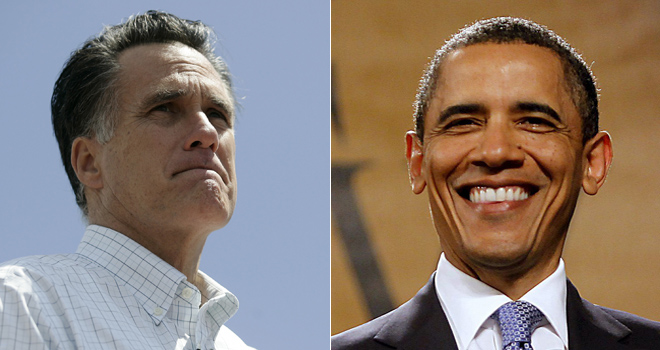

It took tens of millions of dollars, years of preparation and three months of primary contests, but Mitt Romney is finally the GOP’s presumptive nominee. Now comes the hard part.

Romney’s first day of the general election turned into a stark reminder that Obama will be a far tougher opponent than the poorly funded, disorganized candidates he battled in the primary. Romney was outmaneuvered and forced off message throughout the day — beginning with a morning press call in which the campaign was caught flat-footed over a simple question about Romney’s position on the Lilly Ledbetter Act — overshadowing the economic message he was trying to push, with the gleeful help of an armada of professional Democratic operatives.

The new Republican standard-bearer began the morning on FOX News on the defensive, pushing back against Democrats’ claim of a Republican “war on women” by blaming Obama for slow job growth among women.

“His polices have been really a war on women,” Romney said. “Over 92 percent of the jobs lost under this president were lost by women.”

The move was a classic example of what has become a consistent Romney maneuver: projecting his own vulnerabilities onto his opponent, in this case his toxic polling with women voters. But Romney’s move quickly revealed the dangers of playing on your opponent’s territory.

A group of Romney advisers held a conference call immediately after the Fox News interview in which they repeated Romney’s “92 percent” claim and lamented the “enormous damage” done to women under Obama. But when three reporters asked the logical follow up — why are there fewer jobs for men in recent months and what would Romney do to fix the gender gap in hiring? — they were unable to offer any explanation. Another obvious follow-up question, “Does Romney support the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, which makes it easier for women to sue over pay discrimination and was Obama’s first signed law?” generated only a long, awkward pause before an aide finally responded: “We’ll get back to you on that.”

The Democratic machine sprang into action. Operatives jumped on the Ledbetter line, sending it out to supporters and media and urging Romney to detail his position. Before Romney’s campaign could even clarify, the Obama campaign had already produced a lengthy statement from Ledbetter herself, describing how “shocked and disappointed” she was by the ambiguity. Democrats had also distributed a copy of the audio from the Romney camp’s phone call.

The Romney campaign, which was trying to shift the discussion to its preferred topic of jobs, instead was forced to backpedal on equal pay, an issue on which the GOP is on much shakier ground with women voters. A spokeswoman for the Romney campaign told TPM he supported “pay equity” but as for the bill itself, she’d only say that the candidate is “not looking to change current law.”

That put Romney on the other side of the overwhelming majority of Republican lawmakers, who almost unanimously opposed the bill’s passage in 2009.

National and state Democrats sent out dozens of press releases on Ledbetter within hours.

“For the president, equal pay for equal work has always been a no- brainer,” DNC Chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz said in a conference call with bloggers. “Meanwhile on a question that shouldn’t have required a millisecond of hesitation, Mitt Romney’s aides responded with a deafening six-second silence followed by, ‘We’ll get back to you on that.'”

By then, the Romney campaign was firmly on defense, issuing statements from female supporters attesting to Romney’s commitment to “pay equity” and repeating the party line that Obama’s economic policies are worse for women. Democratic operatives, again with lightning speed, instantly noted that two such statements came from congresswomen who

voted against the Ledbetter law, Reps. Cathy McMorris Rodgers and Mary Bono Mack.

Meanwhile, Romney’s “92 percent” statistic was also taking a beating. The Romney camp ended the day struggling to defend the number which, while technically accurate, was almost universally judged misleading by independent analysis, as there were clear economic reasons behind the gender gap that had nothing to do with Obama, and, again, Romney offered no coherent explanation as to why the disparity existed or how he would change the ratio himself. By the late afternoon, Romney’s aides were publicly demanding that Politifact — hardly the only outlet to criticize the claim — retract its article judging the line “mostly false,” wading into a distracting process fight rather than touting the jobs message they’d planned to champion all day. Politifact agreed to a review, but noted correctly that many outlets reached the same conclusion, including the Washington Post and AP.

The closest Romney came to regaining footing was launching an all-out grievance war Wednesday night on a Democratic pundit who appeared on CNN. Hillary Rosen, who has no connection to the Obama campaign, awkwardly suggested Ann Romney can’t fully understand working mothers because she “never worked a day in her life.” Ann Romney herself joined Twitter just to respond, which helped give the story legs and at least forced actual Obama aides like David Axelrod and Jim Messina off the sideline to quickly condemn the remark.

As difficult a time Romney had overcoming a parade of challengers to take the GOP nomination, the episode underscored just how much tougher the general election will be. Democrats have built a finely tuned — and loud — messaging and research operation. And Romney, for the first time in more than five years, had to navigate an electorate that included more than just base Republicans, abandoning his party’s near-unanimous stance on a pay-equity bill in order to avoid doing even more damage to his already anemic share of women voters. His opponents have more cash than him for now to boot, a situation completely alien to Romney, who outspent his nearest primary competitor at 5:1 clip.

Twenty-four hours after Santorum’s exit, the scoreboard shows Obama 1, Romney 0.