We’re asking our fellow TPMers to share their own personal reading recommendations: books they love or that have shaped their lives.

Comment below with some of your favorites! Also, you can always purchase any of the books by visiting our TPM Bookshop profile page.

Associate Editor Nicole Lafond is up this month. Check out her list of five books that inspired her to become a writer.

Being a writer generally sucks.

As is the case with this piece and every other article I’ve released into the toxic abyss that is the internet over the years, nothing a writer writes into existence is ever done, finished, complete or satisfying. There have been a few rare cases over the years – when I’ve covered an issue into the ground or said all I can muster with my sanity still intact – when a piece feels ready to be put to bed. But that feeling tends to evaporate once the “publish” button is deployed and your words in their initial vulnerability are no longer your own, but rather an asset of the collective internet’s holding, ready to be consumed and dissected and criticized and, on good days, mildly appreciated.

That’s why this whole thing called having an editor is really great. I’m an editor and a writer now. My confidence in my abilities while playing both roles is rooted firmly in the fact that there are always two parties (or more) involved, two brains to bounce ideas off of, two vaults of vocabulary to draw from, two guts to check before the work feels final.

My first experience with an editor was a humbling one. I joined my school newspaper as a junior in high school. The first story I ever wrote was centered on something fluffy: the school district’s new contract with some green-ish food service for school lunch. I was utterly devastated by the edits.

In my first attempt to do A Journalism, I found that what I once thought was unadulterated eloquence was, in fact, far too presumptuous for a reported piece and painfully verbose. I wasn’t getting to the point. I was stretching facts. The intro of the story – which I eventually learned was called a “lede;” a nauseatingly rigid form of sentence structuring that not only has its own scientific formula for success, but also requires a great deal of humility to craft correctly – was meandering and basic. There were no transitions. Confidence shattered, I dug into the notes with my editor, who was the high school newspaper adviser at the time. He pulled out an outdated AP Stylebook and we tore my piece apart some more together.

Crafting, dismantling, reconstructing and rewriting, we learn to carry on in this career. It’s the sole safeguard against your own brain in this industry. While a piece may not read quite like an excerpt of the Dead Sea Scrolls when it’s time to publish, there’s comfort in knowing multiple parties found the work to be solid and complete before it went live. (Editors Note from me: Stand steady in the knowledge that this feeling I’m describing is a hyperbolic articulation of Nicole S. Lafond Mania – a form of inner, self-induced torture and one that is in no way a reflection of the rigid fact checking and rigorous obsession that goes into writing, editing and publishing a reported piece for TPM).

But there’s a strange dichotomy here that, I think, most writers find themselves forever straddling – a religious truth for those of us who, for god knows what reason, have chosen to (reluctantly) accept that this writing thing that we do is, in fact, the thing that we do. My work may forever feel unfinished. But everyone else’s is scripture, written into our collective consciousness by a being of higher authority who had been chosen to drop the inspired words of a deity onto a page.

It’s no secret that reading a lot, especially at a young age, encourages the development of whatever brain neuron pathways need to be connected and nourished in order for someone to not only make the maddening decision to want to be a writer, but to be a decent one at that. And literary icons who speak to us most do a lot of work to keep us humble, keep us inspired, but mostly, to keep us going.

So, let’s start at the beginning.

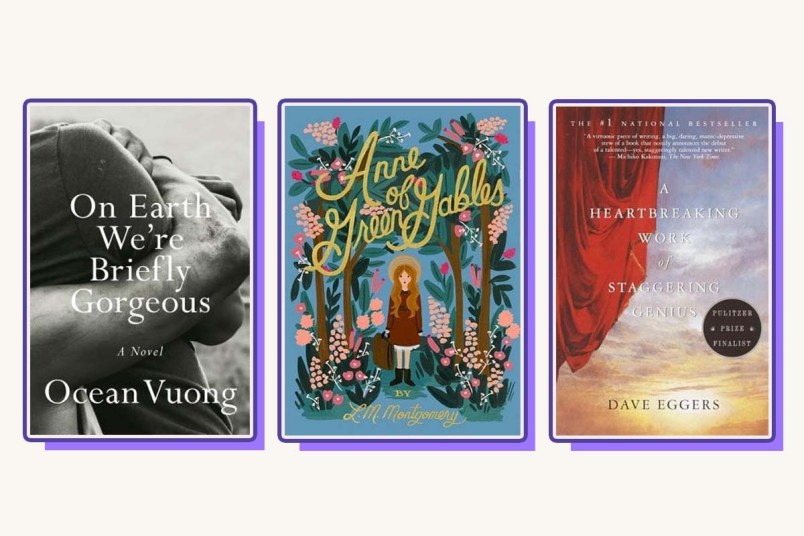

Lucy Maud Montgomery’s ‘Anne of Green Gables’

I only recently learned that L.M. Montgomery purposefully went by her initials in order to conceal her gender. At the time, Montgomery was a pioneer, writing about the female experience and cementing Anne Shirley’s status as an iconic literary character during a time when stories about and for women depicted little beyond the sexist tropes that still plague depictions of the femme experience to this day. Anne is the encapsulation of a young woman who unapologetically takes up too much space, loudly dismantling the peace of the set-in-their-ways adults and kindred spirits she meets throughout her enchanting Green Gables journey.

And Montgomery articulated her import beautifully, waxing eloquent about her flaws, immortalizing her physical shortcomings as poetry. While perhaps a bit flourished linguistically, Montgomery has a knack for saying a lot in order to say a lot. She vocalized it most iconically here:

It has always seemed to me, ever since early childhood, amid all the commonplaces of life, I was very near to a kingdom of ideal beauty. Between it and me hung only a thin veil. I could never draw it quite aside, but sometimes a wind fluttered it and I caught a glimpse of the enchanting realms beyond — only a glimpse — but those glimpses have always made life worthwhile.

Kate Chopin’s ‘The Awakening‘

While Montgomery’s work may be an over-the-top venture in romanticism, Chopin’s writing is a brusque companion. With biting precision in her brevity, Chopin darkly illustrates the nihilistic repercussions of romanticizing reality. The combination of the two taught me the value in both winding prose and sharp descriptors. Sentence length variation! A seemingly simple concept, but one that adds unparalleled complexity to the written word.

“The bird that would soar above the level plain of tradition and prejudice must have strong wings. It is a sad spectacle to see the weaklings bruised, exhausted, fluttering back to earth.”

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s ‘Le Petit Prince‘

I read this philosophical children’s book for the first time in French – in my high school French 3 Honors class to be exact (shoutout to, you, Madame Dueppen). It was one of those fundamental aggravating experiences anyone learning a second or third or fourth language goes through at some point, recognizing the value in the untranslatable, in the je ne sais quoi. But for the purposes of this post, “The Little Prince” exposed me to a quality in good writing that holds fundamental weight in journalism: The art of articulating a perspective outside of your own. Saint-Exupéry does this masterfully – conveying philosophical lessons about the pillars of humanity through a child’s eyes.

“And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

Dave Eggers’ ‘A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius‘

These last two books have influenced me on a mental health level that I am always clamoring to discuss, so if you’re a fan, please shoot me an email. On a literary level, Eggers has a stream of conscious gift that even Jack Kerouac would admit the Beats couldn’t quite see to fruition. And he’s funny, like rib-cracking, LOL-ing in the face of doom, funny. Eggers taught me to not take my writing (or myself, for that matter) so seriously – that sometimes just dumping everything onto the page as a starting point, and revising, or not revising, later is just as key to bringing a story to life as the art of thoughtful clarity.

“I straighten the rug in the hall. I find the broom and sweep. I open the refrigerator and throw away a heavy bag of blue oranges. And baby carrots, now brown and soft. I go to my room, open the blinds. Across the street, at the retirement home, an elderly woman is out on the porch, moving slowly, watering her plants. I go back to the kitchen and pick up the phone. Who to call? I put it down. I turn on the computer. Get up, turn on the oven. What to cook? We have no food. I sit down, look at the computer and turn it off and stand up, staring toward the door. I lean my head against the molding near the window. What if my head became attached to the wall? I could be half of a pair of Siamese twins, attached at the head, the other half was actually this wall. I could be half man, half wall. Would I die if not separated? No, I could survive.”

This passage conveys just as much about the human experience as “Jesus wept.”

Ocean Vuong’s ‘On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous‘

Vuong’s writing is unmatched in modern American literature. He spills prose on a page like it’s an accident, all while embodying with ease the kind of prolific thinking that earns one the distinction of being the voice of an entire generation. I’m a fan if you can’t tell and his gift extends deeper and wider than what I will say here. While not necessarily a journalistic writer, “On Earth” is a memoir, Vuong’s work is a masterclass in the subtle depth of good dialogue; the power of a pointed quote.

“What were you before you met me?”

“I think I was drowning”

“And what are you now?”

“Water”