’

Great article!

Time to give the “Evil Gipper” his due.

He couldn’t win without the extreme, crazy right, so he embraced them. Thirty five years later, after the evils wrought by extreme zealots, trickle down, unnecessary military buildup, rise of the NRA, dismanteling of welfare, expansion of segragation and bigotry, “his and Nancy’s War on Drugs”, hypocrisy of his mismanagement of the government he peached to dismantel, we are left with the ravages to our nation and culture.

America took the wrong turn in the election of 1980. If only we elected the true christian.

Probably that’s covered in his book. I’d imagine it would have to do with Carter’s stand on integration of public schools, and his rather “liberal” stances on separation of church and state.

The net result of the forey of Christians who wear their religion on their sleeve into politics has been that I no longer view my church as a source of training in integrity and honesty. Now it is just another Republican faction; the people who gave George W. Bush 8 years to dismantle my country; and the people who will vote for any dishonest creep who will say the words “against abortion”.

I don’t think I am alone. My home church now looks depopulated and aged, and it’s having trouble paying it’s bills.